She's a grand old lady, an exquisite neoclassical landmark, and Washington's first all-marble building. But the old General Post Office between 7th, 8th, E, and F Streets NW, nevertheless is not well-known and hasn't gotten the attention it deserves. It is now leased out as a boutique hotel because the government couldn't summon the wherewithal in the 1980s to commit to a more distinguished use.

|

| The General Post Office building today (Photo by the author). |

Before the General Post Office was here, this site was the location of Blodget's Hotel, the largest privately-owned structure in Washington until the federal government bought it in 1810. Of course, there wasn't much competition in those days. Samuel Blodget, Jr. (1757-1814), a native of Massachusetts, had become a merchant and grown rich in the 1780s through trade with the East India Company. By the 1790s, he was infectiously enthusiastic about prospects for the new capital city and began hatching schemes to make boatloads of money in Washington real estate. Blodget's reputation, as Fergus Bordewich explains, was as "a man of big ideas, a sort of Donald Trump of the 1790s, a man who

got things done." Thus he was able to get George Washington and other important people to go along with his hare-brained scheme of running a lottery to finance construction of the capital city. The grand prize in the lottery would be a magnificent hotel, worth $50,000, that he would construct at a prime location. Blodget's Hotel, designed by

James Hoban (1758-1831), architect of the White House, was indeed built on this location, but the lottery to finance it was a dismal failure. Blodget lost everything in the process and died impoverished in Baltimore in 1814. Meanwhile, his hotel, begun in 1793, was eventually completed in 1810 and taken over by the government for office space, primarily the Patent Office.

Four years later, the country was at war with Britain, and Washington came under direct attack. The British occupied the city, burning public buildings, including the Capitol and White House. They had set their sights on Blodget's Hotel as well and were about to set it on fire, when

William Thornton (1759-1828), head of the Patent Office, intervened. Thornton's exact words to the officer commanding the British were not recorded, but he apparently argued that the patent records housed in the building were private property and thus not fair targets for the British. One story has it that he claimed that destroying these patent records would be the equivalent of burning down the great Library of Alexandria, a devastating crime against civilization. Whatever his argument, the British apparently were duly convinced that patents are important, and they spared Blodget's Hotel. After they were gone, it was the only substantial public building still standing, so Congress met there for about a year while the Capitol was being reconstructed. Then, in December 1836, a servant accidentally dumped hot fireplace ashes into a wooden refuse box, setting the building on fire. It burned to the ground, destroying thousands of patent models and records. Civilization seems to have survived the devastating setback, although now a new, larger, and—most importantly—

fireproof building was desperately needed.

The new, fireproof General Post Office building to arise on this site was part of a mini-boom in government office construction that got underway in the Jackson administration. In addition to this one, two other major building projects were initiated: the Treasury Department building on 15th Street NW near the White House and the new Patent Office building in the block just north of this site.

Robert Mills (1781-1855) designed two of them (the Treasury and Post Office buildings) and supervised construction of all three. The General Post Office, begun in 1839, was the last of the three to get underway.

|

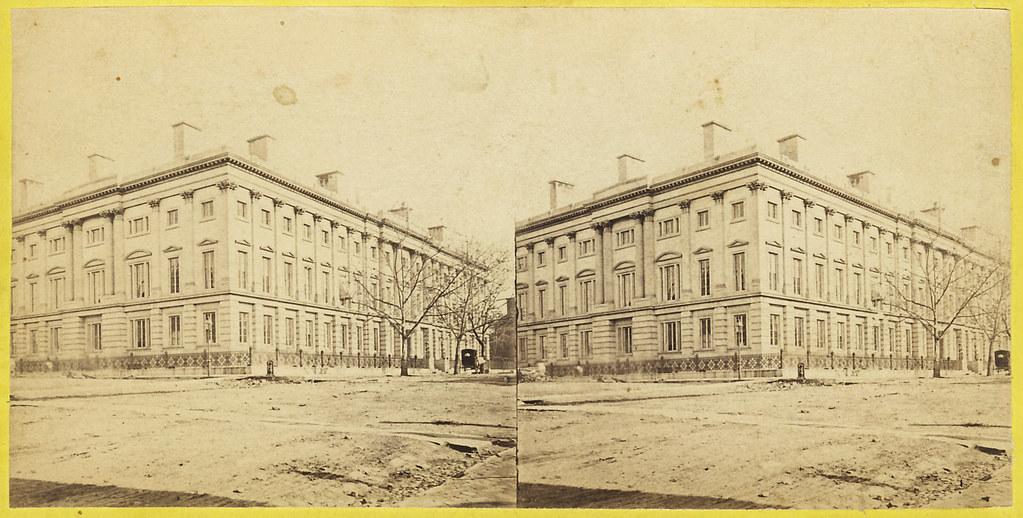

| The E Street facade c. 1870, before street grading (collection of the author). |

|

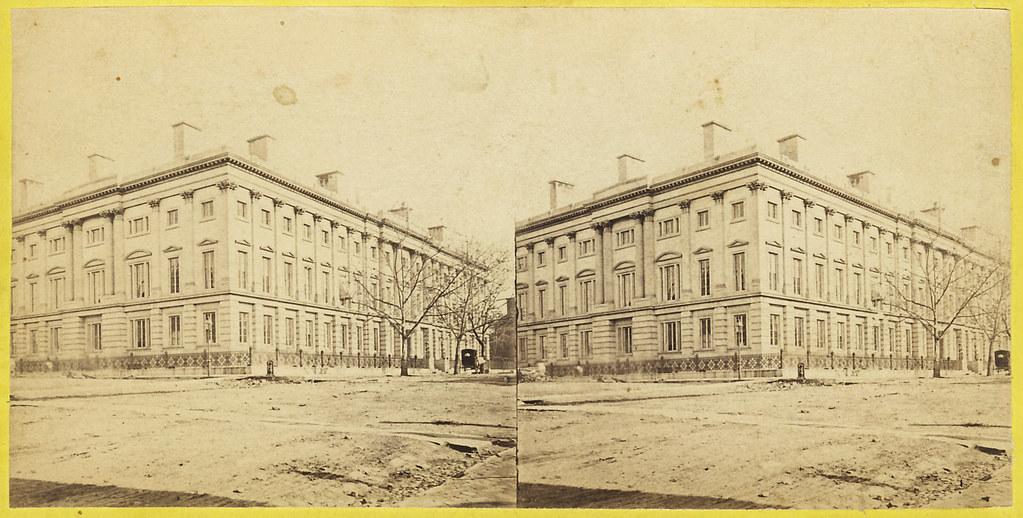

| An 1870s view of the F Street side (collection of the author). |

|

| The original E Street facade today (Photo by the author). |

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Mills was one of America's first professional architects, learning his trade from James Hoban and

Benjamin Latrobe (1764-1820). He designed many public buildings but is probably best known as the architect of the Washington Monument. While his works were admired by some, he also had many detractors, especially among his rivals. After construction of the Treasury and Patent Office was well underway, a change for the worse in the economy prompted a Congressional inquiry into the ongoing federal construction projects, which suddenly were portrayed as extravagant and wasteful. Mills came in for all sorts of criticism, most of it unfair. John Quincy Adams, then in the House of Representatives and sympathetic to the criticism, referred to Mills in his journal as a "wretched bungler in architecture." A bill to tear down the half-built Treasury building and start all over with a new design was narrowly defeated. Mills continued with all three projects, but his reputation had been hurt, and he received few federal commissions after these were completed.

The completed Post Office building contrasts strikingly with its neighbor, the Patent Office, despite the fact that they share a neoclassical vocabulary. Finished in sandstone, the central portico of the Patent Office has heavy Doric columns that give it a brawny, imperious look. In contrast, Mills' Post Office, with its white New York marble finish and Italian Renaissance styling, is more delicate and refined. In keeping with Palladian antecedents, engaged Corinthian columns and colonettes elegantly define the upper floors and set them off from the rusticated ground floor. Mills considered this his masterpiece, and many of his contemporaries agreed. An article in the December 1859

Harper's New Monthly Magazine states: "We doubt if there is a building in the world more chaste and architecturally perfect than the General Post-Office as now completed. Without the imposing grandeur of its neighbor the Patent-Office, it is so symmetrical, and the details so faithfully executed, that it carries us back to the palmy days of Italian art." While this must have been one of the last moments in history when architectural chasteness was widely celebrated, the building indeed is as graceful as it is stately.

Mills designed the southern half of the current building. Built between 1839 and 1842, it fills the E Street side of the block and extends part way up 7th and 8th Streets. Inside Mills used fireproof construction techniques he had been perfecting throughout his career, including solid masonry construction with vaulted ceilings and marble-tiled floors, the same durable and utilitarian scheme employed in the Treasury and Patent Office buildings. Noteworthy are two elegant spiral staircases with ornamental cast-iron balustrades set in domed, sky-lit alcoves. The first public telegraph office was opened in this building by Samuel F.B. Morse in 1845.

|

| Photo by the author. |

Beginning in 1855, the U-shaped building was extended and connected along F Street to form a complete rectangle filling the block. The extension's architect was

Thomas Ustick Walter (1804-1887), a fierce rival of Mills who inexplicably let pass the opportunity to negate or overpower the original design and instead created a very sympathetic and respectful extension. The Walter addition is not noticeably a different building, especially on the outside, where the new, white marble from Cockeysville, Maryland, blends in well with the original marble from Westchester, New York. Walter added more pronounced Corinthian columns, including a full portico with freestanding columns on the north (F Street) facade. Inside Walter used iron bars to support upper stories; ceilings are coffered rather than vaulted, as in the original section. The new section also had steam heating, thus dispensing with the many chimneys so prominent on the roof of the southern part.

Around 1873, the streets in this area were graded down, with the result that the building's ground floor ended up higher than the street. The plain walls of the basement, which had been hidden in light wells, have been exposed ever since, disrupting the symmetry of Robert Mills' original design.

The General Post Office (i.e., the Post Office Department) occupied the building for most of the 19th century, until new quarters in an ostentatious Romanesque Revival building on Pennsylvania Avenue were completed in 1897. The General Land Office then took over until World War I. General John J. Pershing, commander of American Expeditionary Forces in Europe had offices here in 1919, when he was working on his final report.

After Pershing departed in 1921, the building was shared by several government agencies, including the U.S. Tariff Commission, which eventually took over almost the entire building. In 1974, the Tariff Commission became the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC).

|

| In this 1920s postcard view of F Street NW, the General Post Office building is on the left and the Patent Office Building on the right. |

|

| The same view today (Photo by the author). |

After decades of residence in the building, the ITC found by the 1980s that its quarters were getting a tad run-down. As reported by Stuart Auerbach in

The Washington Post, the ITC's chairman testified before the Senate Finance Committee in March 1983 that the

General Services Administration (GSA) didn't seem to care about restoring the building, instead just waiting to turn it over to the

Smithsonian Institution and let them worry about it. Deferred maintenance had resulted in a leaking roof, falling plaster, loose window frames, inadequate plumbing, and—perhaps most vividly—exploding rodents.

GSA was using a poison that makes rats drink so much that their insides burst. It was supposed to drive the animals out of the building, but there was so much standing water from leaks that the hapless little beasts (some reported to be "as big as cats") didn't need to leave. The results were undoubtedly unpleasant for all involved. Dead mice and rats were encountered on a daily basis; even one of the commissioners encountered a dead mouse in her office one day.

GSA countered that it had been trying to find a new home for the ITC for several years, but that the ITC had been uncooperative. GSA then offered the ITC space in the hideous Bicentennial Building, constructed in 1976 at 600 E Street, NW. The ITC refused. GSA insisted. On and on it went.

Meanwhile, the Smithsonian presented its plans for the building, hoping to use it to expand the museums housed across the street in the old Patent Office building. The plans called for devoting the Patent Office space to permanent exhibits while using the Old Post Office for temporary exhibits, plus a sculpture garden in the central courtyard. The Smithsonian wanted GSA to simply hand over the building for this use, but GSA insisted the Smithsonian pay fair market value for the structure, money it didn't have.

The stalemate dragged on for years, while the building itself continued to suffer. At some point wires had been strung on window ledges in a misguided scheme to keep birds away. The wires were clipped to the surface through numerous holes drilled in the marble. The drill holes allowed water to seep into the marble and cause erosion. In 1984, the

Post reported the GSA Commissioner of Public Buildings as saying "I acknowledge that the maintenance of this valuable and historic property has not been performed in an acceptable manner. The lack of proper attention to preservation and restoration of this building...is inexcusable."

While the ITC finally left the building for new quarters at 500 E Street SW in 1988, the Smithsonian, despite being given the old building by Congress, was never able to come up with the funds for renovating it. Instead, the building sat empty for another decade, with GSA unable to find a federal tenant interested in a relatively small space that required major repairs and restoration. Finally, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1927-2003) convinced the Smithsonian that its best option would be to lease the building for commercial use for, say, 40 years, hoping that funds would be more readily available for museum purposes at a later date. According to the

Post, Moynihan pushed for this solution after discovering that the boarded-up building was being used as a crack house.

GSA ran a competition, which the

Kimpton Hotel and Restaurant Group won. The government spent about $4 million to fix up the exterior of the building, while Kimpton converted the interior into a 184-room boutique hotel through a lengthy and elaborate process of renovation and negotiated restoration. The new Hotel Monaco, with a 60-year lease, opened in 2002. Benjamin Forgey, the

Post's longtime architecture critic, commented that "it is unsettling to see one of the city's most distinctive public buildings transferred to the private sector. It remains extremely regrettable that the Smithsonian let slip a long-standing opportunity to turn the building into a public museum." However, he concluded that "The Monaco project is an exemplary, unambiguous reminder of what creative preservation can do for a building, and, potentially, for a city." After 8 years of successful operation, the hotel is now an established fixture in DC's Penn Quarter.

Sources for this article included: Fergus M. Bordewich,

Washington: The Making of the American Capital (2008); Gordon S. Brown,

Incidental Architect: William Thornton and the Cultural Life of Early Washington, D.C., 1794-1828 (2009); John M. Bryan,

Robert Mills: America's First Architect (2001); James M. Goode,

Capital Losses (2003);

Harper's New Monthly Magazine (December 1859); Pamela Scott and Antoinette J. Lee,

Buildings of the District of Columbia (1993). Numerous newspaper articles as well as listings in the

Historic American Buildings Survey and

National Register of Historic Places were also consulted.

amazing how the view has not changed in the last two pics

ReplyDeleteI heard the Hotel Monaco was haunted?

ReplyDeleteYes

DeleteAny building that has been around as long as this one is sure to have ghost stories associated with it, though I haven't heard any myself. The Old Post Office on Pennsylvania Avenue, where the Post Office Department moved in 1897, certainly has its share of stories about elevators moving on their own and bells spontaneously ringing. -Has anyone heard a ghost story about this building?

ReplyDeleteThank you for another great article. I live downtown and love reading about the buildings I see every day.

ReplyDeleteHave you ever thought of doing a sort of neighborhood summary piece? I pass so many buildings with traces of past occupants, like the word "EQUITABLE" or an interesting logo, or the appearance of perhaps once having been a fire house, and wonder who used to be there. I suppose most of the buildings wouldn't give enough history for a whole post on each one, so maybe tackle a block at a time?

Yeah John...tackle a block at a time!

ReplyDeleteSome of my earlier posts covered multiple buildings seen in a single postcard view. I may do some more of those, although I get the impression that many people like the more in-depth portraits of specific places. There's certainly a tradeoff to be made...

ReplyDeleteA well done post! I grew up in Washington and am familiar with its buildings. I never tire of reading about them and seeing pictures of the street-scape. Many thanks for your research and insights.

ReplyDelete