Back when Union Station was the primary gateway to the city, the blocks nearby were filled with moderately priced hotels catering to the thousands of travelers and tourists disgorged by arriving trains. One of the earliest and longest standing of these was the Hotel Continental at 420 North Capitol Street NW near E Street NW, about a block away from Union Station and equidistant to the Capitol.

|

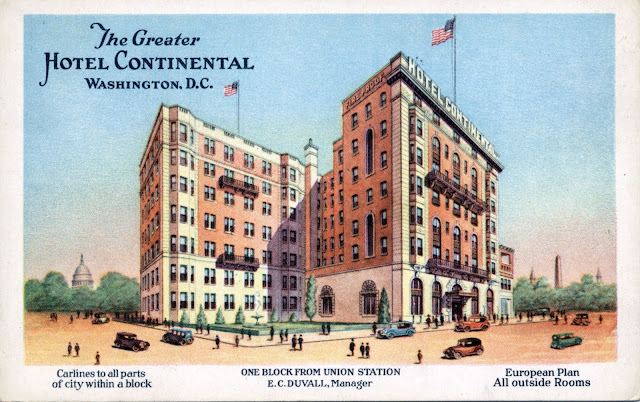

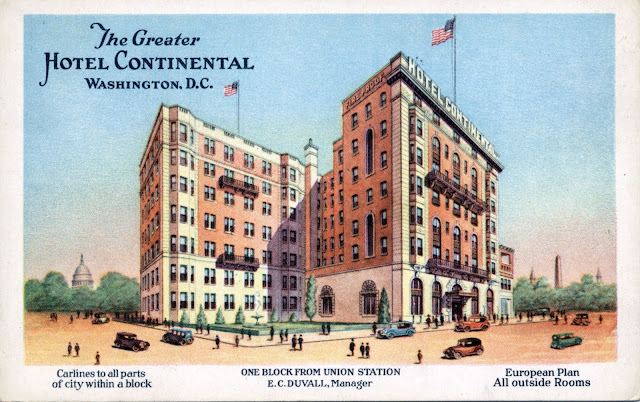

| 1930s postcard from the Hotel Continental (author's collection). |

The completion of Union Station in 1907 marked an important shift in Washington's hotel business. Trains previously arrived at two different stations at other locations: the Baltimore and Potomac station, which serviced Pennsylvania Railroad trains, was on the Mall at present-day Constitution Avenue and 6th Street NW, where the National Gallery of Art now stands. Several hotels clustered in the immediate vicinity, including the

National, the

Metropolitan, the

St. James, and others. Trains from the competing Baltimore and Ohio Railroad arrived at a station on New Jersey Avenue NW, several blocks southwest of where Union Station was later built. That area had its hotels as well, but it had become run down by the early 20th century, when many of the buildings in the neighborhood were razed.

That left the neighborhood to the north, around Union Station, as a ripe location for new hotels, and at least half a dozen were built in the 1910s and 1920s. Completed in 1911, the Continental, was designed by Appleton P. Clark, Jr. (1865-1955), the dean of Washington architects, who designed many schools, churches and other public buildings as well as apartment houses and private homes. Clark was a prominent DC businessman and real estate investor who chaired the Board of Directors of the Washington Hotel Company, the developers of the Continental. One can easily imagine Clark and his board meeting sometime shortly after Union Station's completion to plan their lucrative new hotel.

|

| Appleton P. Clark, Jr. (Washington Past and Present, 1930) |

Clark designed an elegant, moderately-sized hotel of seven stories and 150 rooms. The ornate Beaux-Arts style was fashionable at the time and in keeping with the style of other large public buildings in the city. The building was constructed as a steel-frame structure dressed in beige pressed brick and Indiana limestone with terracotta trim. Interior finishes were of marble, tile, and hardwoods, and the tiled bathrooms—one for every suite—were equipped with plumbing fixtures "of the best quality." Guest rooms were fully carpeted, with brass beds and mahogany furniture. Spacious lobbies dominated the first and mezzanine floors, where dining rooms, ladies' parlors, and writing rooms were also available. In the basement were an Old Dutch-style grill room, buffet, barber shop, and billiard room. The rooftop featured a garden for taking in the striking views of the nearby Capitol as well as the rest of the city skyline. The Washington Hotel Company characterized the Continental as a "first class hotel where rooms and service can be procured at reasonable rates."

|

| An early postcard from the hotel (author's collection). |

|

| The first-floor cafe (author's collection). |

|

| The mezzanine (author's collection). |

When it opened in March 1911, the Continental was the first to appear in the Union Station area. "Visitors to the Capital who arrive at Union Station after sundown will no longer be confronted by a screen of darkness, broken only by the weird illumination of the Government Printing Office, for across the great plaza can now be seen an inviting edifice, shedding a glow of light from its many windows, suggestive of hospitality and luxurious comfort," wrote The Washington Herald. The previous day, the newspaper's reporter had attended the hotel's grand opening, along with a crowd of Washington VIPs, to "admire and enjoy the beautiful interior, the delightful music, and the delectable luncheon." The reporter concluded that "While the Continental will not be as large as some of the new hotels [planned for Union Station Plaza], it will be one of the prettiest and coziest."

|

| The Hotel Continental (foreground) and the Capitol Park Hotel, circa 1915 (Source: Library of Congress). |

Another hotel was already in the works when the Continental opened. The

Capitol Park, a similarly-sized hotel was completed in 1914, just three years after the Continental, on the northwest corner of North Capitol and E Streets NW. More would follow, including the

Grace Dodge Hotel for Women, located around the corner from the Continental on E Street; the

Commodore (now the

Phoenix Park) opened in 1927 at the southwest corner of North Capitol and F; the

Hotel Pennsylvania adjoining the Commodore at 20 F St NW, opened in 1926; the

Bellevue Hotel for women (now the

Hotel George) opened in 1929 on E Street across from the Dodge Hotel; and the

Stratford Hotel, next to the Bellevue at 25 E St NW, completed in 1930.

|

| This 1935 postcard, like much of the Continental's advertising, emphasized how close the hotel was to the Capitol (author's collection). |

|

| The hotel re-imagined for the Art Deco 1930s (author's collection). |

Several extensions to the "cozy" Hotel Continental were soon added, turning it into a sprawling complex. In 1916, a two-story addition provided room for a large ballroom to accommodate luncheons, dinners, and other gatherings of civic groups. In 1924, a 100-room addition was completed at the rear the main building, bringing the total number of guest suites to 250. Another large conference hall was added in the 1950s.

|

| 1930s sales brochure--click to enlarge (author' collection). |

A broad assortment of civic and religious groups held meetings at the centrally located hotel, including the Church of Two Worlds, formed by the National Spiritualist Association, which held its opening service at the Hotel Continental's ballroom in 1936. The church, which maintains that it is possible to communicate with the sprits of the dead, continued to hold services and lectures at the Continental into the 1940s. (Since 1960 it has been located in a 1906 Methodist church building in Georgetown). In 1933, 13-year-old astrologist Jack Barry captivated a crowd of 200 in the Continental's ballroom with his lecture on how all of history had been foretold in the Bible. Other groups convening at the Continental in the 1920s, 30s and 40s included a mass meeting of railway postal clerks in 1922, the formation of the Washington chapter of the National American Society, devoted to "Americanization," in 1923; annual bird shows in the 1930s of the National Capital Canary Club; the 1937 annual meeting of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty; and several meetings in the 1940s of the Curley Club, a Catholic charitable group named in honor of Archbishop Michael J. Curley.

|

| The hotel as it appeared in the early 1960s (author's collection). |

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Continental's fortunes began to decline. Many downtown hotels lost business as travelers became leery of unsafe downtown areas, which had been hollowed out by white flight to the suburbs. Further, the rise of air travel meant that Union Station's pre-eminence as the travel portal of Washington would prove to be astonishingly short-lived. As lucrative business travelers opted to stay in modern hotels further uptown, the neighborhood around Union Station was relegated to tourists arriving mostly by automobile. In 1970, the Continental's parent company opened a new Capitol Hill Quality Motel on New Jersey Avenue (now the

Yotel Washington DC) directly behind the venerable Continental. The boxy new structure was the largest motel in the city at the time.

|

| A 1960s postcard that once again emphasized the hotel's proximity to the Capitol (author's collection). |

In 1971 local investors purchased the Continental, perceiving it only as something out-of-date and unprofitable. The elegant Beaux-Arts architecture, which could have been a draw for hotel guests many decades into the future, was lost on the new owners. They soon decided to tear the beautiful building down. If it had only been able to hang on another 10 or 15 years, it would have benefited from the city's 1979 historic preservation law and doubtless would have been restored to become a flourishing grande dame on Capitol Hill. An auction was held in February 1972 (run by the same firm that had

sold off all the furnishings of the Willard Hotel in 1969). "More than 1,000 bargain hunters, antique collectors and scavengers took advantage of an unusual sale and mauled the now dead Hotel Continental, at 420 North Capitol St," the

Washington Post reported. Even several of the 20-foot marble pillars in the hotel lobby were sold (for $5,000 apiece). Soon after the building was gone.

In its place, the Hall of States, a boxy u-shaped office building designed by architect Vlastimil Koubek, took its place at 444 North Capitol Street NW in 1976. Several other neighborhood hotels, including the Capitol Park and the Grace Dodge are gone as well, although others, such as the Hotel George and the Phoenix Park, still stand. Union Station, revived as a cultural destination in the 1980s, awaits further expansion as a new wave of railroad travelers is anticipated.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included Cleland C. McDevitt, The Book of Washington (1930), John Clagett Proctor, ed., Washington Past and Present (1930); and numerous newspaper articles.

I agree that it is a tragedy that the Hotel Continental was torn down with the Quality Inn built in its place. My Uncle and cousins are to blame, as they controlled the corporation that owned the hotel. Sadly, my father had no say as he supported historic preservation. Such are family disputes.

ReplyDeleteI'd love to hear the whole story on this! If you're interested in maybe being interviewed about the Continental, contact me at streetsofwashington@gmail.com. Thanks

Delete