Pianos and the Golden Age of DC Music Stores

The sale of pianos is now a distinctly niche enterprise, but it used to form a major part of the retail industry in downtown Washington. First appearing on Pennsylvania Avenue, piano stores migrated with other retail businesses to the F Street area in the 1890s, eventually forming their own music district centered on G Street between 12th and 13th Streets. This is their story.

|

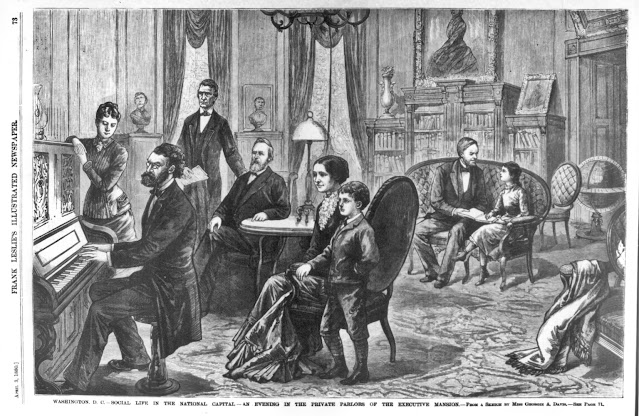

| German-born Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz plays the piano for President Rutherford B. Hayes and family. (Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, April 3, 1880, via Library of Congress). |

All of that changed in the 19th century as the piano became a universal emblem of middle class values and prosperity. Most importantly, the family piano served as a courting ground for young women (who generally abandoned it once they were married). It was a substantial investment for most households but not a prohibitive one as household incomes began to increase. American industrialists improved the durability and quality of pianos with the introduction of cast iron frames, turning out tens of thousands of pianos every year. By 1900, a million pianos were in American homes. What as once a symbol of the elite had become a ubiquitous household appliance.

Many white Americans had their first taste of African American culture through piano music. Scott Joplin and other Black artists brought ragtime, a new kind of piano music, to the American public. While the majority of piano households were white, well-to-do African American homes had them too. As a boy, Washington's Duke Ellington famously dreaded the piano lessons his parents insisted he take, tiring of having to practice every day. It paid off.

And for those without the Duke's talents, there was an easy way to avoid learning how to play: install a piano in your home that played music on its own. The "pianola," as the player piano was often called, grew increasingly ubiquitous after American engineer Edwin Scott Votey patented an instrument under that name in 1897. Until phonograph records became widely available in the 1910s, many music lovers brought home music rolls from local stores to play on their home pianolas.

Metzerott, Droop, and the Pennsylvania Avenue pioneers

In the 1830s and 1840s, several bookstores on Pennsylvania Avenue began offering sheet music and musical instruments, including pianos. By the early 1850s, the first two stores devoted exclusively to music appeared on the avenue: the Hilbus & Hitz Music Depot at 11th Street and the Richard I. Davis Music Store between 9th and 10th Streets.

.png) |

| Advertisement for W.G. Metzerott from the December 12, 1856 edition of The Evening Star. |

Many 19th century piano dealers were German Americans, products of Germany's extensive musical conservatory system and its celebrated instrument manufacturing companies. William G. Metzerott (1831-1884) was one. Metzerott learned the piano making trade in Hildburghausen, his hometown, and came to the U.S. at age 18. He first settled in New York City, where he worked alongside the Steinway brothers in the piano firm of Bacon & Raven. In 1856, Metzerott moved to Washington to take over George Hilbus' store on Pennsylvania Avenue at 11th Street NW. Metzerott eventually opened a large recital hall on the second floor over his store. Metzerott Hall became an important venue for concerts, lectures, and other social events in the decades after the Civil War.

|

| 1896 letterhead from the Metzerott Music Company, depicting its later locations (author's collection). |

During the war, Metzerott took in a future partner, Edward F. Droop (1837-1908), whose name would become one of the best known in the Washington music business. Born in Osnabrück, Germany, Droop arrived in America in 1857, first working as a tobacconist in Baltimore. Moving to Washington to stay with an uncle, he started working for Metzerott. He lived nearby on 10th Street, just a few doors down from Ford's Theatre, and was on the scene of the Lincoln assassination shortly after it transpired, keeping for the rest of his life a small cluster of flowers and swatch of red wallpaper from the President's box. A large and gregarious man sporting mutton chops that would put Chester A. Arthur to shame, Droop was also a committed bodybuilder ever ready to boast of his personal feats of physical strength.

.jpg) |

| Edward F. Droop (Source: The Washington Journal, November 13, 1897 via Library of Congress). |

By 1867, Droop became a partner in Metzerott's business, working side by side with him for the next 18 years. That year he married Sophia Schmidt of Trenton, New Jersey, a talented young singer who had been contemplating a career as a concert vocalist before marrying Droop. Sophia, known as Sophie, was the younger sister of Rosa Cluss, the wife of celebrated architect Adolf Cluss. Within the tight-knit local German community, it was the Clusses who introduced Droop to Sophie. In addition to bearing two sons with Edward, Sophie charmed Washingtonians as an amateur choral singer. Tragically, in 1874 she died from tuberculosis at just 29 years old. The Washington Saengerbund performed at her funeral at Oak Hill Cemetery, with hundreds in attendance.

|

| The Droop store on Pennsylvania Avenue, circa 1887. (Source: Library of Congress) |

After Metzerott died in 1884, Droop inherited the music store, fending off a legal challenge from Metzerott's widow. Henrietta Metzerott and her sons subsequently opened a separate Metzerott's store on F Street, while Droop continued at the Pennsylvania Avenue address under his own name. Droop's Music House became one of the best known DC stores and a major dealer in Steinways and other pianos. "Every American Citizen should have a piano in his home," declared a 1907 Droop's advertisement. "Years ago, this was a luxury; now it is almost a necessity." At the time of Droop's death in 1908, his store was said to be the oldest continually operating commercial store on the avenue. His sons Edward H.—an accomplished musician—and Carl continued the business for many more years, at least into the 1940s, eventually adding a second store at 13th and G Streets NW.

|

| Washington's piano merchants faced stiff competition from out-of-towners like New York-based Freeborn G. Smith, who sold Bradbury pianos at 1103 Pennsylvania Avenue (author's collection). |

De Moll and Juelg: The Rise of G Street

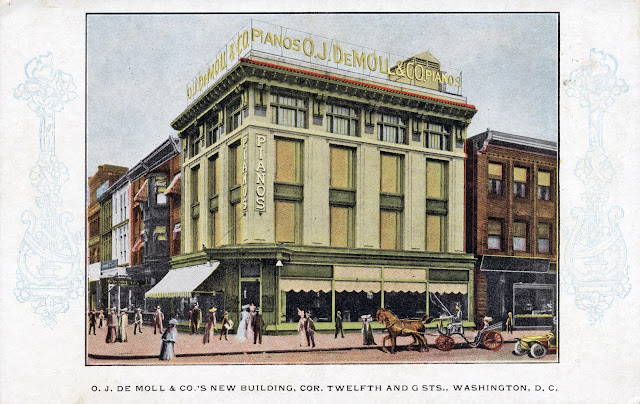

In the early 1900s, music stores had begun to clusters in the blocks around F, G, 12th, and 13th Streets NW, largely abandoning Pennsylvania Avenue. Among the dealers to set up shop here was Otto J. De Moll (1878-1942), a DC native who got an early start in the music business. In 1902, at age 24, he took over Henry White's music store at 1231 G Street NW, just as piano sales were reaching their peak years across the nation. A 1904 advertisement in The Washington Post, called De Moll "one of the youngest, yet oldest in point of experience, in the business." Four years later, De Moll needed more room and commissioned a new, four-story building on the southwest corner of 12th and G Streets to house his growing store.

|

| In 1909, Otto J. De Moll's piano store moved into this new building, designed by B. Stanley Simmons, on the southwest corner of 12th and G Streets NW. (Author's collection). |

Designed by B. Stanley Simmons, one of Washington's best architects, the new building provided space on the first floor for baby grands and art-case (highly decorated) pianos as well as mahogany-paneled offices for transacting business. The second and third floors housed player pianos and square pianos, while the top floor was for music rolls. Customers could try out the rolls on player pianos in a soundproof room. The repair department was also on the fourth floor. All floors were serviced by a "modern combination electric passenger and freight elevator." The company prospered at this location, remaining in business until the 1950s.

|

| Etching of the Juelg Piano Company store at 13th and G Streets NW, from a business card (author's collection). |

At the other end of the same block, another piano entrepreneur soon set up shop. Born in Peoria, Illinois, Harry H. Juelg (1875-1953) was a salesman who tried his hand at a variety of products. In 1900, he co-owned a bicycle shop in Peoria, but within a few years he moved to Washington, where he jumped into the red-hot player piano business, selling new and used pianos at 1206 G St NW, across the street from De Moll's. His firm grew to some 50 employees, prompting the construction of a new, four-story store on the northeast corner of 13th and G Streets NW, in 1912. In addition to player pianos, Juelg sold sheet music and piano rolls from this store, claiming it was the largest piano roll exchange in the south. But the Juelg Company was destined to be short-lived. Juelg sold the store in 1915 and moved to Baltimore, where he became a manager in the Maryland Piano Company and later an automobile salesman.

Jordan and Kitt

Jordan would come to Washington to visit his sister, and he began investing in real estate here in the 1910s. In 1912, he was the owner of the new building being constructed for the Juelg Piano Company. He took the next step in 1915, jumping into the piano business by buying out the Juelg company as well as another nearby piano store run by George Kennedy. By 1917 Jordan had consolidated the two in the former Juelg building under the new name of the Arthur Jordan Piano Company.

|

| Crowds form outside the Homer L. Kitt store in this undated photo from the 1930s (author's collection). |

Jordan called on an old friend, Homer L. Kitt (1880-1944), who was running a music store in Chicago, to come to Washington and take over management of the Jordan store. Born in Huntington, Indiana, Kitt began his career in a piano factory there. He seems to have been an excellent manager, the Arthur Jordan Piano Company prospering under his watch. In 1922, the company purchased another G Street rival, the DC branch of Knabe Warerooms, Inc., located at 1330 G Street NW. Knabe was a venerable piano manufacturer with roots going back to 1835, when German immigrant William Knabe founded the company in Baltimore.

Kitt personally took over operations of the former Knabe store, rechristening it the Homer L. Kitt Company. Though the Jordan and Kitt stores were both owned by Jordan, they appeared to be rivals, selling different brands of pianos and undoubtedly gaining more business overall than if the two stores had been merged. Their separate sales forces were said to be fierce rivals of each other. The Kitt store, originally sporting an elaborate Spanish Revival facade, was seriously damaged in a fire in September 1938 that was determined to be arson. After the store was rebuilt, it featured a stylish Art Deco look.

|

| Postcard showing the rebuilt Kitt's Music Store (author's collection). |

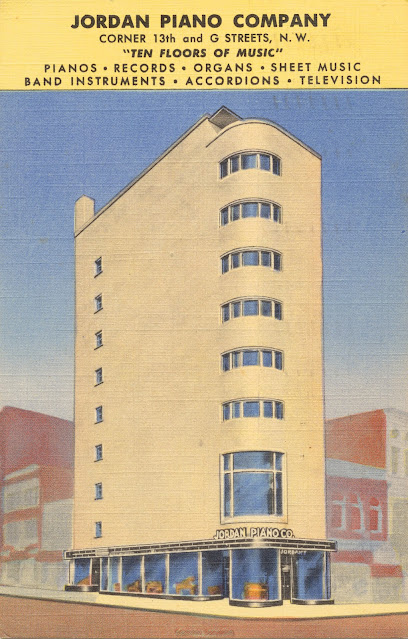

In 1949, the Jordan Company took a much more dramatic step, replacing its store with a slender, nine-story “skyscraper,” designed by the firm of Donald S. Johnson and Harold L. Boutin. The streamlined, International-style structure wrapped around the corner in a smooth curve, its limestone façade looking distinctly out of place as it shot up from the surrounding motley assortment of older commercial structures. Five of the ten floors contained pianos, but at this point Jordan also devoted considerable space to radios, phonographs, and televisions. Kitt's did the same.

|

| Postcard of the new Jordan Piano Company building, which replaced the former Juelg building at 13th and G Streets NW in 1949 (author's collection). |

Piano sales had begun to plummet in the 1920s. More than half of all piano sales in 1910 had been player pianos, but those sales evaporated after the advent of radio and the proliferation of phonographs. The last American player piano was manufactured in 1932. Although the golden age of pianos had ended, Jordan's and Kitt's continued in business. The Arthur Jordan Foundation, which owned both, finally merged them into Jordan-Kitt's in 1968. The store at 1330 G Street was the last music store operating in downtown Washington when it closed in 1986. It was not the end of the Jordan-Kitt's Music Company, however. The firm continues to do business to this day with four locations in Maryland and Virginia.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included: Gerald Carson, “The Piano in the Parlor,” American Heritage (Dec 1965); Rachael Christian, "William Metzerott and the D.C. Music Trade," Washington History (Fall 2016); James Parakilas et al., Piano Roles: Three Hundred Years of Life with the Piano (1999); Frank H. Pierce III, The Washington Saengerbund: A History of German Song and German Culture in the Nation's Capital (1981); Adolf Cluss: From Germany to America - Edward F. Droop House; and numerous newspaper articles.

Comments

Post a Comment