Mr. Mullett's Bank Building: 150 Years on Pennsylvania Avenue

The intersection of 7th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., used to be the heart of Washington's commercial district, and the Central National Bank Building has presided over the comings and goings there for well over a century. The building dates to circa 1860, when it was built as a five-story Renaissance Revival hotel, one of the largest in the city at the time and the second in that block, after Brown's Marble Hotel. The hotel was originally called Seaton House and then renamed the St. Marc in 1871. In 1887 the Central National Bank bought the building for $105,000 and commissioned architect Alfred B. Mullett to renovate it for banking purposes. The bank's officers clearly wanted a distinctive new look that would appropriately call attention to their institution. Mullett, perhaps Washington's most prominent architect at the time, responded with a striking new brownstone façade and the two distinctive towers that continue to draw attention to the building to this day.

Mullett (1834-1890) was an interesting and rather controversial figure. His architectural training seemed inauspicious. He started as an apprentice in the Cincinnati, Ohio, office of architect Isaiah Rogers and, after serving in the Union Army, came to Washington to work under Rogers in the office of the supervising architect of the Treasury Department. After Rogers left in 1865, Mullett got himself promoted as supervising architect, an enormously powerful position that essentially gave him primary control over all major federal building projects that were to occur in the post-war years. While practicing several styles, he clearly favored the grand, Second Empire vocabulary and is perhaps best known for his State, War, and Navy Building (now called the Eisenhower Executive Office Building) next to the White House, one of the most exuberant Victorian gingerbread confections to be found anywhere in the country, a building so ornately decorated you have to admire its sheer, unbridled extravagance. Mullett also designed a number of other large, ornate public buildings in cities throughout the United States.

Inevitably objections arose about the expense of all these structures. Mullett was accused of unnecessary extravagance, and at one point his mental stability was questioned, leading him to resign as supervising architect in December 1874. Despite his considerable architectural talents, Mullett seems to have struggled with people continually and was a popular political target. The New York Sun reportedly called him "the most arrogant, pretentious, and preposterous little humbug in the United States." Despite these problems, Mullett took up private practice as an architect in Washington after leaving the government, designing approximately 40 buildings during a booming period of the city's growth, of which only a handful are still around. One of them is the Central National Bank Building.

Mullett lived in a mansion on the northwest corner of 25th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW in the West End. One of his ventures in 1889 was the construction of three rowhouses (which are still standing) at the other end of the same block, which he hoped would provide income for his wife, Pearl Pacific Myrick Mullett. However, by 1890 Mullett was in financial straits, partly because he couldn't sell these speculative investment houses and partly because he had lost a court claim for his fees for designing the State, War, and Navy Building. Furthermore, health problems were plaguing both his wife and himself. One day in October 1890, Mullett came home from work at 3:30 in the afternoon feeling "brighter and in better health than [he had] in many days," according to the account in the Washington Post, but later that afternoon his attitude changed:

"He at this time complained of being tired and drowsy, and said to Mrs. Mullett that he would retire for a nap. Mrs. Mullett and their eldest daughter, Miss Josie, accompanied him upstairs to his room. He expressed his desire for a little beef tea, and Mrs. Mullett went downstairs to prepare it for him, the daughter remaining in an adjacent apartment.

"Almost before Mrs. Mullett reached the lower floor a sharp shot rang out in the bedchamber, startling the entire household. Hastily going to the chamber door they saw Mr. Mullett lying on the floor gasping for breath and the blood oozing from a wound in his forehead...."

Despite his own life being tragically cut short, some of Mullett's great architectural achievements have lived on for more than a century. The Central National Bank, however, remained in its Mullett-designed building only until 1907, when it merged with the National Bank of Washington, which consolidated all of its operations in its own adjacent Romanesque Revival building (seen below), constructed in 1889.

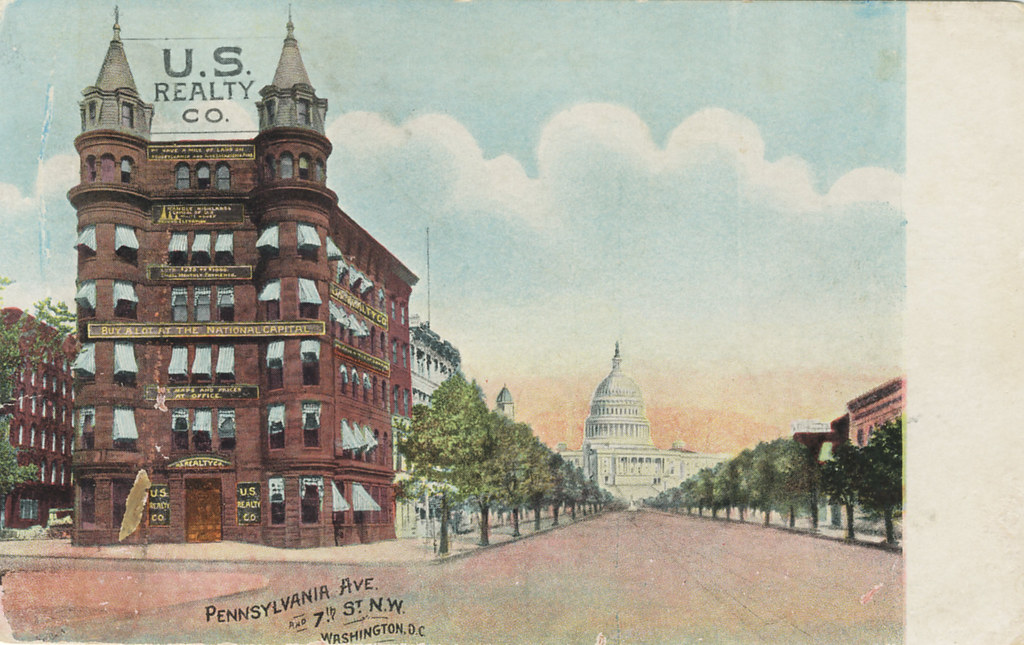

The Mullett building was then leased to a variety grocers, drugstores, lunch rooms, and at least one real estate business. A large metal frame for lighted electric signs was erected between the two turrets, as seen in this postcard view.

Another night-time view from 1918, seen here, shows the sign lit up with a patriotic war message that seems to be competing with a similar electric sign atop the nearby Central Union Mission building.

The building was sold in the 1940s, and the Apex Liquor Store began a large and thriving business that lasted on this site until 1983. In those days, many people knew the building as the Apex Building because of the liquor store there, which also gave knowing Washingtonians a good chuckle, since the Temperance Fountain, erected in 1882, was (and still is) situated just in the plaza outside its front entrance.

Mullett (1834-1890) was an interesting and rather controversial figure. His architectural training seemed inauspicious. He started as an apprentice in the Cincinnati, Ohio, office of architect Isaiah Rogers and, after serving in the Union Army, came to Washington to work under Rogers in the office of the supervising architect of the Treasury Department. After Rogers left in 1865, Mullett got himself promoted as supervising architect, an enormously powerful position that essentially gave him primary control over all major federal building projects that were to occur in the post-war years. While practicing several styles, he clearly favored the grand, Second Empire vocabulary and is perhaps best known for his State, War, and Navy Building (now called the Eisenhower Executive Office Building) next to the White House, one of the most exuberant Victorian gingerbread confections to be found anywhere in the country, a building so ornately decorated you have to admire its sheer, unbridled extravagance. Mullett also designed a number of other large, ornate public buildings in cities throughout the United States.

Inevitably objections arose about the expense of all these structures. Mullett was accused of unnecessary extravagance, and at one point his mental stability was questioned, leading him to resign as supervising architect in December 1874. Despite his considerable architectural talents, Mullett seems to have struggled with people continually and was a popular political target. The New York Sun reportedly called him "the most arrogant, pretentious, and preposterous little humbug in the United States." Despite these problems, Mullett took up private practice as an architect in Washington after leaving the government, designing approximately 40 buildings during a booming period of the city's growth, of which only a handful are still around. One of them is the Central National Bank Building.

Mullett lived in a mansion on the northwest corner of 25th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW in the West End. One of his ventures in 1889 was the construction of three rowhouses (which are still standing) at the other end of the same block, which he hoped would provide income for his wife, Pearl Pacific Myrick Mullett. However, by 1890 Mullett was in financial straits, partly because he couldn't sell these speculative investment houses and partly because he had lost a court claim for his fees for designing the State, War, and Navy Building. Furthermore, health problems were plaguing both his wife and himself. One day in October 1890, Mullett came home from work at 3:30 in the afternoon feeling "brighter and in better health than [he had] in many days," according to the account in the Washington Post, but later that afternoon his attitude changed:

"He at this time complained of being tired and drowsy, and said to Mrs. Mullett that he would retire for a nap. Mrs. Mullett and their eldest daughter, Miss Josie, accompanied him upstairs to his room. He expressed his desire for a little beef tea, and Mrs. Mullett went downstairs to prepare it for him, the daughter remaining in an adjacent apartment.

"Almost before Mrs. Mullett reached the lower floor a sharp shot rang out in the bedchamber, startling the entire household. Hastily going to the chamber door they saw Mr. Mullett lying on the floor gasping for breath and the blood oozing from a wound in his forehead...."

Despite his own life being tragically cut short, some of Mullett's great architectural achievements have lived on for more than a century. The Central National Bank, however, remained in its Mullett-designed building only until 1907, when it merged with the National Bank of Washington, which consolidated all of its operations in its own adjacent Romanesque Revival building (seen below), constructed in 1889.

The Mullett building was then leased to a variety grocers, drugstores, lunch rooms, and at least one real estate business. A large metal frame for lighted electric signs was erected between the two turrets, as seen in this postcard view.

Another night-time view from 1918, seen here, shows the sign lit up with a patriotic war message that seems to be competing with a similar electric sign atop the nearby Central Union Mission building.

The building was sold in the 1940s, and the Apex Liquor Store began a large and thriving business that lasted on this site until 1983. In those days, many people knew the building as the Apex Building because of the liquor store there, which also gave knowing Washingtonians a good chuckle, since the Temperance Fountain, erected in 1882, was (and still is) situated just in the plaza outside its front entrance.

|

| A sun-washed view of the building from a summer afternoon in 1980 (photo by the author). |

After weathering the long decline of downtown Washington, the Apex Building was renovated in 1984 by Sears, Roebuck, and Co., as headquarters for its Sears World Trade arm. Sears added a story on top of the building but otherwise generally restored the exterior to its original appearance, with the exception that they decided to paint the brownstone an odd mocha color that it still retains today. Sears stayed in the building for less than a decade, and now it is the headquarters of the National Council of Negro Women, Inc.

|

| The building as it looks today (photo by the author). |

shame that all of that nice commercial frontage on pennsylvania avenue isn't used for shops.

ReplyDeletegreat blog

ReplyDeleteI worked at the National Bank of Washington in 1959 and 1960. I'll never forget the great times, the great people and how much I learned as a young girl from Chicago, IL Probably one of the best times of my life.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the information. Sometimes it is better to get to the point of things. I don't like historical information that gets in its own way. The pictures really help too!. this information will allow me to do a little bio on my own with other resources. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteNote in the second picture that present-day Indiana Avenue was called Louisiana Avenue. Once upon a time, Louisiana ran to the southwest from D to C, and Indiana ran southeast from D to C. There's still a tiny bit of the southeastern end of Indiana Avenue that comes into the intersection of 1st and C.

ReplyDeleteIn the third picture, they appear to have mistaken 7th St. for 9th St. Far more interesting, though, they've given the U.S. Capitol a gilded dome.