The city's historic structures were built from materials as unique to their age and as varied as the architectural styles used to mold them into buildings. Those materials often have their own rich stories to tell, as Garrett Peck ably demonstrates in his lively new book,

The Smithsonian Castle and the Seneca Quarry. Seneca sandstone has a lot going for it. In addition to its rich, dignified color, it also has the unique property that it is relatively soft and easy to cut when it is taken out of the ground but hardens after the cut stone is set in place, making for an excellent building material. It's a wonder that more D.C. buildings are not made from it.

The first quarry to be used heavily in constructing early Washington was the Aquia Creek quarry near Stafford, Virginia. Peter L'Enfant purchased that quarry on behalf of the government to supply stone for the Capitol and White House, but the pale Aquia Creek sandstone discolored easily (one reason why the White House was painted white in 1798), and better sources of stone were sought out. The cliffs along the Maryland side of the Potomac at what is now the small village of Seneca offered superior stone.

Robert Peter (1726-1806), a Scottish immigrant who became a prosperous Georgetown tobacco merchant, purchased a large tract of land in Maryland, including the sandstone cliffs, in 1781. The first small amounts of stone were quarried there some time in the late 18th century. Peter's son Thomas built the regal

Tudor Place mansion that still stands today in Georgetown as one of the city's best house museums. Thomas also built a distinguished country house on the land at Seneca, but it was not until Thomas's son, John Parke Custis Peter (1799-1848), inherited the property that the Seneca Quarry started to figure prominently in D.C. construction.

|

| South side of the Castle (photo by the author). |

John P.C. Peter made a daring lowball bid in 1846 to supply the stone for the new Smithsonian Building to be constructed on the Mall. The iconic structure could have been made of pale Aquia Creek sandstone, white New York marble, or gray granite, but at a below-market 25 cents per square foot, Peter's Seneca red sandstone got the nod from the building committee. The eccentric Romanesque Revival building, designed by James Renwick, set the stage for the Victorian era of red Washington architecture. While many red Victorian buildings would be made primarily of brick, Seneca sandstone was prominent as well, often used in water tables because it was considered waterproof.

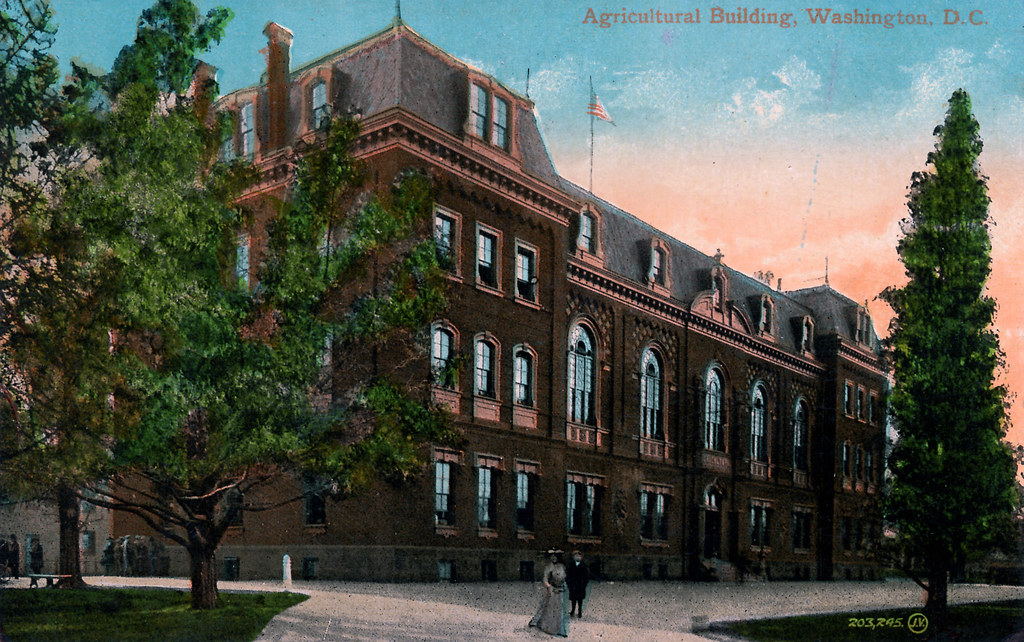

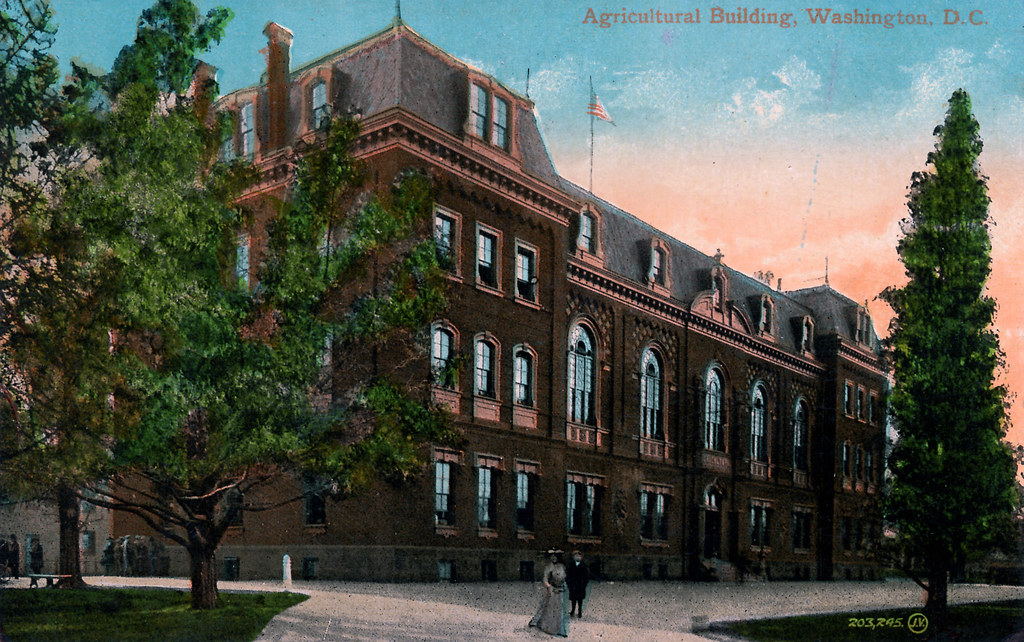

|

| The water table and belt courses on the old Agriculture Building are of Seneca sandstone (author's collection). |

Renwick used the stone as trim for the original Corcoran Gallery of Art building (now the Smithsonian's

Renwick Gallery) as well as the chapel at

Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown. Just to the west of the Castle, the original Agriculture Department building, designed by Adolf Cluss and completed in 1868, had a Seneca sandstone water table and belt courses. Other Seneca buildings past and present, as cataloged by Peck, include a number of C&O Canal locks and houses, the McClellan Gate at Arlington National Cemetery, the

Luther Place Memorial Church facing Thomas Circle, and many private houses. Although he hasn't found evidence to confirm it, Peck tells me he suspects the trim and belt courses on the striking National Security & Trust building at 15th Street and New York Avenue NW may be Seneca sandstone as well.

+detail.jpg) |

| It's possible that the trim on this building is Seneca sandstone (photo by the author). |

But Peck's book goes beyond the buildings to delve into the fascinating stories of the people behind the stones. John P.C. Peter died unexpectedly in 1848 after scratching his thumb on a rusty nail and contracting tetanus, but the quarry continued to prosper without him. It was the site of a skirmish during the Civil War and a scandal afterward, when it fell into the hands of robber barons during the corrupt years of the Grant administration. Peck fills in all the details of these episodes and paints a vivid picture of quarry life, including the role of African-Americans who did much of the stone-cutting.

|

| Ruins of the stonecutting mill (photo by the author). |

The quarry shut down around 1901, having exhausted the best of the redstone that was readily available. By that time Washingtonians had decided the city's old red architecture was bad-bad-bad and should be replaced by the imperial white marble and limestone piles envisioned by the McMillan Commission. The forgotten quarry site gradually fell into ruins. Today it lies in densely overgrown parkland just east of the C&O Canal at Seneca. In winter months, when the undergrowth is dormant, Peck leads tours of the site. Though the quarry and its various related structures stand on parkland, none are marked with interpretive signs, and there is no marked trail through the site, so Peck's extensive knowledge of the old quarry is essential. The ghostly ruins of the old stonecutting mill, with initials carved in the sandstone by workers of yore, are particularly poignant.

|

| Quarry master's Seneca sandstone house (photo by the author). |

It would be a great addition to the cultural resources of the Washington area if the Seneca Quarry site could be turned into an historical park, as Peck envisions. He closes his book with an engaging discussion of the individuals who have saved parts of old Seneca, like the Kiplingers, who own Thomas Peter's country mansion

Montevideo, and the Albiols, who have restored the old quarry master's house. Peck argues for a modest investment to clear the brush from the stonecutting mill site and other key spots, lay out a marked trail through the park, and install a few key interpretive signs. It would make for a unique memorial to a distinctive aspect of 19th-century culture. With publication of

The Smithsonian Castle and the Seneca Quarry and fresh interest in the site, perhaps the

Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission might take action.

+detail.jpg)

You mention that Peck offers tours during the winter months - where might one find information on those?

ReplyDelete-

Thanks for sharing this information and providing the links to other buildings that have been built with the red Seneca stone.

-

A park would be perfect for that area!

For news about tours, I recommend checking out the Facebook page for the book at http://www.facebook.com/CastleandtheQuarry

DeleteUnfortunately, there won't be many more tours this season before spring growth makes them impossible.

Thanks John .. I'll head over that way .. if not this year .. for certain .. next! The book looks interesting .. will look to read it after your book ...

DeleteHi John-

ReplyDeleteLoved your post about the Northumberland--am pals with Patrick Sheary as well as some former residents. It really is a wonderful old building and a time capsule of sorts.

Also saw this post and wanted to mention my growing up in upstate NY--the real upstate on the St. Lawrence River in Ogdensburg not the Scarsdale "upstate" of Hil and Bill--with the equally reknowned Potsdam Sandstone. When I first came to DC in the late 1970s and noticed the old-fashioned sandstone buildings here and there, it was like being back home.

http://www.potsdampublicmuseum.org/

These days, I rarely get up north but it looks like there is some good cultural tourism going on around the old sandstone industry.

Regards,

Elizabeth Elliott

Foggy Bottom

Wonderful entry about a wonderful story. Planning to obtain Peck's book!

ReplyDeleteThanks for this column!

Odds are that this " Peck tells me he suspects the trim and belt courses on the striking National Security & Trust building at 15th Street and New York Avenue NW may be Seneca sandstone as well." is not true, but the trim is most likely Potsdam Sandstone, which was used for many buildings in the New York Metropolitan area. Jane LaLone, native of Potsdam, NY.

ReplyDelete