The Sterling Hotel, originally the Hotel Johnson, once stood on the southeast corner of 13th and E Streets, NW, a corner that now fronts on Freedom Plaza and is just north of Pennsylvania Avenue. This was never one of Washington's great hostelry's, but it was listed as one of the 30 "principal hotels" of Washington in Rand McNally's

Pictorial Guide to the City of Washington from 1913. It must have hosted many a colorful character in its day. After the hotel was torn down in late 1932, an anonymous columnist in

The Washington Post who went by the pen name of "The Stroller" remarked that "All that's left of the notorious old Sterling Hotel, at Thirteenth and Pennsylvania, is the doorway..." Notorious? -No further explanation is provided.

There's no question that the larger neighborhood had been notorious indeed in the19th century. The stretch of Pennsylvania Avenue/E Street between 13th and 14th Streets in civil war days was known as Rum Row for its many saloons and gambling houses. Apparently the cops generally turned a blind eye to all the illicit activity that went on around here, at least until they decided to crack down during the Grant administration. This was where George Parker made $4,000 a week running faro games in the rooms above Kidwell's drug store, later to become

Bassin's Restaurant. The drinking, of course, was as prolific as the gambling. Shoomaker's (known as "Shoo's"), a prominent saloon along this stretch, was famous as the place where the gin rickey was said to be have been invented to quench the thirst of Col. Joseph Rickey on a hot day in the 1880's.

|

| The site of the Sterling Hotel as it appears today. |

According to George Rothwell Brown in his 1930

Washington: A Not Too Serious History, a Boston prize fighter named Charlie Godfrey came to Washington and opened a saloon and gambling house on the future site of the Sterling Hotel at about the time of the civil war. His joint soon became "one of the most eagerly patronized of faro banks"—not that there weren't plenty of competitors. According to Brown, Godfrey's gambling house flourished there until some time in the 1870s, when the building was "remodeled" as a hotel.

|

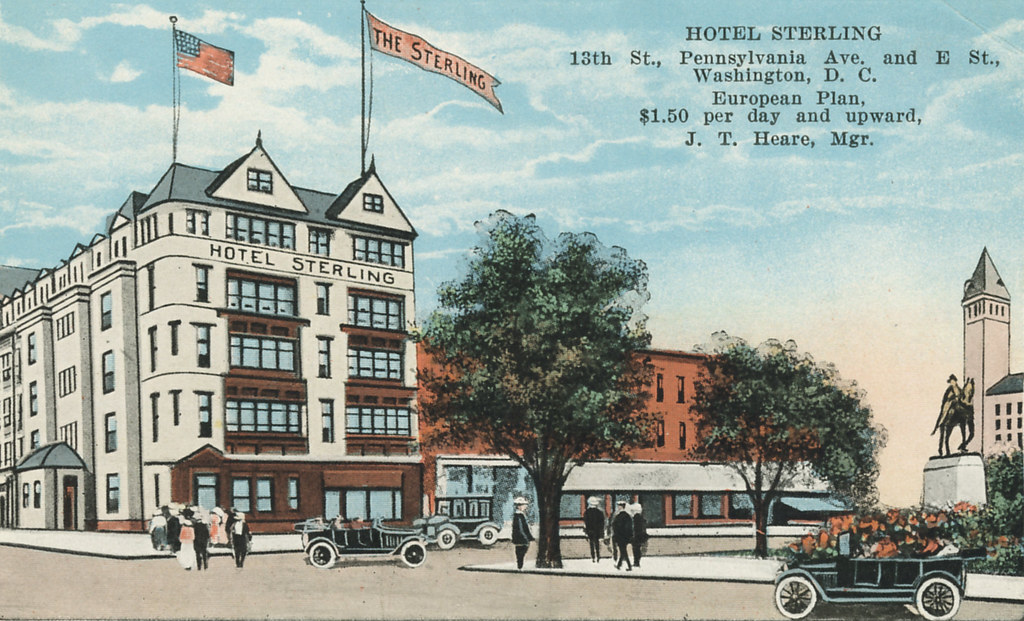

| Postcard view of the Hotel Sterling (Collection of Sally Berk). |

Until the 1890s, many people considered it bad luck to completely tear down an old building and replace it. Much better to connect existing buildings, add floors, redo the facade, etc. Thus almost all of the old Washington hotels—including

Brown's, the

National,

Ebbitt House, and the old Willard—were built up by combining and expanding existing structures. The Sterling was no exception. It began as the Hotel Johnson, founded and operated by Esau L. Johnson. It must have begun small, maybe as little more than a boardinghouse above a restaurant. Johnson expanded it in 1894 by leasing an adjacent newly-built hotel building (the "Adalinda") and again in 1901 by the purchase of other adjoining lots.

The newspapers occasionally reported unusual incidents at the Johnson: a cop, Robert Venneman, came in from his beat early one morning in 1894 and died suddenly from a heart attack while sitting in the hotel office...a young maid, May Hill, was caught stealing a silver whiskey flask from a guest's room in 1900 by "Detectives Brown and Lacy," who promptly hustled her off to the House of Detention...a fire flared up in the hotel's awnings in 1902 after someone tossed a cigar stub from an upper-floor window; it was quickly extinguished by the vigilant actions of the No. 1 Chemical Company...

In 1912, Johnson sold his five-story hotel to Charles Jacobsen for a reported $200,000. Jacobsen immediately began extensive renovations under the supervision of manager J.W. Gibson, who had been recruited from the

Shoreham. Improvements included broadening stairways and halls, adding an electric elevator, and establishing a large new lobby right at the corner of 13th and E. The dining room was refinished in red with indirect lighting, and a balcony was installed for an orchestra, "which will furnish music at the hours for serving lunch, dinner, and supper," according to the

Post. Also on the first floor was a "grill, the walls of which are covered with paintings of game and the chase" and on the second floor a parlor with a commanding view of Pennsylvania Avenue. At this point the hotel had 75 guest rooms, all newly papered, painted, and furnished, with private baths in 35 of them and "shower baths" in six. Each room had hot and cold water, electricity, and long-distance telephone service.

|

| The Sterling decorated for Woodrow Wilson's inauguration in March 1913 (Source: Library of Congress ) |

By this time, the old Rum Row had long since sobered up—at least to a degree—and was now known as Newspaper Row. The

Washington Post had built an impressive and whimsical Romanesque Revival headquarters building at 1337 E Street in 1893. This was followed by the imposing

Munsey Building in 1905, which housed the offices of the

Washington Times. Other national papers set up offices in the neighborhood as well.

Since the newly-refurbished Sterling was just down the block, the Post decided to make it the headquarters for a grand publicity event it staged in May 1913: a four-day "motor truck run." Trucks of all types were invited to enter the contest, which included a circuit that traversed towns in Maryland and Pennsylvania. Trucks, all loaded to capacity, left from E Street at one-minute intervals and followed a winding 288-mile course over "the worst hills that can be found within a few hundred miles of the National Capital...filled with 'thank-you-ma'ams,' bumpers, holes, and other faults of construction which would not be encountered in the ordinary course of business for a truck." It took four days for the trucks to complete the circuit and return to the starting point. Careful records were to be kept of any mechanical problems or expenses as well as how much fuel was used. The winner would be the one to return with the least amount of trouble and expense.

The grueling course apparently was designed in large part for propaganda purposes, at least in the minds of its designers: "Lined on all sides by some of the most prosperous farms in the Eastern States, the run afforded an opportunity to the farmers to see that the horse has been eliminated as a factor in the larger interests of the commercial age and that the motor truck age is well on its way." Of course, the

Post neglected to send a reporter to interview these farmers and hear what they actually thought of all these trucks rumbling through the countryside.

Entrants included Wilcoxes, Atterburys, and Whites; an Autocar, Hupmobile, Vulcan, Little Giant, McIntyre, and Witt-Will. The Vulcan won, with a cost per mile per ton of load of 0.0122 cents, and its proud owner was awarded a silver trophy at the Sterling Hotel. Many of the trucks performed very well, and the viability of truck transport—had it been in any doubt—was unequivocally put to rest.

|

| The winning Vulcan truck, from The Automobile, May 15, 1913, via Google Books |

After World War 1, a shift away from the Avenue began for well-to-do travelers. The Wardman Park Hotel over in Woodley Park opened in 1918, the Mayflower on Connecticut Avenue in 1925. Perhaps the Sterling grew seedy in the 1920s, or the nature of its clientele changed, and thus it became "notorious." In any event, in 1930 the hotel and an assortment of adjoining properties were sold to the Ford Motor Company, which intended to build "an immense building to be a credit to Washington and conforming architecturally to the Federal buildings on the south side of Pennsylvania Avenue," as reported in the

Post. Ford had previously operated a smaller final assembly plant at Pennsylvania Avenue and John Marshall Place. However, the Ford building was never constructed. Instead, after the old Sterling Hotel was razed in 1932, a "temporary" parking lot filled the site for 20 years. In 1953, builder John McShain constructed the Pennsylvania Building on the site, a typical 1950s office building with horizontal ribbons of green-tinted windows. The Pennsylvania Building remains standing today, although in 1987 it was rebuilt with a new more neoclassical facade that better fits with its large federal neighbors.

"Until the 1890s, many people considered it bad luck to completely tear down an old building and replace it."

ReplyDeleteA superstition that I wish today's society would subscribe to...

Amen, Yes indeed! I completely agree! It is sad the historical places lost to development these days!

DeleteI suspect there was no sobering up to transform Rum Row to Newspaper Row -- maybe the reporters just exchanged one ``office'' for another? And how cool would it before the WaPo to recreate the Motor Truck Run but instead make it a Monster Truck Run?

ReplyDelete