Terracotta Triumph: The Westory Building

The view here is of the intersection of 14th and F Streets, N.W., facing east, around 1910-1915. The dark building glimpsed on the near right (southwest) corner is the Willard Hotel. Behind it, on the southeast corner, is the Ebbitt House, discussed in a previous post. On the left side, the prominent building on the northeast corner is the recently completed Westory Building, today's subject...

The first decade of the 20th century saw a tremendous explosion of commercial real estate development in downtown Washington, and much of it was concentrated in the newly christened "financial" district along 14th and 15th Streets NW near the Treasury Building. Each new building, naturally, strove for attention through one form of superlative design or another. The Westory, completed in 1907, is an interesting case in point.

![]()

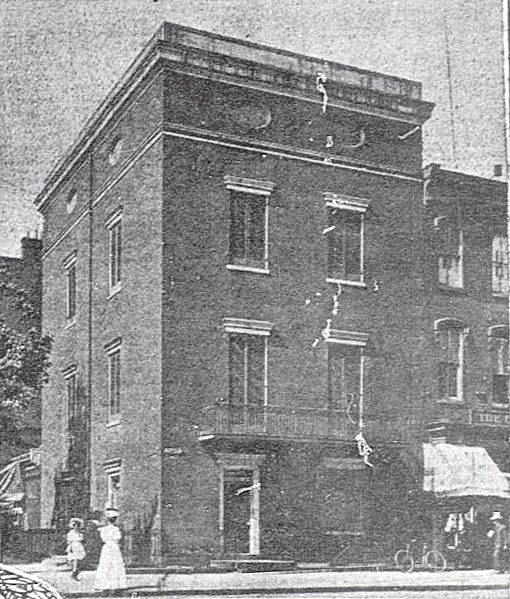

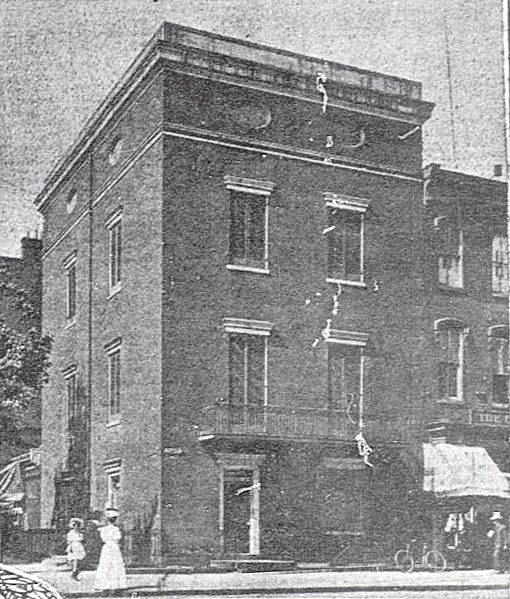

Before the Westory, the mansion of Dr. Robert King Stone stood on this site, as seen in the photograph above from the May 27, 1906, edition of the Washington Times. Stone's mansion was typical of the many stately brick residences that lined the streets of this neighborhood through most of the 19th century until larger commercial buildings gradually began to encroach in the 1870s. The Greek Revival house with its distinctive oval windows in the attic was built circa 1849 for Dr. Stone as a wedding gift from his wealthy father. Stone became perhaps the most prominent physician in Washington by the time he died in 1872. He had been President Lincoln's personal physician, and was summoned from his home here on the night of April 14, 1865, to attend to the mortally-wounded president at nearby Ford's Theater. After Dr. Stone's death, his widow remained in the house, refusing all offers to buy it and ignoring the rapid commercial changes that were engulfing the neighborhood around her. After her death in 1905, the property was finally sold, for an astonishing $76 per square foot, to developer George Higbee, who then immediately tore down the house and built the Westory in its place. In addition to the $190,000 he spent on the lot, Higbee probably put about $200,000 into constructing and decorating the new office building--a substantial investment at the time.

As the nine-story "skyscraper" neared completion in the summer of 1907, the Washington Post, with perhaps a slight bit of exaggeration, called it the "Flatiron's Rival," because it had been built on a narrow lot, as the famous New York landmark had been. The building, designed by Henry Jeckel of Boston, features elaborate white-glazed terracotta ornamentation (a new technique at the time), including a row of scowling lions atop the seventh floor and a massive cornice with ornamental wreaths and fleurs-de-lis that is probably too high for people to appreciate. At street-level are a series of massive two-story Ionic columns striped with distinctive rusticated bands. The lobby was originally finished in marble, mosaic, and bronze, with an elaborate stairway leading up to an equally lavish mezzanine level. Plate-glass windows, another very modern touch, allowed passersby to appreciate the interior decoration.

Commenting on the new building in November 1907, the Washington Times noted approvingly that the replacement of the old red-brick mansion of Dr. Stone with this tall, ornate, and thoroughly modern structure was a major step up for the neighborhood and that the new edifice beautifully complemented the Willard Hotel diagonally opposite. "The effect of this building upon values of realty in the neighborhood cannot be questioned," the Times proclaimed. The boom was on, and no end was in sight.

Of course, the building and its neighborhood have had theirs ups and downs since those heady days. The decline of downtown Washington in the 1960s and 1970s put old buildings such as the Westory in serious danger of demolition. In 1981, Don't Tear it Down, the historic preservation group that would later become the D.C Preservation League, surveyed downtown for buildings that did not have historic landmark protection but that deserved it--the Westory was on the list. While the building appears not to have officially gained historic status, developers got the message and made sure it was preserved.

![]()

An expansion of the building was designed by Shalom Baranes Associates and completed in 1990, winning an award for excellence by the American Institute of Architects in 1992. A second phase of the expansion was added in 2002. Benjamin Forgey, longtime architecture critic for the Evening Star and later the Washington Post, commented in 1993 on the building's addition: "The wrapping [of the new building around the old one] was beautifully done: In muted color and crisp form, the new building, with facades on both 14th and F streets, is an appropriate frame for the original, allowing it to stand, in effect, as the hero on the corner." Unlike this sympathetic approach of 20 years ago, one suspects that if such an office addition were designed today, we would see glass curtain-walls on either side of this terracotta beauty. The high drama of the stark contrast probably would be pleasing to some, but ultimately it would be insensitive, isolating the original building and intensifying the fact that it is an artifact from a hundred years ago that has perchance been preserved. Fortunately, that didn't happen. Instead, the expanded Westory, as built, respects the ornate, original structure and incorporates it as an integral part of a very much still-thriving office block.

![]()

|

| (Author's collection.) |

The first decade of the 20th century saw a tremendous explosion of commercial real estate development in downtown Washington, and much of it was concentrated in the newly christened "financial" district along 14th and 15th Streets NW near the Treasury Building. Each new building, naturally, strove for attention through one form of superlative design or another. The Westory, completed in 1907, is an interesting case in point.

Before the Westory, the mansion of Dr. Robert King Stone stood on this site, as seen in the photograph above from the May 27, 1906, edition of the Washington Times. Stone's mansion was typical of the many stately brick residences that lined the streets of this neighborhood through most of the 19th century until larger commercial buildings gradually began to encroach in the 1870s. The Greek Revival house with its distinctive oval windows in the attic was built circa 1849 for Dr. Stone as a wedding gift from his wealthy father. Stone became perhaps the most prominent physician in Washington by the time he died in 1872. He had been President Lincoln's personal physician, and was summoned from his home here on the night of April 14, 1865, to attend to the mortally-wounded president at nearby Ford's Theater. After Dr. Stone's death, his widow remained in the house, refusing all offers to buy it and ignoring the rapid commercial changes that were engulfing the neighborhood around her. After her death in 1905, the property was finally sold, for an astonishing $76 per square foot, to developer George Higbee, who then immediately tore down the house and built the Westory in its place. In addition to the $190,000 he spent on the lot, Higbee probably put about $200,000 into constructing and decorating the new office building--a substantial investment at the time.

As the nine-story "skyscraper" neared completion in the summer of 1907, the Washington Post, with perhaps a slight bit of exaggeration, called it the "Flatiron's Rival," because it had been built on a narrow lot, as the famous New York landmark had been. The building, designed by Henry Jeckel of Boston, features elaborate white-glazed terracotta ornamentation (a new technique at the time), including a row of scowling lions atop the seventh floor and a massive cornice with ornamental wreaths and fleurs-de-lis that is probably too high for people to appreciate. At street-level are a series of massive two-story Ionic columns striped with distinctive rusticated bands. The lobby was originally finished in marble, mosaic, and bronze, with an elaborate stairway leading up to an equally lavish mezzanine level. Plate-glass windows, another very modern touch, allowed passersby to appreciate the interior decoration.

Commenting on the new building in November 1907, the Washington Times noted approvingly that the replacement of the old red-brick mansion of Dr. Stone with this tall, ornate, and thoroughly modern structure was a major step up for the neighborhood and that the new edifice beautifully complemented the Willard Hotel diagonally opposite. "The effect of this building upon values of realty in the neighborhood cannot be questioned," the Times proclaimed. The boom was on, and no end was in sight.

Of course, the building and its neighborhood have had theirs ups and downs since those heady days. The decline of downtown Washington in the 1960s and 1970s put old buildings such as the Westory in serious danger of demolition. In 1981, Don't Tear it Down, the historic preservation group that would later become the D.C Preservation League, surveyed downtown for buildings that did not have historic landmark protection but that deserved it--the Westory was on the list. While the building appears not to have officially gained historic status, developers got the message and made sure it was preserved.

An expansion of the building was designed by Shalom Baranes Associates and completed in 1990, winning an award for excellence by the American Institute of Architects in 1992. A second phase of the expansion was added in 2002. Benjamin Forgey, longtime architecture critic for the Evening Star and later the Washington Post, commented in 1993 on the building's addition: "The wrapping [of the new building around the old one] was beautifully done: In muted color and crisp form, the new building, with facades on both 14th and F streets, is an appropriate frame for the original, allowing it to stand, in effect, as the hero on the corner." Unlike this sympathetic approach of 20 years ago, one suspects that if such an office addition were designed today, we would see glass curtain-walls on either side of this terracotta beauty. The high drama of the stark contrast probably would be pleasing to some, but ultimately it would be insensitive, isolating the original building and intensifying the fact that it is an artifact from a hundred years ago that has perchance been preserved. Fortunately, that didn't happen. Instead, the expanded Westory, as built, respects the ornate, original structure and incorporates it as an integral part of a very much still-thriving office block.

I love the wroght iron balcony at the second floor of Stone's mansion. I don't know it it's because of DC's predominantly southern culture before the Civil War, but it's definatley cool. Keep it coming!

ReplyDeleteI agree that like an obnoxious dinner guest, now-a-days the infilling architect wouldn't have the table manners this original Shalome design projects. I really thought we'd turned the corner with contextualism, and a return to urban civility when it came to architecture in the 90's. Oh well!

ReplyDeleteagreed. i am not a fan of setting of historic architecture by making the surrounding new work as different as possible. sometimes, replicating what is tasteful and well done is a good thing!

ReplyDelete