Two hundred years ago, long before it was urbanized, much of the District was either forest or farmland, and much of the farmland produced grain—commonly wheat, rye, and corn. Farmers needed mills to turn that grain into flour, both for their own use and to sell at market. To serve these farmers a string of mills once lined the shores of Rock Creek, using the age-old clean power source of the creek's water to turn their lumbering grindstones.

|

| Peirce Mill viewed from creek side, before installation of the new water wheel and chase (photo by the author). |

These "custom" mills each served their local farm communities. There were the twin mills—Argyle and Blagden—on either side of the creek just north of where Broad Branch Road intersects with Beach Drive. The Adams Mill, on land now part of the National Zoo, was acquired by John Quincy Adams in 1823; it was originally called the Columbia Mill. Further south, just above Georgetown, was Lyon's Mill, an impressive structure that had two waterwheels, one on each end of the building, to increase production. The National Park Service erected rarely-noticed historical markers at the sites of each of these industrial dynamos, and there were at least half a dozen more along the creek as well. They're all gone now save for one,

Peirce Mill, which now once again grinds corn into meal.

Peirce Mill, on Tilden Street close to Beach Drive, was built by Isaac Peirce (1756-1841), a Quaker farmer from Pennsylvania who had moved to the Washington area in the mid 1780s and in 1794 acquired a vast 160-acre tract of property along Rock Creek. The property, which originally stretched to the Maryland border, included an earlier mill that Peirce replaced with the current one in about 1820. Working with his stonemason son, Abner (1785-1851), Peirce constructed a simple but very sturdy building out of blue granite quarried from the nearby hills. The mill structure was just one of several buildings in the Peirce farm complex that survive to this day, including an adjacent carriage house, a distillery across the road (now a private residence), and a small spring house just up the hill to the west, the oldest of these structures.

|

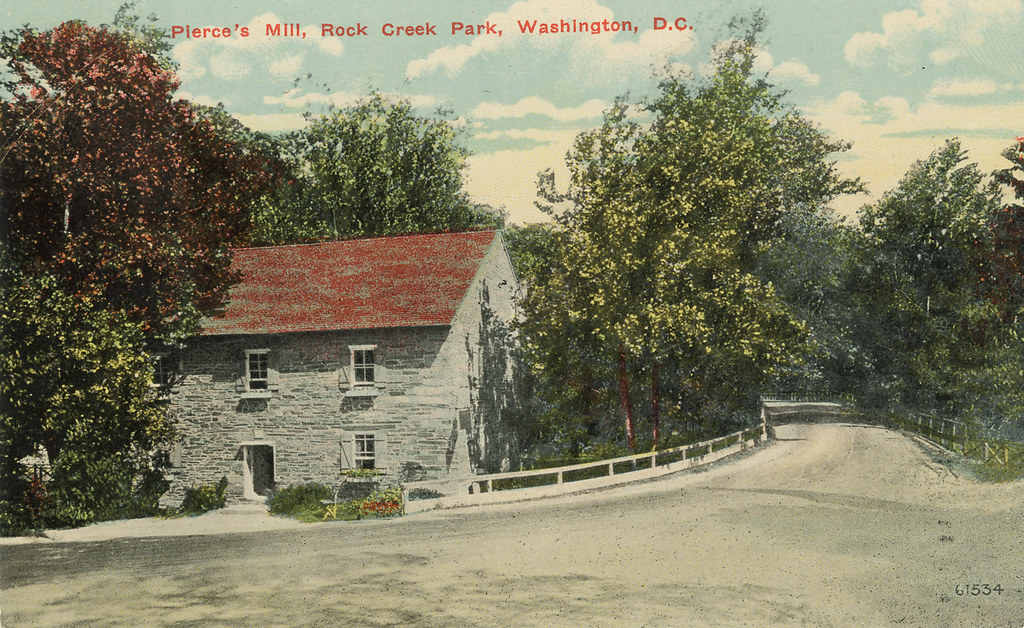

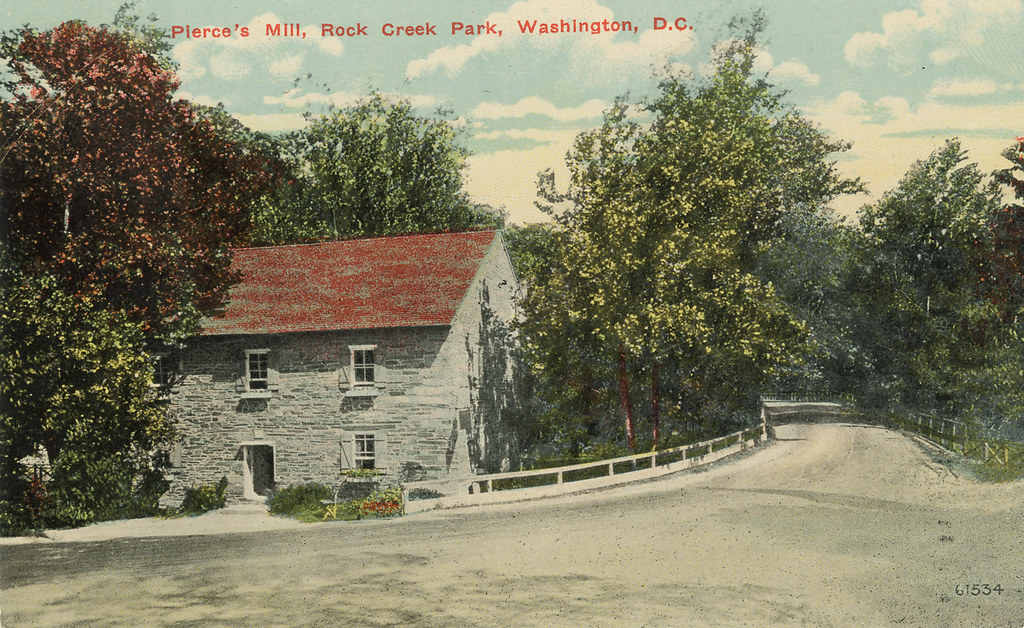

| Postcard view of the mill from around 1910. |

Peirce (yes, that's the way he spelled it) was a millwright—he built and owned his mill—but he didn't operate it. He hired millers to do the hard work of actually milling grain. And hard work it was. Traditionally, grist mills used their waterwheels solely to turn the millstones, also known as buhrs. Everything else was done by hand, including loading the hoppers that served grain to the buhrs, carrying the ground meal to the top floor of the mill to dry, scooping up the dried meal and filtering it into sifters, and finally filling barrels with the finished flour. In 1795, an inventor from Delaware,

Oliver Evans (1755-1819), published

The Young Mill-Wright & Miller's Guide, in which he described a complete system he had perfected for automating the functions of a flour mill. He turned the interior of the mill into an elaborate Rube Goldberg contraption of wooden cogs, chutes, elevators, hoppers, and bins, all powered by the mill's waterwheel. His patented system, producing superior flour with dramatically less labor, was first used on a large scale at the Patapsco Mills in nearby Ellicott City, Maryland. Isaac Peirce likely also used Evans' system to outfit his own mill.

Peirce Mill now is being restored with an historically accurate Evans-type automated system, which is a wonder to behold when all the machinery clatters to life. Powerful wooden gears connect the main horizontal shaft from the waterwheel at the basement level to a vertical shaft that extends up four stories to the attic level, driving all the other mechanisms. The millstones grind grain on the first floor, after which an elevator (a vertical conveyor belt of little wooden buckets) carries the flour up to the third-floor grain cleaner and hopper boy, where it begins the drying, cleaning, and sifting process that takes it through the bolter on the second-floor and finally down to storage bins on the first.

While some resisted Evans' inventions, others soon adopted them, often infringing Evans' patents. Despite the revolutionary implications of his inventions, Evans was not widely celebrated. As Steve Dryden points out in his indispensable

Peirce Mill: Two Hundred Years in the Nation's Capital, Evans was not well-liked and was called a "pompous blockhead" among other things. After he successfully lobbied Congress to reinstate his expired patents, he incurred the wrath of none other than Thomas Jefferson, who had built an Evans-type mill at Monticello and who wrote to Congress that Evans' devices "are too valuable for anyone to be permitted to control them." Another letter Jefferson wrote in 1813 about his vexation with Evans' reinstated patents has become a classic text on the limits of intellectual property rights.

|

| Diagram of the mill's operations (drawing by Ted Hazen, courtesy of the National Park Service). |

Meanwhile, Isaac Peirce's mill prospered through nearly the entire 19th century. After Peirce's death in 1841, the mill was taken over by his son Abner, who died ten years later. Abner left the mill to his nephew, Pierce Shoemaker (1816-1891), who owned it until his death, after which it was bought by the government to be part of the new national park known as Rock Creek Park. Peirce and his successors seem to have been well attuned to advances in technology, investing in high quality millstones and changing the type of waterwheel the mill used at least twice. And business was good. Shoemaker's son Louis recalled that in the 1870s "[i]t was a daily occurrence to see from ten to twelve teams and a number of boys on horseback from the surrounding country with grist," waiting at Peirce Mill to have their grain turned into flour.

But technological advances—cheaper, more efficient steam power—quickly made water-powered mills obsolete in the mid 19th century, and by the 1880s, the mills along Rock Creek all were closing down. The end of the road came without warning for Peirce Mill one day in 1897, when the mill's main shaft broke in the middle of grinding a load of rye for a local farmer. Miller Alcibiades P. White remarked that "the neighbor had to haul his unground rye away, and I guess he never got it ground. That was the last time the mill operated."

From that point forward, Peirce Mill was destined to take on a new life as an icon of the rustic past. Even before it ceased operations, Peirce Mill and its grounds were used as a getaway from city life. In 1903 an "elderly dame who resides in the northern part of the city" reminisced in

The Washington Times about the romance of an outing to Peirce Mill:

I remember well the first picnic I ever attended escorted by a young gentleman. It was given at old Pierce Mill. Many of the young people rode out in one of Naylor's omnibuses and others had the good fortune to be invited by some young man who had a buggy. It was as pretty a September day as ever dawned, and we all knew each other and had a lovely time. I recollect we danced on the second floor of the mill, and I felt as if I was the belle of the ball. When the great big full moon came up that night all the boys and all the girls fell in love, and many tender words were said and vows pledged only to be broken that beautiful September night. I remember I rode out with one young man and came home escorted by another, and made all the girls jealous, and that was glory enough for me.

|

| Postcard view of the Pierce Mill dam, constructed in 1903 (author's collection). |

While there was talk as early as 1907 of acquiring a new waterwheel and getting the mill running again, nothing was ever done about it. The water to power the mill had been supplied through a millrace—a small channel dug parallel to the creek from a point upstream where a rocky dam diverted water into it. The millrace had been filled in some time after the mill ceased operating, making it difficult for an observer to figure out how the mill had gotten water to power its wheel. Another wholly inappropriate touch was the construction in 1903 of a decorative dam adjacent to the mill. The dam, which is still there, is certainly very attractive, but it added to visitors' confusion in trying to understand how the mill wheel worked.

Not that there was any mill wheel left at that point. In 1906, a large enclosed porch was built alongside the mill where the wheel had been, and the Peirce Mill Tea House made its debut. Visitors to the picturesque old mill could purchase "ices and soft drinks, tea and sandwiches and cake from 2 o'clock onward each day" to enjoy on the new porch. The tea house became very popular. In 1912, the

Aberdeen American noted that the mill "is a favorite resort where President Taft and members of Washington's smart set often stop and sip tea. It is a fashionable rendezvous for horseback and motor parties and many elaborate social functions are held at the old mill."

Over its 30-year existence, the tea house had a number of proprietors, including Hattie L. Sewell, an African-American, who took over in 1920 and reportedly offered good service and increased business. She unfortunately ran afoul of an influential neighbor, E.S. Newman, who complained that with Sewell there the mill would become "a rendezvous for colored people, soon developing into a nuisance." It was certainly a very low point in the mill's history when Sewell was forced out after only one year in business.

The tea house closed in 1934 when Secretary of the Interior

Harold Ickes (1874-1952) endorsed a Works Progress Administration project to restore the mill to working order after almost 40 years of dormancy. Architect Thomas T. Waterman (1900-1951), who would later lead the restoration of

Decatur House, supervised the work, which aimed to preserve a sense of the mill's long history and evolution, rather than attempting to recreate a specific moment in time. The Fitz Water Wheel Company of Hanover, Pennsylvania, was entrusted with reconstructing the Oliver Evans-type milling mechanisms. Since no records existed of the mill's original machinery, the reconstruction was of a typical system that would have been installed in a mill of this type.

On a rainy day in January 1937, some 2,600 curious visitors lined up under umbrellas for their turn to catch a glimpse of the old mill in action on the day it re-opened. White-haired miller Robert Little, who had grown up working in a flour mill, was busy keeping the mill running, poking at the little elevator buckets that carried meal to the top floor, keeping them from getting stuck. Little estimated that he could produce ten barrels of flour a day if the mill ran for eight hours. You could buy a five-pound sack of meal from him for 25 cents—a good deal, considering it was stone-ground. Flour was also sold to government-operated cafeterias, with the idea that the sales would support the mill's operations.

|

| Peirce Mill in early 1940. Photograph by National Park Service photographer Abbie Rowe. |

It turned out to be harder than the Park Service had imagined to keep the mill running, however. The mill operated only during the colder months because there was no means for preserving flour in the heat, but the mill wheel would dry out during the off season, and eventually it warped and cracked. Other problems with machinery and an unreliable water supply led the Park Service to shut the mill down in 1958. As Steve Dryden explains, it took until 1970 to get the mill running again, and several modifications were made in the name of expediency that were ill-advised. For example, the old millrace that drew water from the creek was abandoned altogether, and instead water was pumped in from the city's chlorinated municipal supply. At least the mill was running again.

Despite the starting and stopping of operations, Peirce Mill was a popular destination in Rock Creek Park, especially for groups of schoolchildren. In 1971, the Peirce carriage house, located next to the mill, was rehabilitated by the Park Service and rechristened the Art Barn, a showcase for local artists. Popular with local art aficionados as well as schoolchildren, who were offered free art classes, the Art Barn continued for some 21 years, until budget cuts shut it down. In 1992,

The Washington Post reported that the Art Barn had also been serving a secret mission. Unbeknownst to almost everybody, government agents had installed electronic surveillance gear in the attic of the Art Barn to spy on the nearby Eastern Bloc embassies of Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The Art Barn's director, Ann Rushforth, was quoted as saying, "We always knew which guys were the CIA guys because they always wore sunglasses indoors, had real sharp creases in their pants, short haircuts and shiny shoes." The agents, who were more likely from the FBI, ended their spy games as the Cold War drew to a close.

|

| The carriage house, formerly the Art Barn (photo by the author). |

Meanwhile, mill operations had stopped again in 1981 for more "make-do" repairs and then resumed several years later. Finally in 1993 the main shaft from the waterwheel broke as a result of decay, and it was clear that the mill could not operate again without a comprehensive restoration effort. Richard Abbott, an engineer who had volunteered at the mill when it was still working, organized a group, called the Friends of Peirce Mill, to get the mill operating again. This time, a careful assessment was made of the condition of the structure and its equipment, and an extensive multi-phased effort was begun to repair the mill. First, much work had to be done to the building itself to repair decayed structural elements. The milling machinery also needed extensive repairs and replacements, and finally a better water supply system had to be devised. A lot of work was accomplished over many years through private contributions, and then this summer extensive renovations and re-landscaping of the property around the mill was completed using funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. A grand re-opening of the beautifully restored mill took place on October 15, 2011.

To learn more about the mill's history, read Steve Dryden's excellent

Peirce Mill: Two Hundred Years in the Nation's Capital (2009). In addition to that, other sources for this article included William Bushong and Piera M. Weiss, "Rock Creek Park: Emerald of the Capital City" in

Washington History, Vol. 2, No. 2; Allen C. Clark, "The Old Mills" in

Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol. 31-32; Barry Mackintosh,

Rock Creek Park: An Administrative History (1985); Herman Steen,

Flour Milling in America (1963); listings for Peirce Mill in the

National Register of Historic Places and the

Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service brochures about Peirce Mill, and numerous newspaper articles.

I stopped by here today and was surprised to see that all the parking on the side of the street that the mill is on had been removed (except for two handicapped spaces).

ReplyDeleteYes, they replaced the parking lot with just a spot for loading/unloading school buses up by the carriage house. My understanding is that the old layout with the parking lot led to drainage problems--flooding in the mill. Thus the decision was made to restore the landscape to something approximating its historical contours to mitigate the flooding hazard.

ReplyDeleteThis was a really interesting article, I'll have to drive down some day and take a look. If you ever head over to the Eastern shore, the old Wye Mill in Wye, MD (http://www.oldwyemill.org/) operates with the same Evans system machinery and it's awesome to see when it runs. Evans really had an amazing imagination and mechanical skills to get something like this going in the time period that he lived in.

ReplyDeleteMount Vernon operates Evans system as well.

ReplyDeletei was just there today. it is beautiful. There is a rain garden built into the sloping place in the hill to help with stormwater runoff ("rain garden" is a prettier term than the actuality, which is a utilitarian feature, but it is nicely done).

ReplyDeleteDoes anyone know what, if any, plans there are for the Art Barn? It was shuttered today.

Great post. I have never been to this place but I want to go. It looks good. How big of barn to they use for grain storage millwrights repair?

ReplyDelete