The short, exuberant life of Washington's Café République

The restaurant business is famously risky, and perhaps the greatest risks are taken by those who invest in elaborate new eateries without a sound plan for making them profitable. Such is the cautionary tale of the posh Café République, an extravagant enterprise that flourished for just a few years in downtown Washington in the 1910s, serving as a quintessential expression of the fragile exuberance of its times.

In April 1910, a group of local investors organized as the Columbia Cafe Company to open the Café République in remodeled space at the northwest corner of the Corcoran Office Building, located at 15th and F Streets NW, across the street from the Treasury Department. After a whirlwind construction effort, the new eatery was ready to open its doors in late September.

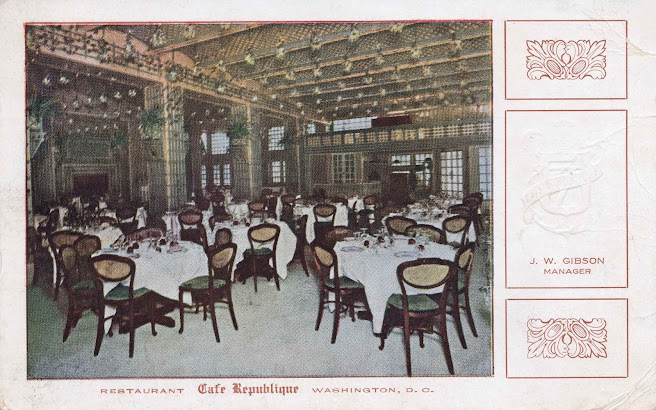

Architects Oscar G. Vogt and Milton Dana Morrill, whose offices were in the Corcoran Building, traveled to France to inspect the finest French restaurants, then to New York and Philadelphia to see the best that America could do, before developing their ne plus ultra design. The result was lots of ferns and frills, an over-the-top Edwardian fantasy garden. An elaborate fountain with goldfish and aquatic plants stood in the center of the dining room, which was festooned with vines and hanging lights. In addition to the main dining room, there was a “sanitary” lunchroom, with burnished copper gleaming throughout the kitchen and a seating area with walls “enameled to the whiteness of alabaster” that could be flushed out with a hose. Downstairs in the basement was a Flemish-inspired rathskeller with heavy oak wainscoting and rustic tile walls.

|

| Advertisement from the September 29, 1910 edition of The Washington Times. |

Public announcements stressed the cafe's up-to-the-minute amenities, including telephones at every table and wires for electric chafing dish attachments. Dozens of electric fans, hundreds of electric lights, and a wide variety of electric kitchen equipment marked the café as the embodiment of cutting-edge technology. For the business-minded lunchtime crowd, the rathskeller was equipped with a stock ticker and, of course, all the latest newspapers from Washington and other cities.

“At last Washington is to possess a truly great café—a café which, in the magnitude of its proportions, the elegance of its furnishings, and the completeness of its equipment, will express adequately the ideals demanded by a large and growing cosmopolitan community,” exclaimed the Washington Post in a full-page feature that raved about the trendy new restaurant. “Many a social conquest and many a political coup will be planned by society leaders, statesmen, and diplomats over the little round tables of the Café République,” it continued. Noting that the café was an entirely local enterprise, the Post concluded that “it must be the wish of every progressive, public-spirited Washingtonian that the success of the Café République be at once decisive and instantaneous.”

Though its appointments were marketed as the height of luxury, the café was in fact meant to be broadly appealing. The café’s expensive-sounding “truffles, paté de foie gras, and baked ice cream” were all available at “reasonable” prices, management insisted. The restaurant business, which heretofore had catered primarily to wealthy white men, was poised for sea change as the increasingly prosperous middle classes sought diversions outside of their homes and large numbers of women began patronizing eateries on the own. Young couples out on dates needed a place to dine that was suitably elegant and yet at the same time affordable. The Café République's owners aimed to draw in large numbers of these customers.

|

| This advertisement appeared in a 1912 DC theater playbill (author's collection). |

Patrons indeed thronged to the new café on its opening night, with every table taken from 8pm to midnight and many potential customers turned away. A year later, adjoining space in the Corcoran Building was leased allowing the addition of a new tearoom off the main dining room. Another grand opening was held for the new space in September 1911, with music by a Hungarian orchestra and American Beauty roses given to each female customer.

Then, in August 1912, the house of cards began to collapse. The restaurant had not been paying its bills. Several of the café’s many unpaid creditors, including the American Ice Company, the Frazee-Potomac Laundry Company, and the Arlington Bottling Company, forced the café into bankruptcy and receivership. The Columbia Cafe Company was found to have over $122,000 in debts and just $41,178 in assets. The receivers at first were instructed to keep the café running, but they soon found that it was "a hopeless task to make the fashionable restaurant pay," as the Post reported. On the last day before it was shut down, "many handsomely gowned women and their escorts sat round the small tables eating with a degree of unconcern, while the stoic expression of the white-aproned waiters would never have revealed the fact that the pantry shelves were practically bare." After the food was gone, trustees auctioned off all the restaurant's fixtures and furnishings.

But the Café République was not a historical footnote quite yet. Joel Hillman, a successful hotelier who ran Harvey’s Oyster House, purchased most of fixtures and used them to reopen the café in October 1912, shortly after it had closed. The restaurant continued in much the same vein as before. A January 1913 advertisement offered lunches at 40 to 50 cents, a very moderate price. Entertainment was provided by the Ladies' Viennese Orchestra. Apparently this wasn't enough to turn the tide of profitability. By April, the cafe was closed again, its fixtures put back on the auction block. This time there would be no reopening.

|

| 1914 postcard of the Jardin de Danse (author's collection). |

The vacated space at the base of the Corcoran building would never have another long-term tenant. Instead it was leased for a succession of short-lived purposes. After the great success of the Women's Suffrage Parade in March 1913, suffragists used the former cafe space for a five-day demonstration kitchen to show off their cooking skills, for example. Then, in October 1914, Miss Bertha King, "one of this country's recognized authorities on dancing," according to the Post, opened the Jardin de Danse in the still elaborately decorated dining hall. In addition to dance lessons, the studio offered light lunch and evening fare, and it was apparently also rented out for charitable events. Soon after it opened, the District Federation of Women's Clubs held a fundraiser in the space to assist the Red Cross on the European battlefields of World War I. In December another charitable event to collect donations for Belgians ravaged by the war was held here. Bu the Jardin de Danse doesn't seem to have lasted past 1915. In 1916, another charitable drive to support Emergency Hospital was headquartered out of the space, which this time the Post described as "the big room on the first floor of the Corcoran building, which since it ceased to be the Cafe Republique...has had a gloomy existence."

|

| This is what the corner of 15th and F looks like today. The Hotel W looms where socialites once gathered at the Café République (photo by the author). |

All the while, negotiations had been underway to sell the Corcoran Building, which William Wilson Corcoran had constructed in 1875 and which had been famous in its heyday for its many artist studios, and were soon concluded. In early 1917 the building was torn down to make way for the new Hotel Washington. Even if the Café République had somehow managed to survive that long, and even if the Corcoran Building hadn't been demolished, the restaurant probably would have closed soon anyway. In November 1917 Prohibition came to the District, the ban on alcohol sales dealing a death blow to many of the city's long-established restaurants. With a world war and a pandemic also close on the horizon, life would never be the same.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included James M. Goode, Capital Losses, 2nd ed. (2003); Andrew P. Haley, Turning The Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920 (2011); Michael Lesy and Lisa Stoffer, Repast: Dining Out at the Dawn of the New American Century, 1900-1910 (2013); and numerous newspaper articles.

Comments

Post a Comment