Jean Moran (1898-1971) was a successful restaurateur who ran several eateries in Washington from the World War II years until she retired in 1965. Born Lillian Jean Conery in New Orleans, Louisiana, she favored atmospheric eateries with multiple, separately themed rooms. Eating at one of Moran’s restaurants was an immersive experience designed to uplift the spirit as much as satisfy the palate.

|

| Postcard of the Stables Restaurant (author's collection). |

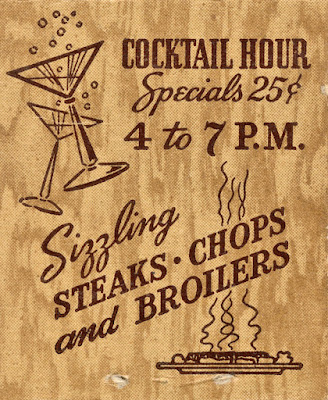

One of Moran’s first ventures was a converted former horse stables at 2620 E Street NW in Foggy Bottom, known simply as The Stables. Before the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts was built, several stables and horse-riding academies had buildings in that area. Moran—known as Jean Richards at the time—opened The Stables sometime in the early 1940s. During World War II, when gas rationing limited automobile use, she faced a disadvantage in that her quaint and charming inn was out of the way for most downtown visitors. She responded by outfitting an elegant Victorian-era coach drawn by a pair of bay horses to serve as an evening-hours shuttle between downtown hotels and her restaurant. The coach rides generated great publicity and added to the restaurant’s charm.

|

| Stables Restaurant matchbook cover (author's collection). |

Overcoming one wartime restriction did not address others, however. Moran was beleaguered by rationing restrictions. In 1943, the same year she married Barney Moran, her restaurant was barred by the Office of Price Administration from purchasing meats, fats or cheese until its overdrawn rationing account was balanced. Moran sought a “loan” of ration points to keep her in business until her account was balanced but was refused. She wrote a letter to the agency accusing it of “Gestapo methods.” “Thanks to your dictatorial attitude,” she wrote, “from a thriving, healthy, successful enterprise my business has deteriorated into sickliness.” If this didn’t satisfy the OPA, she suggested, “the Potomac is only a few feet away and it should be a simple matter…for you to shove me into the river and drown me.” The hardball tactic worked; the OPA reversed course and granted her the loan of ration points.

Nevertheless, her troubles were not over. In 1945, the OPA raided the restaurant, arrested Moran, and seized meat and cheese. Moran said it was “just like a kidnapping.” The OPA agents “just swooped into my kitchen without showing any badges or credentials whatever.” Finally, in 1949 the government shut the place down for failure to pay taxes. Moran protested the seizure in a telegram to President Truman, but to no avail. Furnishings were auctioned off, and the building was leased to Howard Johnson’s, which used it as a supply depot.

|

| Old New Orleans matchbook cover (author's collection). |

Despite the loss of The Stables, Moran had another venture underway. In September 1940, she opened the Old New Orleans restaurant at 1404 18th Street NW. Within a year, the eatery moved to 1214 Connecticut Ave NW, south of Dupont Circle, where it would remain for more than a decade. The Old New Orleans was Moran’s homage to her hometown, featuring separate Hunt, Latin Quarter, and Continental rooms. Psychic Roberta Robbins was on hand to tell your fortune during evening entertainment, and on the third floor the orchestra played dance music at the Chateau Internationale. While Moran soon moved on to other ventures, the Old New Orleans remained for many years a well-known nightspot, featuring top drawer entertainment, including French singer Hélène François.

|

| Old New Orleans postcard (author's collection). |

|

| Singer Hélène François pictured on an Old New Orleans postcard (author's collection). |

In 1955, Moran took over the former Wise Funeral Home at 2900 M Street NW in Georgetown and turned into the ultra-chic L’Espionage restaurant, a full year before the Rive Gauche opened. Restaurants like L’Espionage and Rive Gauche marked the arrival of a new era of fine French dining in Washington and established Georgetown as a dining destination for the first time in the modern era. L’Espionage featured four separate rooms seating about 40 each. The Diplomacy Room, decorated in rich red velvet, and the Intrigue Room, in black and white, were on the ground floor. Above was the Attic, said to have a Charles Addams look, and in the basement was the Underground, where one could dine by candlelight in an old brick cellar and pretend to be a James Bond character. Moran told the Washington Post she came up with the room names “because local papers feature so much cloak-and-dagger stuff.”

|

| L'Espionage matchbook cover (author's collection). |

By 1964, the Evening Star’s dining critic John Rosson was able to say, “L’Espionage has always been looked upon as one of THE places to go. Both the food and the décor—to say nothing of the Parisian air—place it high on many lists.” The occasion of Rosson’s column was the sale of the restaurant to another veteran D.C. restaurateur, Gusti Buttinelli, who promptly lowered some of the eatery’s steep prices. The gambit apparently didn’t work; he closed the restaurant about a year later.

|

| Pages from a L'Espionage menu (author's collection). |

Meanwhile, Jean Moran had started another dining spot across the street at 2915 M Street. Opened in 1961, the Rue Royale once again harkened back to Moran’s beloved New Orleans. Said critic Rosson, “The Rue Royale, as tasteful a display of regal New Orleans as we’ve ever seen, can be described in two words: ultra elegant. You know you’re dining out. It’s an occasion. You’re dining in splendor.” Smaller than L’Espionage, Rue Royale sat 90 in three rooms. First was the Shell, a barroom decked out in black leather, dark walnut paneling, and hung with gold-framed portraits of old Louisiana families. Second was the main dining room, called the Chartreuse Room, and finally the Larder, a clubroom intended primarily for men. The menu had just four choices, each a complete meal, including ice cream for dessert.

|

| Rue Royale matchbook cover (author's collection). |

Jean Moran retired from the restaurant business in 1965, when the Rue Royale closed. She died from a heart attack six years later, at age 73.

Comments

Post a Comment