The Aqueduct Bridge, Gateway to Georgetown

Before the magnificent Francis Scott Key Bridge was completed in 1923, a far homelier structure linked Georgetown to Rosslyn. Known as the Potomac Aqueduct or Aqueduct Bridge, it was born of Alexandria's aspirations to rival Georgetown as a commercial hub. A remarkable engineering achievement, the bridge served as a vital Potomac crossing for 80 years.

|

| The Potomac Aqueduct, c. 1865. Source: Library of Congress |

It all began with construction of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal in the 1820s. The canal project was a long, complex, and expensive effort originally intended to spur commercial trade with Georgetown (and Washington) by establishing an economical transportation link to the vast and fertile Ohio Valley. It turned out to be too expensive to build it all the way across the mountains to the Midwest, and it never lived up to its investors' early hopes, but in the 1820s it seemed like the next big thing for the city. Alexandria merchants sorely wanted to get in on this expected action. It would have been too expensive to unload canal boats arriving in Georgetown and reload them on river boats to take them down to Alexandria, so a non-stop method was needed to get the canal boats to Alexandria.

The solution was to build an aqueduct bridge over the Potomac and connect it to a canal on the Virginia side to carry boat traffic down to Alexandria. Congress granted a charter to the Alexandria Canal Company in 1830 and pitched in $100,000 to support the project, which was to be privately owned. Work began in 1833 on both the bridge and the Alexandria canal and lasted a full decade. (All that's left of the canal is a recreated lock at the privately-owned Tidal Lock Park on the Alexandria Waterfront.)

When Congress stepped in, it put the U.S. Topographical Engineers, predecessors of the Army Crops of Engineers, in charge of the bridge work. Captain William Turnbull (1800-1857) headed this daunting task. Building the bridge's piers was the biggest challenge. The plan was to construct cofferdams at appropriate spots in the river, pump the water out and then build the piers inside them. However, they had to be built at an incredible depth—through 18 feet of water and 17 feet of silt—to reach a solid bedrock foundation. River cofferdams had never been built so deep before. The first ones erected leaked mercilessly and had to be completely replaced. The second set were little better, filling with water after an hour or so and with mud oozing in from below.

As recounted by Pamela Scott, Turnbull was clearly concerned that the deep and unproven cofferdams—even when finally watertight—might not hold up while the bridge piers were being constructed inside them. In his journal, he observed that the spectacle of "men busily at work so far below the surface of the river, seemed to interest the public exceedingly; but to the engineer, whatever might be his confidence in the ability of the dam to resist the immense weight which he knew to be constantly pressing upon it in the most insidious form, the sight was one which filled him with anxiety, and urged him to the most unceasing watchfulness."

The solution was to build an aqueduct bridge over the Potomac and connect it to a canal on the Virginia side to carry boat traffic down to Alexandria. Congress granted a charter to the Alexandria Canal Company in 1830 and pitched in $100,000 to support the project, which was to be privately owned. Work began in 1833 on both the bridge and the Alexandria canal and lasted a full decade. (All that's left of the canal is a recreated lock at the privately-owned Tidal Lock Park on the Alexandria Waterfront.)

When Congress stepped in, it put the U.S. Topographical Engineers, predecessors of the Army Crops of Engineers, in charge of the bridge work. Captain William Turnbull (1800-1857) headed this daunting task. Building the bridge's piers was the biggest challenge. The plan was to construct cofferdams at appropriate spots in the river, pump the water out and then build the piers inside them. However, they had to be built at an incredible depth—through 18 feet of water and 17 feet of silt—to reach a solid bedrock foundation. River cofferdams had never been built so deep before. The first ones erected leaked mercilessly and had to be completely replaced. The second set were little better, filling with water after an hour or so and with mud oozing in from below.

As recounted by Pamela Scott, Turnbull was clearly concerned that the deep and unproven cofferdams—even when finally watertight—might not hold up while the bridge piers were being constructed inside them. In his journal, he observed that the spectacle of "men busily at work so far below the surface of the river, seemed to interest the public exceedingly; but to the engineer, whatever might be his confidence in the ability of the dam to resist the immense weight which he knew to be constantly pressing upon it in the most insidious form, the sight was one which filled him with anxiety, and urged him to the most unceasing watchfulness."

|

| Aqueduct Bridge during the Civil War (Source: Library of Congress). |

Once the bridge was finally completed in 1843, it was a distinctly unattractive structure. There wasn't enough money for a stone aqueduct to be built on the sturdy granite piers, so a wooden one was constructed, complete with a forest of supporting timbers that made the thing look from the river like it was covered with scaffolding and still under construction. Still it was praised at the time as an engineering marvel.

|

| The bridge as seen from the Virginia side, c. 1865 (Source: Library of Congress). |

At the onset of the Civil War in 1861, the government temporarily took over the bridge, as it did with many Washington structures, and converted it for use as a road, draining the trough of the aqueduct and building a ramp down to it from Bridge Street (now M Street) in Georgetown so that it could be used as a roadway. During the war, the bridge ferried teams of supply wagons to and from Northern Virginia. It was defended by several blockhouses and earthen forts on the Virginia side that were intended to put up just enough of a fight to allow retreating Federal troops to get across the river in the event of a major defeat. The bridge remained as a wagon road until 1866, when the Army returned it to its owners, who in turn leased it to the Alexandria Railroad and Bridge Company.

The new owners saw lots of potential profit in this unique river crossing. They removed the old wooden base section of the bridge and replaced it with a new one for use once again as an aqueduct. Above that they built a sturdy wooden superstructure, supported by graceful arching trusses, to carry a new toll road across the river.

The new owners saw lots of potential profit in this unique river crossing. They removed the old wooden base section of the bridge and replaced it with a new one for use once again as an aqueduct. Above that they built a sturdy wooden superstructure, supported by graceful arching trusses, to carry a new toll road across the river.

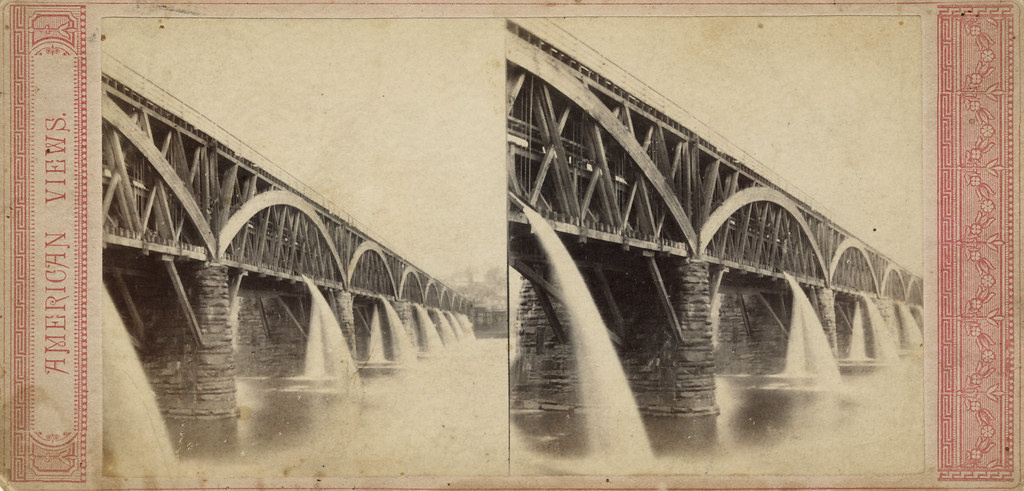

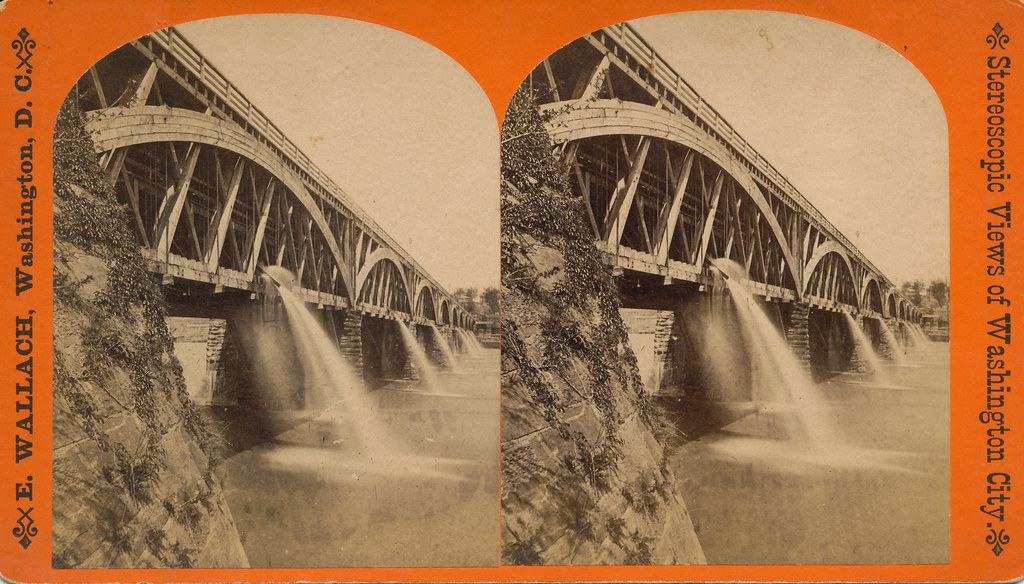

No sooner did the bridge open, however, than complaints about it began pouring in. Virginia farmers were upset about the high tolls the Bridge Company was charging. The Aqueduct Bridge was the most efficient route for many of them to take their produce to Center Market, and the high tolls cut into their income. Georgetown residents likewise felt unfairly constrained from crossing the river by the exorbitant expense. But this wasn't the only way local residents were being soaked—the lower aqueduct section of the bridge leaked profusely, creating a nuisance for river traffic. As reported in The Washington Post in 1885, the Columbia Boat Club complained that the bridge's "present condition is very obnoxious to all persons who are fond of boating, for there is not a single arch under which they can go without receiving a drenching from the continual downpouring of water from the leaks above."

|

| Stereoviews of the second Aqueduct Bridge. The slow exposure dramatizes the leaky aqueduct (Author's collection). |

As early as 1881, the government began taking action to seize control of the bridge and make it a free, public crossing. An offer was made to buy the bridge, but the owners resisted. They were finally pressured into selling in 1886. At this point, planning for he bridge's third and final incarnation began under the direction of Lt. Col. Peter Hains (1840-1921), a prominent Army engineer who would later design the Tidal Basin and for whom Hains Point is named. Under Hains' direction, the entire wooden superstructure was removed from the bridge, the aqueduct was abandoned altogether, and a new iron truss bridge was constructed on the original stone piers.

The opening of the new bridge on April 11, 1888, was cause for a massive celebration in Georgetown. Flags, streamers, and bunting of all sorts adorned Bridge Street, and more flags fluttered from the new bridge itself. According to The Washington Post, "the most extensive celebration ever held" in Georgetown "or West Washington, as it is now called" was held, complete with marching bands and long-winded speeches. Everyone was delighted to have a free bridge at last.

The opening of the new bridge on April 11, 1888, was cause for a massive celebration in Georgetown. Flags, streamers, and bunting of all sorts adorned Bridge Street, and more flags fluttered from the new bridge itself. According to The Washington Post, "the most extensive celebration ever held" in Georgetown "or West Washington, as it is now called" was held, complete with marching bands and long-winded speeches. Everyone was delighted to have a free bridge at last.

|

| Postcard view circa 1910 (Author's collection). |

Of course, any history of a bridge like this one has to include a survey of those who couldn't resist jumping off of it. The first person to jump off the new iron bridge was an unidentified "middle-aged white man" in October 1890 who, according to the Post, threw his hat on the bridge floor, climbed over the railing, and "leaped out into the air, his figure sharply outlined against the sky, and then dropped like a stone through the hundred feet of air between the bridge and the water below. When the man struck the water he cut it like a knife, falling almost perpendicularly. The water splashed up and the body disappeared." All that was left for the police to work with was the hat he had left behind.

The bridge was actually closer to 60 feet high than 100, and a number of people jumped off without suffering any harm. In June 1894, William Aldurfer, a soldier at Fort Myer, jumped into the water on a $50 bet. He swam ashore without suffering any harm. He was greeted by so much adulation from awestruck bystanders that he went right back out on the bridge and did it again, just for kicks. Later that same year, 19-year-old Flora Smith, crestfallen that her true love had found another woman, leapt from the bridge but was saved by the crew of a passing tugboat. Miss Smith was a maid in the household of Army Captain M. C. Foote, and her erstwhile lover, like Mr. Aldurfer, was a soldier at Fort Myer. Captain Foote, upon learning the reason for Flora's distress, promptly had the young soldier court-martialed.

Two years later Marcia Hopkins, a clerk in the Sixth Auditor's office of the Treasury Department, decided to end her woeful life by jumping from Aqueduct Bridge. She survived without a scratch and with a fresh attitude about life to boot. As recounted in the Post, she stated: "I must confess now that most of my trouble was fancied. I thought the devil was after me, and would only be satisfied when I was dead, but I am rid of him forever. God came to my rescue, and life is as sweet to me now as when I was a little girl, romping about without a care of any kind."

Jerry McCoy tells the story of the unfortunate DC cop, John Jacob Smith, who was assigned to the Aqueduct Bridge on the 4th of July in 1904. A group of carousing soldiers from Fort Myer (apparently an endless source of Aqueduct Bridge antics) were headed into Georgetown to celebrate that evening and stopped near the Georgetown end of the bridge, blocking others from passing. Officer Smith tried to get them to move on, but one of the soldiers, 23-year-old Samuel R. Young, took out his pistol and shot the officer several times in the abdomen. Young thought he was just being mischievous because his gun was loaded only with blanks. The blanks were nonetheless powerful enough to fatally wound Officer Smith, who died after surgery several days later. Smith was only the 7th DC police officer killed in the line of duty.

Needless to say, the bridge that was hosting all of this drama posed a number of safety issues. Since the 1890s, officials had worried that the bridge was too narrow and rickety for the traffic it carried. After the flood of 1889, some of the piers seemed to be deteriorating, and in 1903 an expensive two-year effort began to replace one of them. Other piers were repaired in subsequent years. According to the Baltimore Sun, the District's commissioners argued as early as 1902 that a more attractive stone arch bridge should be built in its place. Congress finally acted in 1916, authorizing the construction of a replacement bridge, and the Army Corps of Engineers began work on the Key Bridge in 1917.

The bridge was actually closer to 60 feet high than 100, and a number of people jumped off without suffering any harm. In June 1894, William Aldurfer, a soldier at Fort Myer, jumped into the water on a $50 bet. He swam ashore without suffering any harm. He was greeted by so much adulation from awestruck bystanders that he went right back out on the bridge and did it again, just for kicks. Later that same year, 19-year-old Flora Smith, crestfallen that her true love had found another woman, leapt from the bridge but was saved by the crew of a passing tugboat. Miss Smith was a maid in the household of Army Captain M. C. Foote, and her erstwhile lover, like Mr. Aldurfer, was a soldier at Fort Myer. Captain Foote, upon learning the reason for Flora's distress, promptly had the young soldier court-martialed.

Two years later Marcia Hopkins, a clerk in the Sixth Auditor's office of the Treasury Department, decided to end her woeful life by jumping from Aqueduct Bridge. She survived without a scratch and with a fresh attitude about life to boot. As recounted in the Post, she stated: "I must confess now that most of my trouble was fancied. I thought the devil was after me, and would only be satisfied when I was dead, but I am rid of him forever. God came to my rescue, and life is as sweet to me now as when I was a little girl, romping about without a care of any kind."

Jerry McCoy tells the story of the unfortunate DC cop, John Jacob Smith, who was assigned to the Aqueduct Bridge on the 4th of July in 1904. A group of carousing soldiers from Fort Myer (apparently an endless source of Aqueduct Bridge antics) were headed into Georgetown to celebrate that evening and stopped near the Georgetown end of the bridge, blocking others from passing. Officer Smith tried to get them to move on, but one of the soldiers, 23-year-old Samuel R. Young, took out his pistol and shot the officer several times in the abdomen. Young thought he was just being mischievous because his gun was loaded only with blanks. The blanks were nonetheless powerful enough to fatally wound Officer Smith, who died after surgery several days later. Smith was only the 7th DC police officer killed in the line of duty.

Needless to say, the bridge that was hosting all of this drama posed a number of safety issues. Since the 1890s, officials had worried that the bridge was too narrow and rickety for the traffic it carried. After the flood of 1889, some of the piers seemed to be deteriorating, and in 1903 an expensive two-year effort began to replace one of them. Other piers were repaired in subsequent years. According to the Baltimore Sun, the District's commissioners argued as early as 1902 that a more attractive stone arch bridge should be built in its place. Congress finally acted in 1916, authorizing the construction of a replacement bridge, and the Army Corps of Engineers began work on the Key Bridge in 1917.

|

| Ice on the Potomac above Aqueduct Bridge, February 1918 (Source: Library of Congress). |

The following year saw a major flood, the largest since 1889. “Destruction of the Aqueduct Bridge and all property along the entire Georgetown waterfront is imminent,” warned the Post on Valentine’s Day. The sense of foreboding was only slightly exaggerated. The thickest ice in years had formed upriver and was suddenly broken up by rising water on February 13, sending huge cakes of ice on fast-moving floodwaters towards the bridge and Georgetown. The next day the water level at Georgetown was 16 feet above normal, shore-side boathouses and other structures were ruined, and the Army closed the bridge and set about dynamiting the ice floes that were piling up against its piers. By the 18th, however, the worst danger had passed, and the ice became more entertainment than a threat. According to the Post, some 30,000 gawkers were out on the bridge or on nearby roads marveling at the spectacle. “Ain’t it wonderful what nature can do!” one young woman exclaimed. The Post’s jaded reporter was singularly unimpressed: “Every once in awhile some spectator would become hypnotized by the sight of a particular piece of ice. You could tell when the ice had gripped his attention by the slightly idiotic smile that played over his features…” Policemen and soldiers were kept busy throughout the day trying to keep such people moving along the narrow bridge.

|

| Postcard view of the new Key Bridge before the Aqueduct Bridge was removed (Author's collection). |

After the new Key Bridge opened to traffic in 1923, the old one, now cut off from traffic at both ends, stood wasting away in the river for ten years. Congress had stipulated that it be removed but hadn't provided any funds to do so. The Depression-era Civil Works Administration finally supervised the removal of the bridge's iron superstructure in 1933, although the old stone piers remained in place. It wasn't until 1962 that the Army Corps of Engineers removed the tops of the piers to facilitate boat racing on the river. The large stone abutment on the Georgetown side was left in place, as was one pier close to the Virginia side. The stumps of the rest of the original stone piers, so painstakingly constructed in the 1830s, remain to this day 12 feet below the low-water mark, presumably never to be seen again.

Sources for this article included: Gary A. Burch and Steven M. Pennington, eds., Civil Engineering Landmarks of the Nation's Capital (1982); Benjamin Franklin Cooling III and Walton H. Owen II, Mr. Lincoln's Forts (2010); D.C. Department of Highways, Washington's Bridges Historic and Modern (1956); Historic American Buildings Survey, Potomac Aqueduct (HABS DC-166); James M. Goode, Capital Losses (2003); Robert C. Horne, "Bridges Across the Potomac" in Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol. 53/56 (1956); Vincent Lee-Thorp, Washington Engineered (2006); Donald Beekman Myer, Bridges and the City of Washington (1974); Pamela Scott, Capital Engineers (2005); and numerous newspaper articles.

|

| The Aqueduct Bridge's Georgetown abutment (Photo by the author). |

* * * * *

Sources for this article included: Gary A. Burch and Steven M. Pennington, eds., Civil Engineering Landmarks of the Nation's Capital (1982); Benjamin Franklin Cooling III and Walton H. Owen II, Mr. Lincoln's Forts (2010); D.C. Department of Highways, Washington's Bridges Historic and Modern (1956); Historic American Buildings Survey, Potomac Aqueduct (HABS DC-166); James M. Goode, Capital Losses (2003); Robert C. Horne, "Bridges Across the Potomac" in Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol. 53/56 (1956); Vincent Lee-Thorp, Washington Engineered (2006); Donald Beekman Myer, Bridges and the City of Washington (1974); Pamela Scott, Capital Engineers (2005); and numerous newspaper articles.

+1.jpg)

John,

ReplyDeleteYour last photo of the Aqueduct Bridge's abutment as it appears today illustrates well the lost opportunity that the National Park Service has in not engaging and teaching visitors about this incredible 19th century engineering feat. I was reminded of the Aqueduct Bridge last moth as I walked NYC's High Line, a former elevated train freight line converted into a public park. Certainly it would not take much money to fill in the basin of the bridge and install fencing along the top of the stone wall that reproduces the surviving 19th century fence (the few pieces that have not been stolen yet). A bench could then be placed at the end of the abutment so visitors can sit and enjoy an unparalleled view of the Potomac River. A perfect use of this structure. Nah, that's why it will never happen.

I shared your post with my colleagues at the Potomac Boat Club - very popular! (Those are our flags that you see over the top of the aqueduct in the last photo.) The post card view of Key Bridge before the aqueduct was removed, while a bit fuzzy, shows that there were a number of boathouses on the Georgetown shore. We know that Dempsey's burned down in the 60s (located just upstream from the aqueduct) but not much more...Thanks for this.

ReplyDeleteAs a former NPS park ranger on the George Washington Memorial Parkway, I can state with fact that the Aqueduct bridge and its history was included in all of our rangers' "Theodore Roosevelt Island Safari" tours to visitors who attended the program at Theodore Roosevelt Island.

ReplyDeleteCate,

ReplyDeleteThat's good to know but I think you'll agree that more people see and walk past the abutment on the Georgetown side than across the river!

Thanks for clarifying that this aqueduct has nothing to do with getting drinking water from NW Washington to the rest of the city--I just couldn't make the pictures fit that story!! Wonderful account.

ReplyDelete