Sweatshop: The Bureau of Engraving and Printing c. 1905

With the exception of the reviled “continentals” circulated during the American Revolution, it wasn’t until the Civil War—when the government essentially needed to write IOU’s for hard currency it didn’t have—that the production of paper money by the federal government began in earnest in this country. In the early years, this was done in the main Treasury building next to the White House, but officials soon realized that the industrial aspects of printing large quantities of paper money dictated the need for a separate facility. Congress finally authorized $300,000 for such a facility in 1878, and after a prominent piece of real estate at 14th and B Streets (now 14th and Independence Avenue NW) was purchased from banker William W. Corcoran, construction commenced.

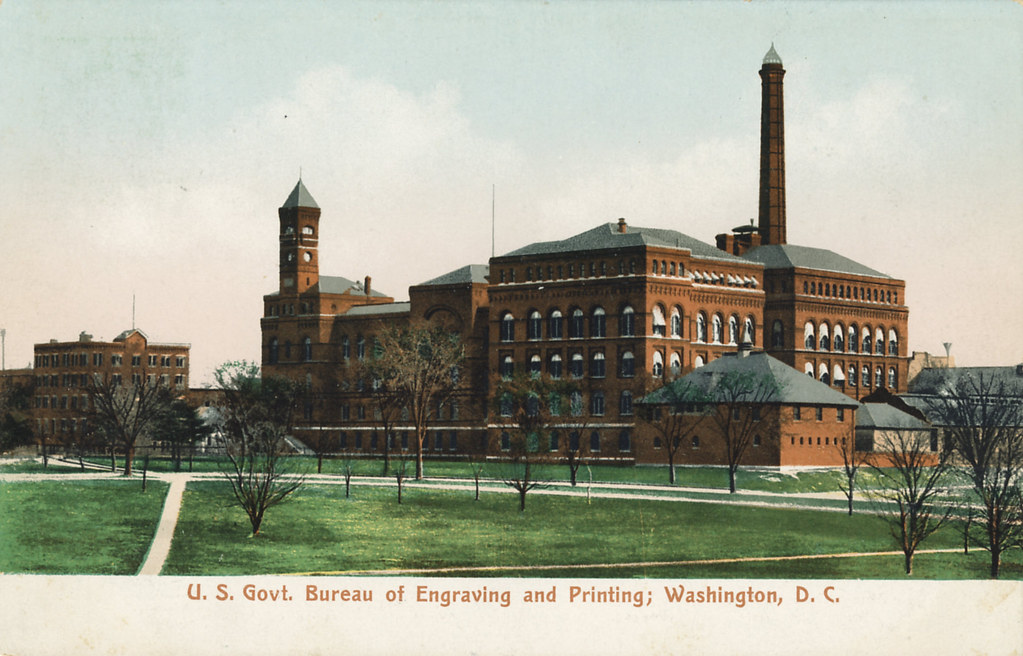

The building to house the Treasury's Bureau of Engraving and Printing, opened in 1880, was designed by James G. Hill, who would go on to hit his stride with several classic Richardson Romanesque buildings, including the Washington Loan and Trust Company building previously discussed. This one is a bit of a transitional piece, still adhering to techniques that were soon to be out of fashion, including the use of pressed red brick and architectural elements of the Italianate style popular in the mid-19th century. There are also many features of the Queen Anne style here. But there are also Romanesque elements, pointing the way to a coming trend.

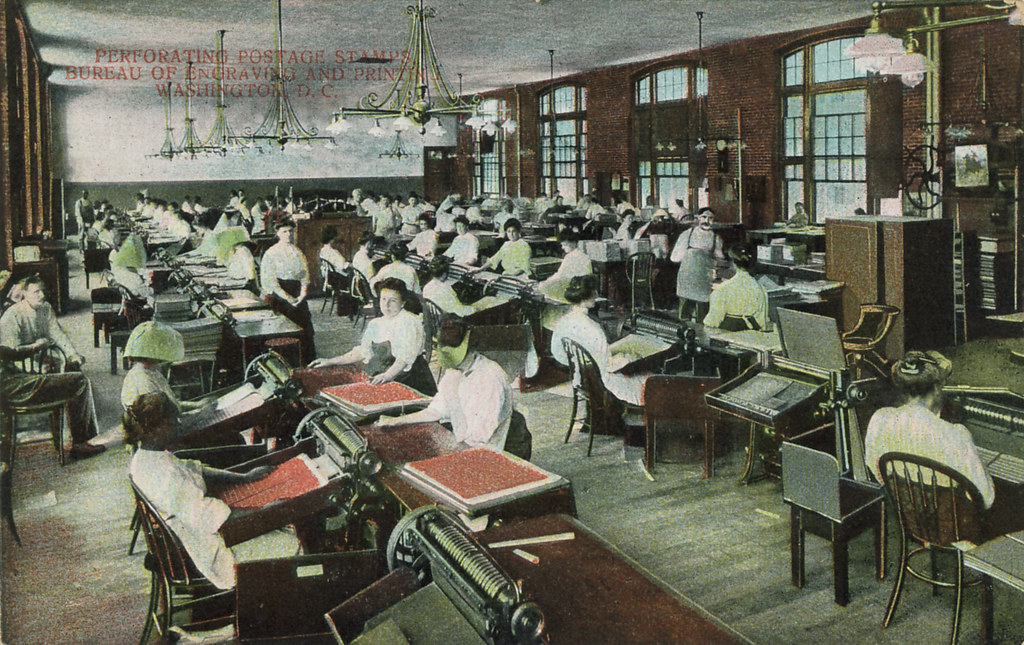

Printing of over-sized national bank notes, four to a page, was a major activity of the Bureau in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and it was done almost entirely on small hand presses, which were favored (and still are, among aficionados of hand-crafted printing) for their high-quality results. Rows upon rows of such machines were lined up in the big workrooms of the Bureau’s main building. The machines, nicknamed "spider presses," had long spoke-like levers on one side to give the printers plenty of leverage when pressing individual sheets of paper against plates inked with a banknote's design. It took two people to operate one of these machines efficiently: a printer and an assistant, or press-feeder. The printer first heated an engraved metal plate on a small stove and then vigorously rolled ink on to it, forcing the ink into the fines lines of the engravings. Next, the excess ink had to be removed from the smooth surface of the plate by a brisk rubbing with a piece of starched muslin, followed by "polishing" the plate, which the printer did with palms of his hands, removing every trace of ink from the smooth surface without disturbing any of the ink sitting in the grooves of the engraving. The printer then moved the plate to the press itself, and his assistant laid a dampened sheet of paper on it. The printer forced the plate through the rollers of the press by turning the spider levers, and his assistant then removed the printed sheet and set it aside to dry. This printed one side of a sheet; the sheet then had to be rewet and run through again to print the other side.

These postcard views of the main press room give some sense of the working conditions for this messy, back-breaking enterprise. Row upon row of hand presses can be seen lining the main press room, with just a series of small wooden paddles arranged along the ceiling to provide rudimentary air circulation as they turned. Just the toxic side effects alone of directly handling all of that ink must have constituted a substantial health risk. In 1904, the Washington Post reported that "ink from the bureau pollutes the Potomac, and probably is responsible for the death of many fish." By that time a separate laundry building had been constructed behind the main bureau building, its sole function being to clean all the muslin rags used to wipe the printing plates. Bureau officials proposed constructing a special catch basin for the runoff from the laundry to keep it from polluting the river.

The building quickly became overcrowded and unsafe, despite its seemingly capacious size. An assortment of additions and small outbuildings, such as the laundry building, were added to the Bureau's complex, but it never seemed to be enough to satisfy the need. In his annual report for 1898, the Bureau's director complained that "there has been no addition to the building since 1896.... The condition of this building, crowded as it is with operatives, is not in accordance with good business methods or proper sanitation. It is with great concern that I call attention to the immense amounts of combustible material stored therein, which make the possibilities of fire so great as to be alarming... This material includes millinets, oils, turpentine, benzine, colors, chemicals, blanketing, paper, &c." Furthermore, "Every available foot of space in the bureau for hand plate-printing presses is now occupied, and still we are unable in the regular hours to keep up with the average number of sheets to be produced daily." Frequently the bureau resorted to round-the-clock operations to get production up, but that seemed to only add to the stress, wear and tear, and other operational problems. Young women who finished their shifts in the middle of the night were left to walk home at dangerous hours from a part of town that was not very safe, especially at night.

The printers were all men, naturally, but the press-feeders were women. Why is that? It seems no self-respecting man would take the job of press-feeder because it paid so little, only $1.25 per day in 1880s and 1890s. Of course, you could theoretically get boys to do the job, since there weren't any child-labor laws before 1890, but, according to the Washington Post, the printers objected that children didn't have the proper skill and dexterity to feed paper just the right way into the finicky presses. The result was back-breaking work for young women who endured deplorable conditions and earned little pay. A passionate letter to the Post in 1882 described "all that is left of what used to be the forms of thirty women.... Fate and necessity combined, forced them at an early age into the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. You see the result of stifling air and overheated rooms, standing on their feet for continuous hours, whilst performing the most incessant labor... These women have given all the days of their youth and early womanhood to the service of the Government, and now, when they should be in the prime of their strength and usefulness, they are almost wrecked...."

By 1909, the women were organizing themselves into a union, and a committee of them formally petitioned that their pay be raised from $1.50 to $2 per day. The director of the bureau said he was "in entire sympathy with any movement to lighten the burdens of the women workers in this bureau" but quickly noted that "As to increased pay, that is a matter which must be settled by Congress" and furthermore, "When both sides of this salary question are looked into, it is plain that the women workers in the bureau are well off." The new press-feeders' union would clearly have its work cut out for it.

The building to house the Treasury's Bureau of Engraving and Printing, opened in 1880, was designed by James G. Hill, who would go on to hit his stride with several classic Richardson Romanesque buildings, including the Washington Loan and Trust Company building previously discussed. This one is a bit of a transitional piece, still adhering to techniques that were soon to be out of fashion, including the use of pressed red brick and architectural elements of the Italianate style popular in the mid-19th century. There are also many features of the Queen Anne style here. But there are also Romanesque elements, pointing the way to a coming trend.

Printing of over-sized national bank notes, four to a page, was a major activity of the Bureau in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and it was done almost entirely on small hand presses, which were favored (and still are, among aficionados of hand-crafted printing) for their high-quality results. Rows upon rows of such machines were lined up in the big workrooms of the Bureau’s main building. The machines, nicknamed "spider presses," had long spoke-like levers on one side to give the printers plenty of leverage when pressing individual sheets of paper against plates inked with a banknote's design. It took two people to operate one of these machines efficiently: a printer and an assistant, or press-feeder. The printer first heated an engraved metal plate on a small stove and then vigorously rolled ink on to it, forcing the ink into the fines lines of the engravings. Next, the excess ink had to be removed from the smooth surface of the plate by a brisk rubbing with a piece of starched muslin, followed by "polishing" the plate, which the printer did with palms of his hands, removing every trace of ink from the smooth surface without disturbing any of the ink sitting in the grooves of the engraving. The printer then moved the plate to the press itself, and his assistant laid a dampened sheet of paper on it. The printer forced the plate through the rollers of the press by turning the spider levers, and his assistant then removed the printed sheet and set it aside to dry. This printed one side of a sheet; the sheet then had to be rewet and run through again to print the other side.

These postcard views of the main press room give some sense of the working conditions for this messy, back-breaking enterprise. Row upon row of hand presses can be seen lining the main press room, with just a series of small wooden paddles arranged along the ceiling to provide rudimentary air circulation as they turned. Just the toxic side effects alone of directly handling all of that ink must have constituted a substantial health risk. In 1904, the Washington Post reported that "ink from the bureau pollutes the Potomac, and probably is responsible for the death of many fish." By that time a separate laundry building had been constructed behind the main bureau building, its sole function being to clean all the muslin rags used to wipe the printing plates. Bureau officials proposed constructing a special catch basin for the runoff from the laundry to keep it from polluting the river.

The building quickly became overcrowded and unsafe, despite its seemingly capacious size. An assortment of additions and small outbuildings, such as the laundry building, were added to the Bureau's complex, but it never seemed to be enough to satisfy the need. In his annual report for 1898, the Bureau's director complained that "there has been no addition to the building since 1896.... The condition of this building, crowded as it is with operatives, is not in accordance with good business methods or proper sanitation. It is with great concern that I call attention to the immense amounts of combustible material stored therein, which make the possibilities of fire so great as to be alarming... This material includes millinets, oils, turpentine, benzine, colors, chemicals, blanketing, paper, &c." Furthermore, "Every available foot of space in the bureau for hand plate-printing presses is now occupied, and still we are unable in the regular hours to keep up with the average number of sheets to be produced daily." Frequently the bureau resorted to round-the-clock operations to get production up, but that seemed to only add to the stress, wear and tear, and other operational problems. Young women who finished their shifts in the middle of the night were left to walk home at dangerous hours from a part of town that was not very safe, especially at night.

The printers were all men, naturally, but the press-feeders were women. Why is that? It seems no self-respecting man would take the job of press-feeder because it paid so little, only $1.25 per day in 1880s and 1890s. Of course, you could theoretically get boys to do the job, since there weren't any child-labor laws before 1890, but, according to the Washington Post, the printers objected that children didn't have the proper skill and dexterity to feed paper just the right way into the finicky presses. The result was back-breaking work for young women who endured deplorable conditions and earned little pay. A passionate letter to the Post in 1882 described "all that is left of what used to be the forms of thirty women.... Fate and necessity combined, forced them at an early age into the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. You see the result of stifling air and overheated rooms, standing on their feet for continuous hours, whilst performing the most incessant labor... These women have given all the days of their youth and early womanhood to the service of the Government, and now, when they should be in the prime of their strength and usefulness, they are almost wrecked...."

By 1909, the women were organizing themselves into a union, and a committee of them formally petitioned that their pay be raised from $1.50 to $2 per day. The director of the bureau said he was "in entire sympathy with any movement to lighten the burdens of the women workers in this bureau" but quickly noted that "As to increased pay, that is a matter which must be settled by Congress" and furthermore, "When both sides of this salary question are looked into, it is plain that the women workers in the bureau are well off." The new press-feeders' union would clearly have its work cut out for it.

|

| By 1904, women were also employed inspecting newly-made currency, as seen here. |

One has to wonder why a more automated printing system hadn't been introduced by the early 1900s, when these postcards were made. Sophisticated steam-powered industrial machinery was certainly common by then. This is where politics comes into the mix. Steam-powered presses were certainly available as early as the 1870s, before the Bureau had even moved to its own building. But switching to steam power would mean elimination of lots of jobs, and that was a problem. Those seeking to protect the jobs of the printers also had the excuse that steam presses at first did not produce the same quality results as hand presses, giving rise to fears that forgers could more easily duplicate the currency produced by such presses. The supporters of hand presses dominated Congress, which repeatedly passed laws severely restricting the use of steam presses at the bureau. It wasn't until 1912 that legislation finally passed allowing power presses to be gradually phased in over a five-year period.

In the midst of that conversion, the bureau finally gave up on its 1880 building altogether, moving in 1914 to a much larger new limestone neoclassical building just to the south of the original complex. That building remains the bureau's main plant to this day, although it has been supplemented by an annex built on the other side of 14th Street in 1938 and connected to the main building by two underground tunnels. The 1880 building was turned over to the government for other agencies to use and has been occupied primarily by Agriculture Department office workers. Various small-scale outbuildings, such as the old laundry building, had been built to supplement the 1880 building and occupied the space between it and the 1914 building. These remained in place for many years but were finally cleared away to make room for the U.S. Holocaust Museum, which opened in 1993.

In the midst of that conversion, the bureau finally gave up on its 1880 building altogether, moving in 1914 to a much larger new limestone neoclassical building just to the south of the original complex. That building remains the bureau's main plant to this day, although it has been supplemented by an annex built on the other side of 14th Street in 1938 and connected to the main building by two underground tunnels. The 1880 building was turned over to the government for other agencies to use and has been occupied primarily by Agriculture Department office workers. Various small-scale outbuildings, such as the old laundry building, had been built to supplement the 1880 building and occupied the space between it and the 1914 building. These remained in place for many years but were finally cleared away to make room for the U.S. Holocaust Museum, which opened in 1993.

|

| The original bureau buildings are barely visible behind the new building in this view. |

The only outbuilding to survive, known as Annex #3, was designed by James Knox Taylor and built along the western side of the 1880 building in 1905. The following two postcard views show the 1880 building before and after this annex was built next to it. The third and fourth views are of women making postage stamps in the annex. The building now houses a cafeteria and offices for the Holocaust Museum.

DEAD ON DESCRIPTION OF THE ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AT PLAY AND IT'S PLACE IN HISTORY. A PLEASURE TO READ INFORMED HISTORICAL ANALYSIS.

ReplyDeletelOVE THE OPERABLE TRANSOM WINDOWS.

Wonderful write-up and great images. I was wondering if you know anything about the bureau's black workers. The Scurlocks took a series of photos of bureau workers in 1951. Most, but not all, were black women. Any idea when/ why the worker demographic shifted? Thanks!

ReplyDeletesee: http://sirismm.si.edu/archivcenter/scurlock/618ns0227887-01jp.jpg

http://sirismm.si.edu/archivcenter/scurlock/AC0618.004.0001066.jpg

Great question about the demographics. Unfortunately I do not have any information specific to the Bureau about that. Maybe one of our readers knows more...

ReplyDelete