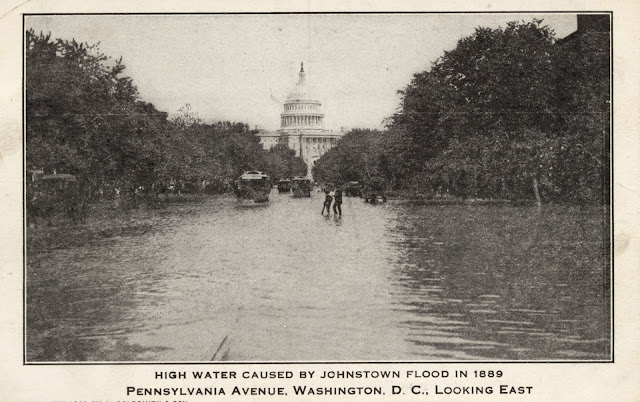

The Great Flood of 1889 in D.C.

A massive storm system lumbered up the eastern United States from the Gulf of Mexico at the end of May 1889, dumping extraordinary amounts of rain everywhere it went. As it hammered the mountainous region of western Pennsylvania, the sheer quantity of water overwhelmed a poorly maintained dam, causing it to fail and send millions of gallons of water roaring down a narrow valley to destroy Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Over 2,000 lives were lost. While Washington fared far better than Johnstown, the flood of the Potomac river was still the worst the nation's capital had ever seen. A total of 4.4 inches of rain fell, and at the peak of the flood parts of Pennsylvania Avenue were covered with from 1 to 4 feet of water.

|

| A souvenir postcard of the flood, issued on its 20th anniversary in 1909 (author's collection). |

The disaster at Johnstown happened on May 31, the second of two days of drenching rain. As usually happens, riverine floods in Washington come about a day after heavy rains, because it takes time for the runoff to fill the Potomac and arrive downriver at Washington. In this case, the floodwaters came on June 1 and June 2, when the Potomac crested at a full 12.5 feet above flood stage.

|

| A widely-circulated stereoview of the wreckage of the Johnstown flood in Pennsylvania. The "dead body" in the foreground is an actor lying in the wreckage for dramatic effect (author's collection). |

Down on the Georgetown waterfront, the water began overflowing its banks around 10:30 on Friday night, imperiling the commercial wharves. Workmen frantically tried to remove stacks of wood from the Wheatley Brothers lumberyard, knowing much of the lumber would probably be swept downriver. Nearby Libbey & Bro. would lose $2,000 worth of Florida pine from its wharf. The Independent Ice Company loaded ice on dozens of wagons to be hauled to higher ground but would later lose an entire frame storehouse containing 1,500 tons of ice. Workers at Cissel's flour mill carted away as many barrels of flour as they could. As Saturday wore on, the Potomac continued to rise. Several thousand tons of coal that had been in tall heaps on the H.C. Winship wharf were swept into the river.

Spectators crowded the railings of the Aqueduct Bridge to marvel at the mighty river as it steadily rose and grew in power. "The water swirled and swung under the Aqueduct bridge, boiling as it struck the piers, and whipping up a foam with a roaring and grinding sound that was frightful," the Star reported. Several large boats on the C&O Canal in Georgetown rammed themselves against the bridge that carried K Street over the creek and shattered to pieces. Boathouses flooded, their ground floors disappearing under the water.

|

| (Author's collection). |

The flooding spread Saturday night not only on the Georgetown waterfront but along Pennsylvania Avenue, Potomac Park, the C&O Canal, and even at the Navy Yard, along the Anacostia. The Potomac was "a wide, roaring, turbulent stream of dirty water," carrying logs, telegraph poles, and all kinds of debris. Rail lines were cut off, both to the north, where the route to Baltimore was partially washed out, and to the south, where the Long Bridge was battered and broken but still standing. The boathouse of the Analostan Boat Club, located just south of Rock Creek in Foggy Bottom, was swept off its foundation Saturday night and carried out to sea in pieces. The southwest waterfront, home to many commercial wharves and steamboat docks, was completely submerged. "The ruin wrought is at present time incalculable," the Post observed.

The most vulnerable part of the city to flooding was the area between Pennsylvania Avenue and B Street NW (now Constitution Avenue), where the Washington City Canal once flowed (The canal had been filled in, and the stream that fed it, Tiber Creek, had been turned into a large sewer). The flood swiftly re-established the waterway. "It looked like ante bellum days on B street," noted the Post, "but instead of a sluggish, ill-smelling canal, as in the sixties, there was a rapid stream..."

|

| Photo appearing in Willis Fletcher Johnson, History of the Johnstown Flood (1889). |

In the heart of this flood zone stood the great Center Market, flanked by several blocks of merchants' warehouses, stocked full of groceries and other goods, many of which were stored in basements. Dozens of workers had spent Saturday hauling goods from cellars up to higher floors as the water slowly rose. "Fluttering chickens, scared calves, and bleating lambs" were hurried away to safety. Some stores, like that of merchant James S. Barbour, were kept temporarily clear by pumps that ran all day Saturday, but inevitably they were engulfed in the rising flood. By Sunday morning, cellars were submerged throughout the area, water covering the street to the depth of a foot or more. Center Market itself was inundated, forcing an "army of rats" to frantically flee their homes beneath the market stands. A large turtle that would have been turned into soup escaped into the broad open water and was never seen again.

|

| The Baltimore & Potomac station is in the rear in this view; the Howard House Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue is in the foreground (Source: Library of Congress). |

The ornate Baltimore & Potomac railroad station, its train sheds extending out on to the Mall, stood in more than a foot of water. Anxious passengers, hoping against hope that they could board trains out of town, were forced to face reality and retreat from the raised steps of the station on Saturday afternoon. Trains stood immobilized in water. Sometime on Saturday, the United States Fish Commission's large ponds near the Washington Monument quietly merged with the floodwaters, dispersing many thousands of fish. One large German carp was caught on Pennsylvania Avenue, while another was found swimming inside the ladies' waiting room of the Baltimore & Potomac station.

|

| View of 6th Street crossing the mall, wit the B&P train station on the left. A train can be seen under the shed at the rear of the station. (Source: DC Public Library David Sterman Collection, with assistance of Ryan Shepard). |

On Pennsylvania Avenue, bubbling whirlpools at street corners were the only signs of submerged sewer holes. Several nimble entrepreneurs managed to get hold of small boats and provide ferry service across the avenue, charging five cents a ride. Others offered carriage rides, where the water was not too high for horses to navigate. An African American man carried stranded guests on his shoulders to the St. James Hotel. Several times he fell, dumping his passengers in the water with a great splash and drawing laughter from spectators. Meanwhile, the Belt Line's horse-drawn streetcars remained in service, despite the water reaching almost to the floor of the cars.

|

| (Author's collection). |

Around 3 pm on Sunday the water began slowly receding. The weather had cleared, and to many well-to-do Washingtonians, the natural disaster was a source of great entertainment. Spectators crowded not only Aqueduct Bridge and other outlooks in Georgetown but also the edges of the flooded parts of Pennsylvania Avenue, marveling at the sight of the new Venice on the Potomac. The streetcar companies did "an enormous business," every car being "packed to its utmost capacity." Families picnicked on Observatory Hill in Foggy Bottom, which offered a panoramic view of the water. Georgetown saw 50,000 visitors, and "there was a continuous stream of carriages going up to the Chain Bridge all day long," according to the Post. (To the south, Long Bridge, still standing but heavily damaged, was barricaded to keep spectators away.) Even President Benjamin Harrison and First Lady Caroline Scott Harrison got in on the fun, observing the flood from the library of the White House with the aid of a telescope obligingly provided by the U.S. Lighthouse Board.

Others were not so fortunate, especially those who lived in low-lying areas near the Georgetown waterfront or in Southwest, where many African American families had their homes. "A number of families, especially of the poorer classes, have lost nearly everything, and to them the hardships are doubly great," the Post observed. "The history of the misery and ruin wrought by the rushing waters can never be told." As the floodwaters rose on Saturday night, Southwesters still at home were awoken by the sound of water and debris sloshing at their doorsteps; they were forced to flee at once, leaving all their possessions behind. Similarly, African American families living in small frame "shanties" on B Street (Constitution Avenue) were driven from their homes during the night. The full story of their losses has indeed never been told.

Loss of life, thankfully, was small, despite rumors to the contrary. The first reported fatality was that of Charles Sparshaw, a maintenance worker for the Washington & Georgetown streetcar company, who lived in Rosslyn and was down by the river on the Virginia side attempting to salvage lumber from the floodwaters when he slipped and was washed out to sea.

As early as Sunday afternoon, Washingtonians started cleaning up the mess that was left behind. Fear of disease drove the rapid response. Workers labored all Sunday night to clean out Center Market, which proudly opened for business as usual on Monday. The city's street cleaners likewise had Pennsylvania Avenue clear in short order.

|

| Excerpt from a map showing the extent of flooding (outlined in blue) from the 1889 flood. (Source: Library of Congress). |

Longer term issues remained, however. Flooding of the area south of the White House had grown more and more frequent since the Civil War, due to extensive deforestation upriver and the resulting silting of the river. Great marshy flats had developed that were feared to be a source of malaria. Beginning in 1882, the Army Corps of Engineers had been working to dredge deeper channels in the flats and build up the dredged material into new dry land, called Potomac Park, that was protected by stone seawalls. While the Army's efforts were set back by the flood of 1889, work continued under Major Peter Hains. After the project was completed in the 1890s, flooding was less common.

Georgetown's commercial waterfront had been bustling before the flood of 1889, but it would never recover. The devastation along Water Street, with the pungent remains of fertilizer, coal, and timber strewn about, was profound. Most important, the C&O Canal, which supplied Georgetown with raw materials like grain, coal, and timber, had been wrecked. Along the Palisades stretch above Georgetown, there were gaping holes where the canal's earthen walls had stood. The day after the flood, Maryland Senator Arthur P. Gorman told the newspapers that he doubted the canal would ever reopen. In fact, it took two years to get the waterway back in operation, by which time much of its traffic had been diverted to other destinations via the B&O Railroad.

The silting of the Potomac at Georgetown had been a growing problem throughout the 19th century, and the various floods of the 1870s and 1880s only accelerated the process. Technology was also leaving the old commercial port behind. Modern, steam-powered gristmills in the midwest were producing higher-grade flour at a lower cost than Georgetown's old-fashioned waterwheel-driven mills, which depended on the canal for power. Georgetown was already being called "West Washignton," reflecting its gradual change from a once-thriving, independent port to less-prominent, residential section of the larger capital city.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included: Kevin Ambrose, Dan Henry, and Andy Weiss, Washington Weather (2002); Willis Fletcher Johnson, History of the Johnstown Flood (1889); David McCullough, The Johnstown Flood (1968); National Capital Planning Commission, Report on Flooding and Stormwater in Washington, DC (2008); Pamela Scott, Capital Engineers: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in the Development of Washington, D.C. 1790-2004 (2005); Kathryn Schneider Smith, Port Town to Urban Neighborhood: The Georgetown Waterfront of Washington, D.C. 1880-1920 (1989), and numerous newspaper articles.

Great article!

ReplyDelete