The Elegant Palais Royal Department Store

Many Washingtonians remember the Woodward & Lothrop department store, which used to be downtown at 11th and F Streets, N.W. However, much less well-known is its old rival, the Palais Royal, which was once located in the block immediately to the north, at 11th and G.

Under Lisner's leadership the store proved very profitable. Lisner emphasized low prices and operated a cash-only business when most other dry goods stores offered credit. The reputation for quality merchandise at a low price built sales steadily, although Lisner was not immune to missteps. One dramatic incident occurred in March 1880 when Lisner accused his head clerk, Annie M. Nixon, of stealing a pair of kid gloves. Lisner seems to have confronted Miss Nixon in front of customers and had her arrested. Not a good idea, as it turned out. The Washington Post, not yet by any means a world-class newspaper, reported that the police officer at the local precinct station declared the whole affair a "put-up job" and let Nixon go with a "small collateral" for her appearance in police court the next day. The Post also said it had interviewed Lisner, who "told a voluminous story with evident delight" about how he had suspected Nixon of stealing items from the shop and had instructed another employee, Issac Teeney, to watch her. Teeney had subsequently found the purloined gloves in Nixon's coat pocket. The problem, however, was that Nixon was "a pretty brunette" and Teeney an African-American porter. The police court quickly absolved Nixon the next day. Teeney was presumed to be lying--heck, he probably stole the gloves himself. As soon as Judge Snell pronounced his verdict there was "prolonged applause, which the bailiffs could not control, and the young lady was immediately the recipient of congratulations." Lisner, in contrast, was "already unfavorably regarded by the general public," according to the Post, and was now reviled (at least for the moment) for making such a false accusation about the pretty brunette. The next day the Post ran a piece entitled "Lisner's Abject Terror," in which it described how Lisner had summoned the police to his store after having his life threatened by a man who had come in off the street. Lisner asked the officer who arrived to stay and protect him, but the policemen insisted he had to keep to his beat. "'But,' said Lisner, 'what if I am killed?' 'Well,' coolly retorted the officer, 'then I will find your body.'" -Such was the life of a Jewish shopkeeper in 1880 Washington.

That incident was probably soon forgotten, but Lisner continued to face difficulties due to his poor health. In 1884 he took a trip to the spas at Carlsbad in what is now the Czech Republic, but he did not think it did any good. He returned to New York City deeply discouraged, and his brother George induced him to stay there awhile. One afternoon, Abram borrowed $10 from his sister-in-law and went out to a buy some ice cream for her children. He also bought a handgun. The New York Times reported that, after regaling the children with the ice cream, he went upstairs and shot himself twice in the back of the head. Fortunately, the attempt was not successful; Lisner recovered and soon returned to Washington.

By 1887, Lisner was renting out more and more of the Centennial Building, employing some 250 clerks and steadily expanding his business. The Washington Post described the merchandise in his newly-opened Silk Department:

Soon Lisner decided it was time for new, larger quarters. A general trend had already been underway in the early 1890s for merchants to move from flood-prone Pennsylvania Avenue up to higher ground along the F Street corridor, which was becoming the new commercial center of Washington. Lisner followed the trend—and pushed it a little—by choosing the site on 11th and G Streets for his new building, a block north of the established commercial drag. Lisner was confident he would do well there, and he did.

The Palais Royal building, completed in 1893 at a cost of $250,000, was designed by Washington architect Harvey L. Page in the Chicago style, a practical design vocabulary for high-rise commercial buildings that stressed large windows and restrained neoclassical trim. The building was similar to Woodward and Lothrop's Carlisle Building, which had been completed in 1887 a block to the south. As seen in the picture above (from the September 1, 1907, edition of The Washington Herald), the building originally topped out at five floors, with two grand, arched entrances positioned squarely in the middle of the facades on 11th and G Streets. Beginning with an additional floor and new roof in 1910, the building was expanded not only upwards but also on its east end in 1911 and to the north in 1914. The result was a much larger edifice, but with its grand entrances no longer in the middle of each side, as seen in the circa 1914 photograph below. The building's resulting asymmetry would ultimately be used as one of several excuses to tear it down.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. In October 1893, the The Washington Post deemed the new Palais Royal building "magnificent" and described its layout in great detail:

Lisner increasingly devoted his later years to philanthropic causes, including Georgetown Hospital, Children's Hospital, and the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington. In 1909 he joined the Board of Trustees of the George Washington University, to which he gave money to build the Lisner Library (now Lisner Hall) and, in his will, the Lisner Auditorium.

Meanwhile, the Palais Royal continued to prosper as a part of the Kresge empire. Even as the Great Depression set in, the Palais Royal weathered the storm well. A large new warehouse was constructed in 1931 on 1st Street NE, near Union Station, which was called "Evidence of Our Belief in the Return of Prosperity" in the company's ads. In 1933, the store ran a promotion for Ford V-8 automobiles, with a contest whereby patrons were to guess how many times the wheel in a car on display had turned. Fifteen lucky winners were given Ford V-8s on Thanksgiving Day. The following year a slogan contest was held. Mrs. Marie Rector reportedly won first prize--a new Marion electric range--for her winning entry: "The Palais Royal sells the best: everything will stand the test," which must have sounded much more fetching in 1934 than it does today.

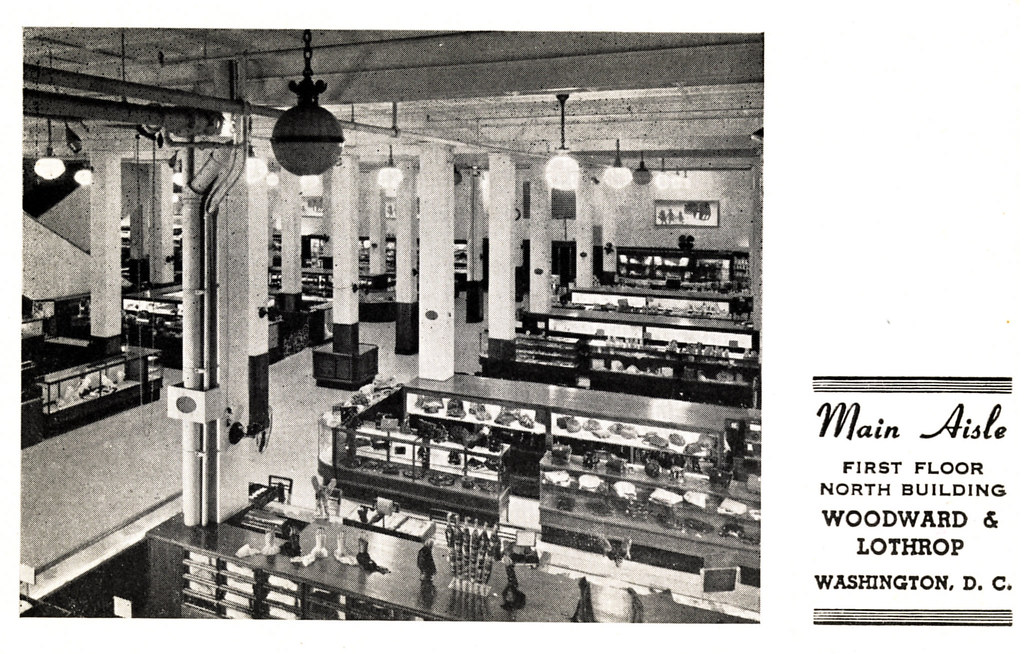

By 1943, the Palais Royal had three suburban branches, one in Bethesda and two in Arlington. But its days were numbered. Kresge sold the business to Woodward & Lothrop in 1946 for approximately $5.7 million, only slightly more than it had paid for it in 1924. Woodies began picking apart the assets it had acquired, closing or converting the branch stores. The main Palais Royal store became the Woodies North building, creating a truly sprawling retail complex that covered a block and half of downtown real estate. You could take an escalator down from the G Street side of the main Woodies Building and walk through an underground passageway across G Street to the Woodies North building. Woodies added the tunnel in 1951.When the Metro Center subway station was built in the early 1970s, it was designed so that its mezzanine connected directly to this passageway, providing ready access to either Woodies building.

By the early 1980s, Woodies was ready to downsize, and it sold off the North building for redevelopment. A large complex was then planned to fill the entire block, including a hotel on the north end to serve the Convention Center and a new office building where the Palais Royal building stood. Despite the fact that the Palais Royal had been designated as a D.C. "Category III" landmark in 1964 and again in 1973, the developer decided that saving it "would be a pain," as summed up by Mark Jenkins in the May 22, 1987, edition of City Paper.

Today a developer would be crazy to even think about completely demolishing a designated historic landmark like the Palais Royal, especially given that its facade could be incorporated into the planned office building. But at the time the D.C. Preservation League fought a losing, uphill battle to save it. Michael Quinn testified on behalf of the League before the DC Historic Preservation Officer in 1984. As summarized in the City Paper article, Quinn argued that the building represented a transition point between traditional masonry construction and the iron-skeleton approach of modern skyscrapers. Further, it's Chicago style had no other representative in Washington and thus was clearly significant. But it was no use; the League was outgunned. The director of the Office of Planning, the deputy mayor for economic development, the convention center general manager--all of them testified that it was necessary to tear down the old building. To mollify preservationists, the developer had agree to save the handsome but much smaller McLachlen Building (1910), designed by Jules Henri de Sibour and located on the southeast corner of the block. A consultant's report prepared at the time praised the McLachlen Building ("a particularly fine expression in Washington of the combination of Classical Revival and Chicago Style") while heaping scorn on the poor Palais ("does not have sufficient architectural merit today to warrant its preservation"). The report concluded that "the demolition of the Palais Royal is justified and necessary to permit the proposed Square 345 development which will provide important public benefits including the preservation and restoration of the highly significant and essentially unaltered McLachlen Building." The demolition was approved. After the Preservation League decided it was futile to appeal the decision, the old building came down in 1987. In 1989, the Washington Center office building was completed and opened on the Palais's old site.

Postscript: Thanks to Jerry McCoy and GWAlum for pointing out that the Washington Center's 11th Street entrance appears to incorporate two carved heads salvaged from the Palais Royal. The Palais had two sets of carved heads: a pair of male heads at the 11th Street entrance and a female pair (shown below) on the G Street side. One of each has been saved and placed above the 11th Street entrance to Washington Center; the other two are located over the entrance inside the lobby.

|

| The Shepherd Centennial Building with the Palais Royal store on the ground floor. (Author's collection). |

The firm began as a dry goods store specializing in "fancy" items, such as fans, gloves, jewelry, and handkerchiefs. It was founded by Abram Lisner (1855-1938), a short, wiry German immigrant who came to this country with his family at the age of 13. Plagued by epilepsy, Lisner was tutored privately as a child in New York and then went to work in his brother George's dry goods store on Broadway. It was with George's help that Abram expanded the business to Washington, opening up the Palais Royal and then buying out his brother's share in it two years later.

|

| (Source: The National Republican, Dec. 28, 1882.) |

Under Lisner's leadership the store proved very profitable. Lisner emphasized low prices and operated a cash-only business when most other dry goods stores offered credit. The reputation for quality merchandise at a low price built sales steadily, although Lisner was not immune to missteps. One dramatic incident occurred in March 1880 when Lisner accused his head clerk, Annie M. Nixon, of stealing a pair of kid gloves. Lisner seems to have confronted Miss Nixon in front of customers and had her arrested. Not a good idea, as it turned out. The Washington Post, not yet by any means a world-class newspaper, reported that the police officer at the local precinct station declared the whole affair a "put-up job" and let Nixon go with a "small collateral" for her appearance in police court the next day. The Post also said it had interviewed Lisner, who "told a voluminous story with evident delight" about how he had suspected Nixon of stealing items from the shop and had instructed another employee, Issac Teeney, to watch her. Teeney had subsequently found the purloined gloves in Nixon's coat pocket. The problem, however, was that Nixon was "a pretty brunette" and Teeney an African-American porter. The police court quickly absolved Nixon the next day. Teeney was presumed to be lying--heck, he probably stole the gloves himself. As soon as Judge Snell pronounced his verdict there was "prolonged applause, which the bailiffs could not control, and the young lady was immediately the recipient of congratulations." Lisner, in contrast, was "already unfavorably regarded by the general public," according to the Post, and was now reviled (at least for the moment) for making such a false accusation about the pretty brunette. The next day the Post ran a piece entitled "Lisner's Abject Terror," in which it described how Lisner had summoned the police to his store after having his life threatened by a man who had come in off the street. Lisner asked the officer who arrived to stay and protect him, but the policemen insisted he had to keep to his beat. "'But,' said Lisner, 'what if I am killed?' 'Well,' coolly retorted the officer, 'then I will find your body.'" -Such was the life of a Jewish shopkeeper in 1880 Washington.

That incident was probably soon forgotten, but Lisner continued to face difficulties due to his poor health. In 1884 he took a trip to the spas at Carlsbad in what is now the Czech Republic, but he did not think it did any good. He returned to New York City deeply discouraged, and his brother George induced him to stay there awhile. One afternoon, Abram borrowed $10 from his sister-in-law and went out to a buy some ice cream for her children. He also bought a handgun. The New York Times reported that, after regaling the children with the ice cream, he went upstairs and shot himself twice in the back of the head. Fortunately, the attempt was not successful; Lisner recovered and soon returned to Washington.

By 1887, Lisner was renting out more and more of the Centennial Building, employing some 250 clerks and steadily expanding his business. The Washington Post described the merchandise in his newly-opened Silk Department:

In evening silks and velvets are shown the richest effects. Plush and challie stripes, also raised freize and plush in tartan plaid effects on a tinted ground of plain crepe de chene or faille francaise are very beautiful. Moire francaise in light evening colors, shaded with a silver or gold filling attract attention. The new colors, such as mandarin, apple green, heliotrope and deep rose of moire antique have a rich appearance...

Soon Lisner decided it was time for new, larger quarters. A general trend had already been underway in the early 1890s for merchants to move from flood-prone Pennsylvania Avenue up to higher ground along the F Street corridor, which was becoming the new commercial center of Washington. Lisner followed the trend—and pushed it a little—by choosing the site on 11th and G Streets for his new building, a block north of the established commercial drag. Lisner was confident he would do well there, and he did.

The Palais Royal building, completed in 1893 at a cost of $250,000, was designed by Washington architect Harvey L. Page in the Chicago style, a practical design vocabulary for high-rise commercial buildings that stressed large windows and restrained neoclassical trim. The building was similar to Woodward and Lothrop's Carlisle Building, which had been completed in 1887 a block to the south. As seen in the picture above (from the September 1, 1907, edition of The Washington Herald), the building originally topped out at five floors, with two grand, arched entrances positioned squarely in the middle of the facades on 11th and G Streets. Beginning with an additional floor and new roof in 1910, the building was expanded not only upwards but also on its east end in 1911 and to the north in 1914. The result was a much larger edifice, but with its grand entrances no longer in the middle of each side, as seen in the circa 1914 photograph below. The building's resulting asymmetry would ultimately be used as one of several excuses to tear it down.

The general effect of the building is that of solidity, something after the nature of the older Government buildings, but its high Romanesque arches and arcaded windows combine to give it a grace not possessed by those severely classic structures.

The next feature to strike the beholder is the great number of windows, which occupy fully one-half the front space of the building, making it almost transparent from without, and flooding the interior with the natural light of day. The immense show windows on the first floor are the largest in the city, and their effect is fine.

The interior of the building is finished in hard woods, contrasting very prettily with the cream tints of the walls... In the basement is the engine-room and dynamos, by which the building will be brilliantly lighted by day and night. The cash room, in which centers the pneumatic-tube system, bringing money from all parts of the building and whisking the change back again in a minute, is also in the basement.

The first floor will be devoted to notions and small wares such as are wanted by the casual customer...

The entire second floor will be filled with millinery and dress goods... Here the ladies will find ample room for examining and matching goods, free from the bustle and confusion of the first floor.

Furs, cloaks, and costumes will fill the space on the third floor not occupied by the offices and the clerks' lunch room, while on the fourth floor will be found the upholstery, art embroidery, stamping, pictures and picture framing, toys, and games departments, all complete and up to date.

Two features of the mezzanine story are the ladies' reception-room, fitted up in Oriental style and supplied with magazines, stationary, and all the appurtenances of a woman's club. The manicure department and the mirror-lined dark room for the matching of gowns for evening wear are also unique and popular ideas....Despite warnings from some quarters that putting the store a block away from F Street would be a bad idea, the store prospered at its new location, benefiting from streetcar lines that ran right past it. By the time of its third expansion in 1914, over 600 employees, mostly clerks, worked there. However, by 1924, Lisner was finally ready to retire from the mercantile business. That year he sold his business to the S.S. Kresge Department Stores Corporation for approximately $5 million.

|

| Lingerie department c. 1921 (Source: Library of Congress) |

Lisner increasingly devoted his later years to philanthropic causes, including Georgetown Hospital, Children's Hospital, and the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington. In 1909 he joined the Board of Trustees of the George Washington University, to which he gave money to build the Lisner Library (now Lisner Hall) and, in his will, the Lisner Auditorium.

|

| (Source: D.C. Preservation League archives) |

Meanwhile, the Palais Royal continued to prosper as a part of the Kresge empire. Even as the Great Depression set in, the Palais Royal weathered the storm well. A large new warehouse was constructed in 1931 on 1st Street NE, near Union Station, which was called "Evidence of Our Belief in the Return of Prosperity" in the company's ads. In 1933, the store ran a promotion for Ford V-8 automobiles, with a contest whereby patrons were to guess how many times the wheel in a car on display had turned. Fifteen lucky winners were given Ford V-8s on Thanksgiving Day. The following year a slogan contest was held. Mrs. Marie Rector reportedly won first prize--a new Marion electric range--for her winning entry: "The Palais Royal sells the best: everything will stand the test," which must have sounded much more fetching in 1934 than it does today.

|

| This view, facing east on G Street, shows the brown Palais Royal building just past the intersection on the left and the cream-colored Woodies building opposite on the right. |

By 1943, the Palais Royal had three suburban branches, one in Bethesda and two in Arlington. But its days were numbered. Kresge sold the business to Woodward & Lothrop in 1946 for approximately $5.7 million, only slightly more than it had paid for it in 1924. Woodies began picking apart the assets it had acquired, closing or converting the branch stores. The main Palais Royal store became the Woodies North building, creating a truly sprawling retail complex that covered a block and half of downtown real estate. You could take an escalator down from the G Street side of the main Woodies Building and walk through an underground passageway across G Street to the Woodies North building. Woodies added the tunnel in 1951.When the Metro Center subway station was built in the early 1970s, it was designed so that its mezzanine connected directly to this passageway, providing ready access to either Woodies building.

By the early 1980s, Woodies was ready to downsize, and it sold off the North building for redevelopment. A large complex was then planned to fill the entire block, including a hotel on the north end to serve the Convention Center and a new office building where the Palais Royal building stood. Despite the fact that the Palais Royal had been designated as a D.C. "Category III" landmark in 1964 and again in 1973, the developer decided that saving it "would be a pain," as summed up by Mark Jenkins in the May 22, 1987, edition of City Paper.

Today a developer would be crazy to even think about completely demolishing a designated historic landmark like the Palais Royal, especially given that its facade could be incorporated into the planned office building. But at the time the D.C. Preservation League fought a losing, uphill battle to save it. Michael Quinn testified on behalf of the League before the DC Historic Preservation Officer in 1984. As summarized in the City Paper article, Quinn argued that the building represented a transition point between traditional masonry construction and the iron-skeleton approach of modern skyscrapers. Further, it's Chicago style had no other representative in Washington and thus was clearly significant. But it was no use; the League was outgunned. The director of the Office of Planning, the deputy mayor for economic development, the convention center general manager--all of them testified that it was necessary to tear down the old building. To mollify preservationists, the developer had agree to save the handsome but much smaller McLachlen Building (1910), designed by Jules Henri de Sibour and located on the southeast corner of the block. A consultant's report prepared at the time praised the McLachlen Building ("a particularly fine expression in Washington of the combination of Classical Revival and Chicago Style") while heaping scorn on the poor Palais ("does not have sufficient architectural merit today to warrant its preservation"). The report concluded that "the demolition of the Palais Royal is justified and necessary to permit the proposed Square 345 development which will provide important public benefits including the preservation and restoration of the highly significant and essentially unaltered McLachlen Building." The demolition was approved. After the Preservation League decided it was futile to appeal the decision, the old building came down in 1987. In 1989, the Washington Center office building was completed and opened on the Palais's old site.

Postscript: Thanks to Jerry McCoy and GWAlum for pointing out that the Washington Center's 11th Street entrance appears to incorporate two carved heads salvaged from the Palais Royal. The Palais had two sets of carved heads: a pair of male heads at the 11th Street entrance and a female pair (shown below) on the G Street side. One of each has been saved and placed above the 11th Street entrance to Washington Center; the other two are located over the entrance inside the lobby.

you're killing me with these old buildings!

ReplyDeletefantastic write-up. wish so much that we could go back in time and save some of these!

How little did I know of the history of Woodie's old North Building. Palais Royal, indeed. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteKeep up the amazing work--this is a great blog!

ReplyDelete--Quondam Washington

The Chicago School is one of those fungable names that tends to be used the way Colonial does today with row houses. Harvey L. Page was probably the most innovative interpreter of the Richardsonian Romanesque style, of which this building is a fine example of. Him, Hornblower and Marshall, Schneider, and more rank DC as one of the finest in Richardsonian Romanesque development.

ReplyDeleteNow, I wonder on whose wall, desk, or shelf the other pair of carved heads reside!

ReplyDeleteIt turns out the other pair are located above the entrance inside the lobby of the Washington Center building.

DeleteMy mother worked at the Palais Royal during the Depression. Thanks for the history. Interesting to learn where Lisner Auditorium got its name too.

ReplyDeleteAnyone know what happened to Velatti’s (sp) Candy Store, near Woodies North?

ReplyDeleteSeen now on Georgia Avenue in center of Silver Spring.

ReplyDelete