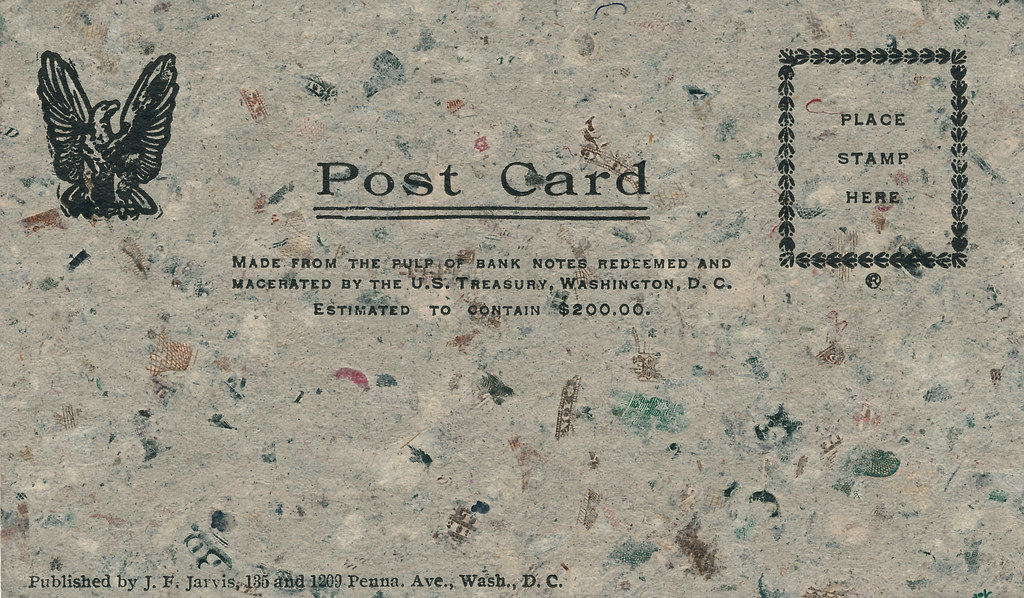

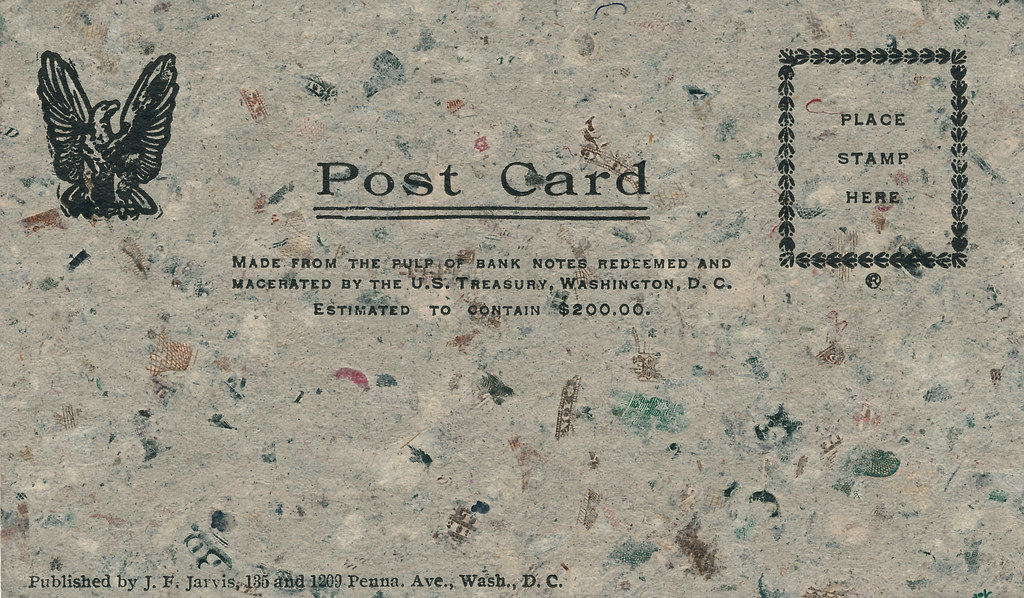

What to do with worn-out paper currency? Macerate it! Today's picture is of a classic tourist souvenir from the early years of the 20th century—a postcard made from macerated currency.

|

| (Author's collection) |

Aside from the notorious "Continentals" issued to help finance the American Revolution, paper currency did not come into general use until the Civil War. An act of Congress in 1862 authorized the Treasury Department to come up with a method for destroying old paper notes that were no longer fit for circulation. At first they were burned in a special furnace located on the "White Lot" behind the White House, but this method proved to be problematic. It was hard to thoroughly incinerate bundles of notes, and undestroyed fragments could escape through the chimney. Enterprising individuals would scour the White Lot for fragments of bills that they then submitted to the Treasury Department for replacement, claiming the notes had been accidentally burned. Treasury officials soon caught on to the scam, however, and looked for a better way to destroy old bills.

|

| Burning old money in the White Lot furnace (source: Mary Clemmer, Ten Years in Washington or Inside Life and Scenes in Our National Capital as a Woman Sees Them, published in 1882). |

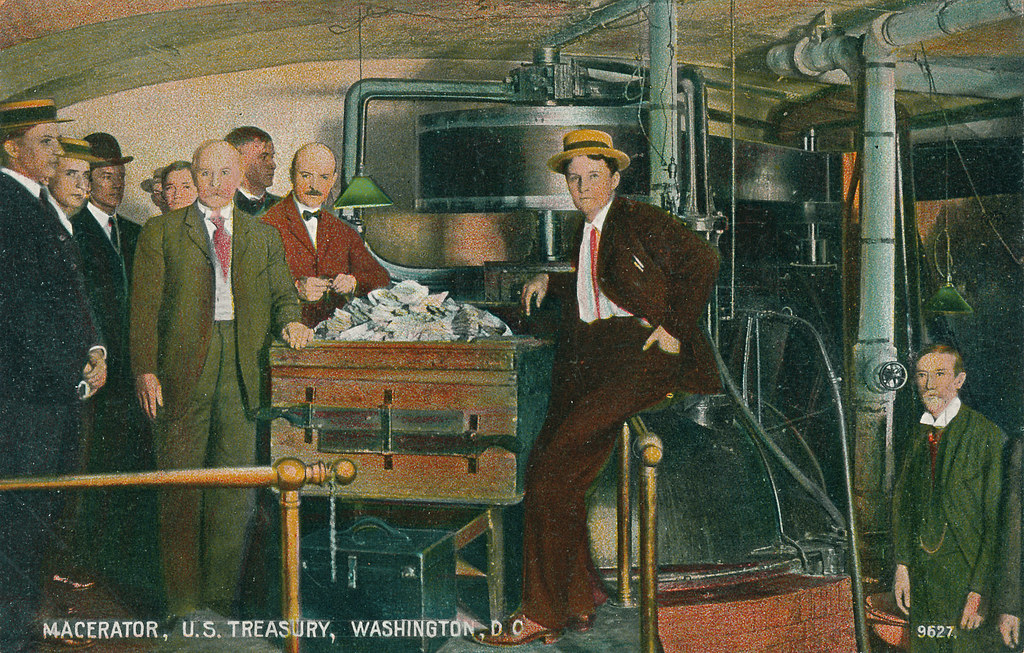

In 1874 a new method of destruction was approved: maceration, the shredding of the bills into millions of tiny worthless bits of paper. The curious thing is that this tedious procedure, borne of practical necessity, blossomed into one of Washington's biggest tourist attractions in the late 19th century. Charles M. Pepper, writing in

Every-Day Life in Washington in 1900, found the maceration process "one of the most entertaining features of the Treasury Department." Tourists, after seeing how new money is made at the

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, could visit the Treasury and be taken down to a "sub-cellar room hid away from the face of the earth." There they would witness Treasury employees dumping millions of dollars worth of worn currency into the macerating machine, which dutifully chewed it all into confetti. It was great fun.

And of course, as always, the best part of being a tourist is purchasing souvenirs, and macerated currency made for some unique items. In addition to postcards, souvenir shops on Pennsylvania Avenue offered a variety of medallions and other trinkets, including little Washington Monuments and busts of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln that were advertised to be made from $20,000 worth of currency.

The

Washington Post reported in 1903 that over 30 "remembrance shops," "souvenir stores," and "memento stands" graced the Avenue selling all sorts of baubles like these. The advent of such tourist traps was seen as a welcome relief for Washington's famous public buildings and monuments. In earlier days, before the business got started, visitors would regularly resort to vandalism to create their own D.C. souvenirs, chipping off bits of the Washington Monument, breaking off a fragment of the White House wall, or even whittling a shaving off the leg of a chair in the Capitol. The incidence of such souvenir-driven vandalism reportedly declined significantly after ready-made souvenirs came on the market.

Apparently there is some unwritten law that requires all cheap souvenirs to be made in a single foreign country. Lately it has been China, before that Taiwan, and several decades ago Japan. In 1903 it was Germany, credited by the

Post with inventing the cheap souvenir industry. After flooding European cities with their wares, the Germans "then invaded the American market, and to-day every place of interest, from the Capital to Pike's Peak, and from Niagara Falls to St. Augustine, Fla., is supplied with trinkets made in Germany." And why couldn't American manufacturers compete with the Germans? The usual reason: the cost of labor. "Here is a cup and saucer of excellent china, with a picture of

Cabin John Bridge on one side and Arlington on the other. It sells for 75 cents. If made in this country, $2.25 is the lowest price at which it could be sold."

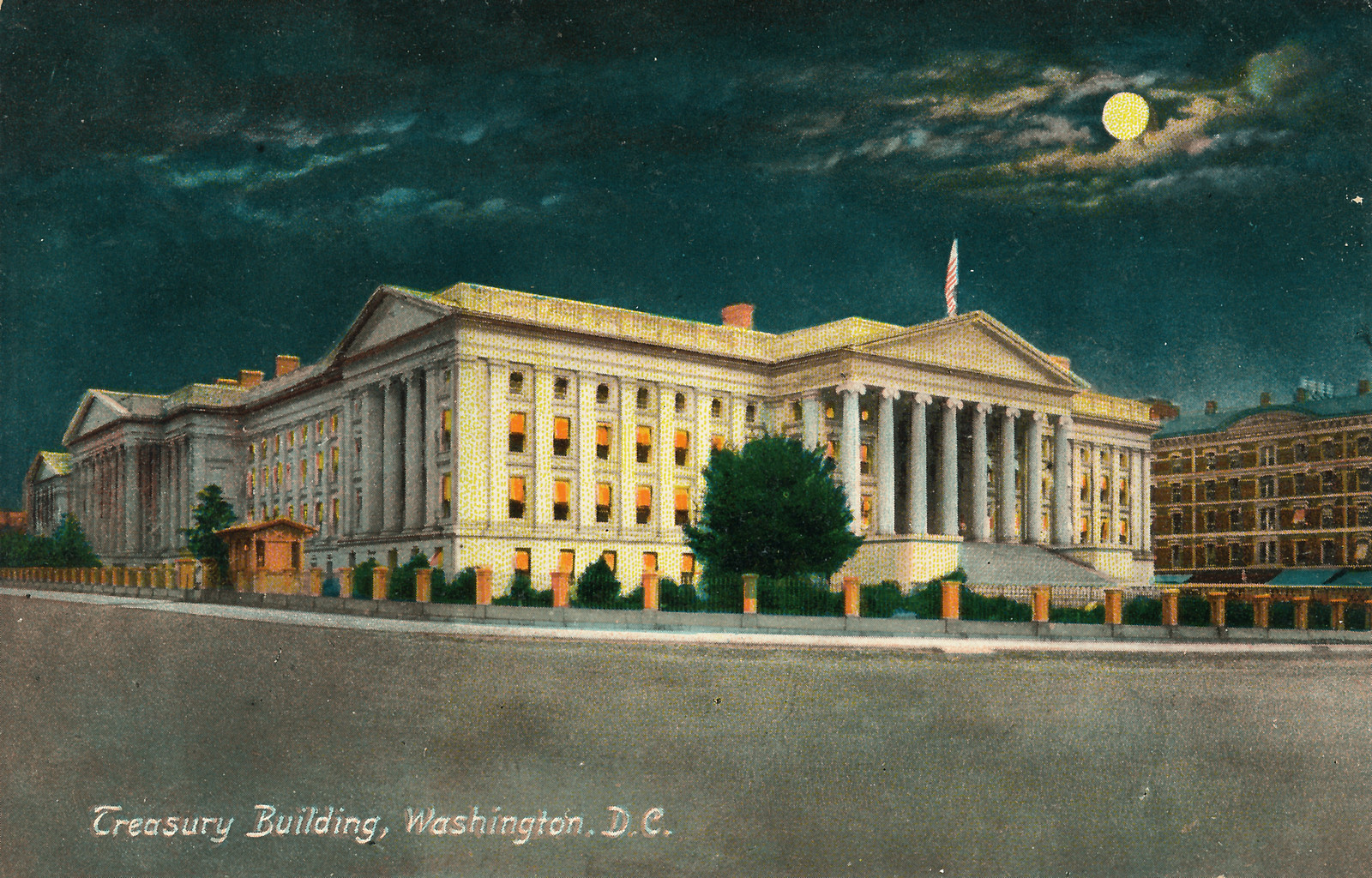

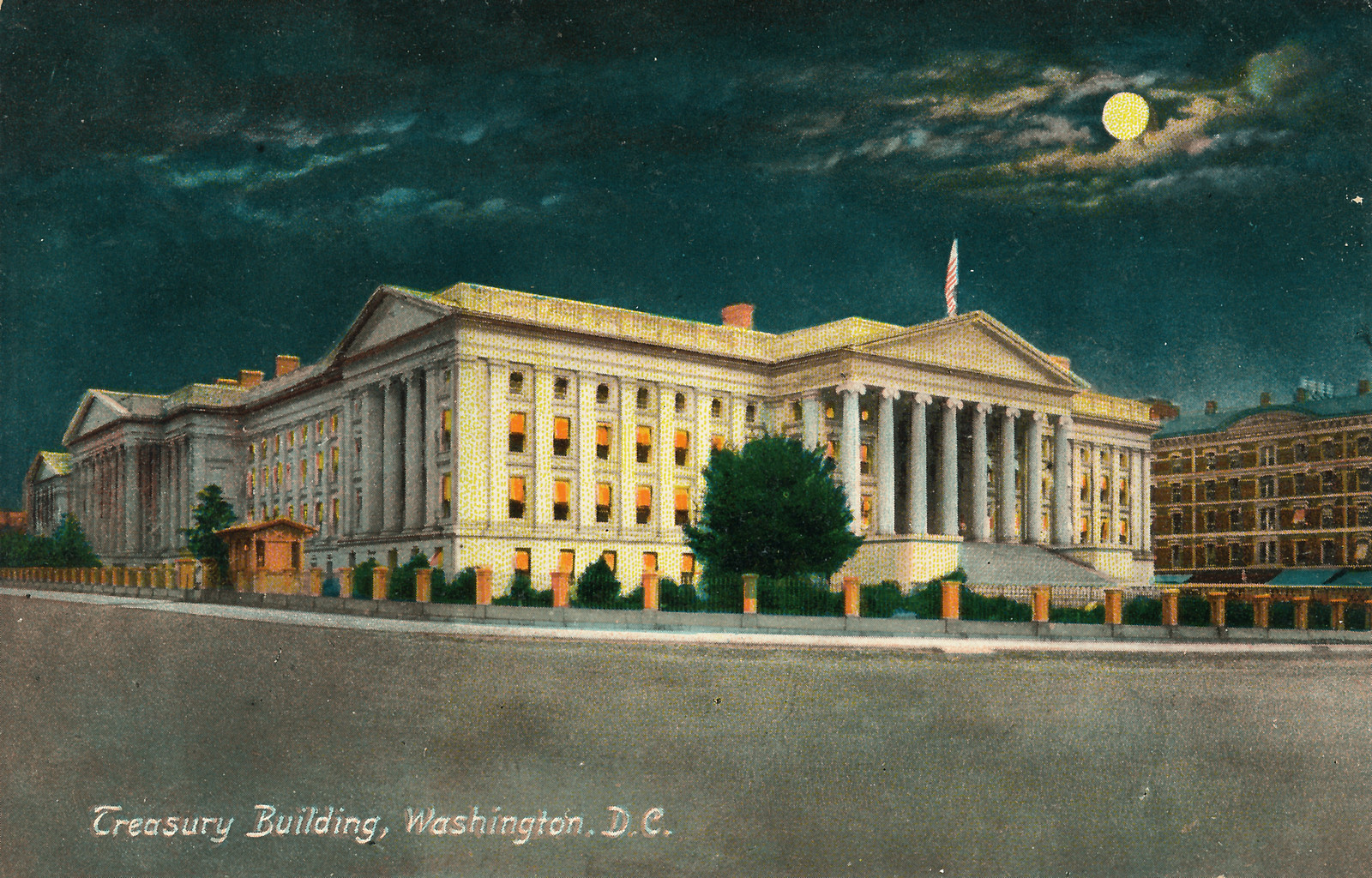

|

| Dramatic nighttime views of major buildings and monuments were popular in the early 1900s. This hand-colored postcard was printed, naturally, in Germany (author's collection). |

Even postcards, still mostly printed in the U.S. in 1903, were under pressure from the Germans, who would soon dominate that part of the market as well, producing a multitude of exquisitely colored cards until World War I cut off trade. The only small niche in the market not dominated by Germany was that of the macerated money souvenirs and postcards, proudly made in Washington by James F. Jarvis, among others.

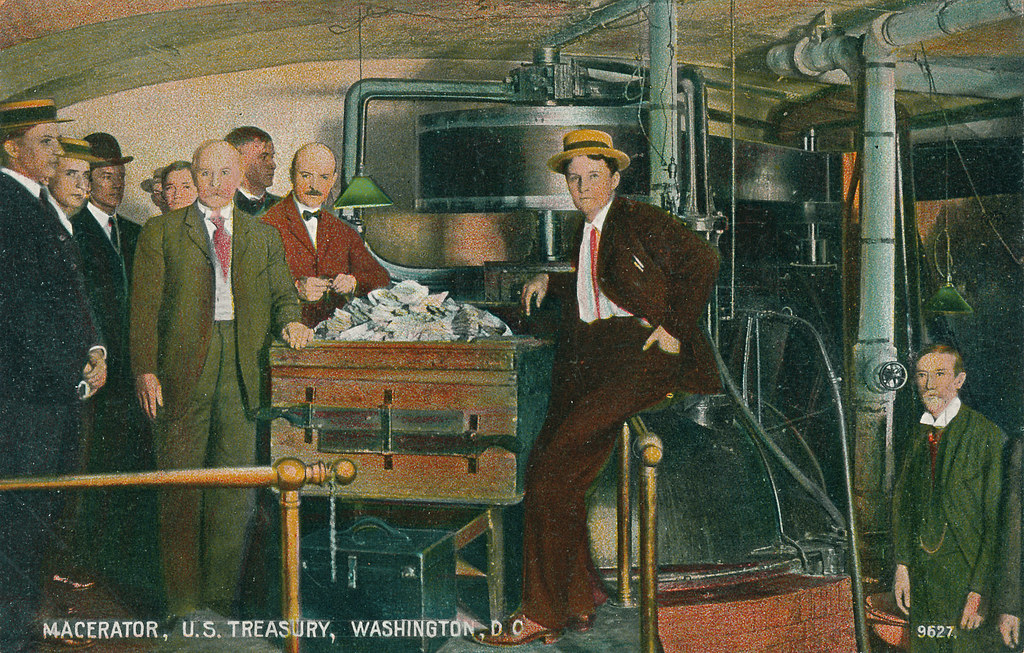

|

| Postcard view of the new Treasury macerator, circa 1915 (author's collection). Visit Shorpy for another view of a macerating committee. |

But even that booming business was not destined to last long. Just five years later, in 1908, the

Post wrote again about the maceration process. An unfortunate change was at hand: "No longer will remote likenesses of George Washington, or the shaft of masonry that bears his name, representing vast sums of money, be manufactured by clever artificers from the papier mâché of the bureau of engraving and printing and the Treasury Department. A new macerating machine, involving a chemical process, does not permit even that ghostly green tint that formerly enveloped these relics with some of the glamour that attaches to the magic cash which they represented." The new machine dissolved the old notes into a homogenous gluey pulp, and to make matters worse, "vistors are not admitted into the macerating room." Just like tours of the FBI building, a popular attraction suddenly vanished, and along with it a very distinctive genre of souvenirs.

|

| Manufacturing uniform slabs of pulp from macerated currency at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1914. The pulp was sold to make cardboard and other low-grade paper products (Source: Library of Congress). |

Today turn-of-the-century macerated souvenirs are rare and highly sought after by collectors. But the freshly macerated shreds of worn-out currency can still be obtained, if you know where to look. Visitors who tour the Treasury Department building receive little packets of macerated currency as souvenirs. It's well worth getting up early on a Saturday morning to see the inside of one of Washington's handsomest public buildings and to get your own macerated memento—for free.

I'd like to go back to that era when people would buy goods using bullion coins and how it's carefully hidden in a pouch made of flour bags.

ReplyDeleteI have a macerated capital plaque that I cannot find a photo of , it is of the capital and also has an American flag just above and what looks like drapes hanging . I believe it to be a very early piece possibly 1930:s because grandma owned it and it would have been hers maybe around that time ,any info would be appreciated . anyone with info may contact me at Sammy.Casarez@yahoo.com . thanks so much

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete