There’s a charming little National Park Service site at 3051 M Street in Georgetown, known as the

Old Stone House. It may be the oldest surviving structure in the District of Columbia, dating to 1765, when a certain Christopher Layman built it as a carpenter’s shop and living quarters. Solidly built in the “Pennsylvanian” vernacular style, the little building looks hopelessly out of place on bustling modern-day M Street. Why, then, has it been preserved when all else seemingly was lost, and why has it been taken over by the Park Service? What momentous historical personage or event is connected with it? The answer: nothing. Not a blessed thing of any historical significance ever, as far as we know, happened in this house. It’s just a really old and fascinating little house. That’s the only reason it’s a national historic site.

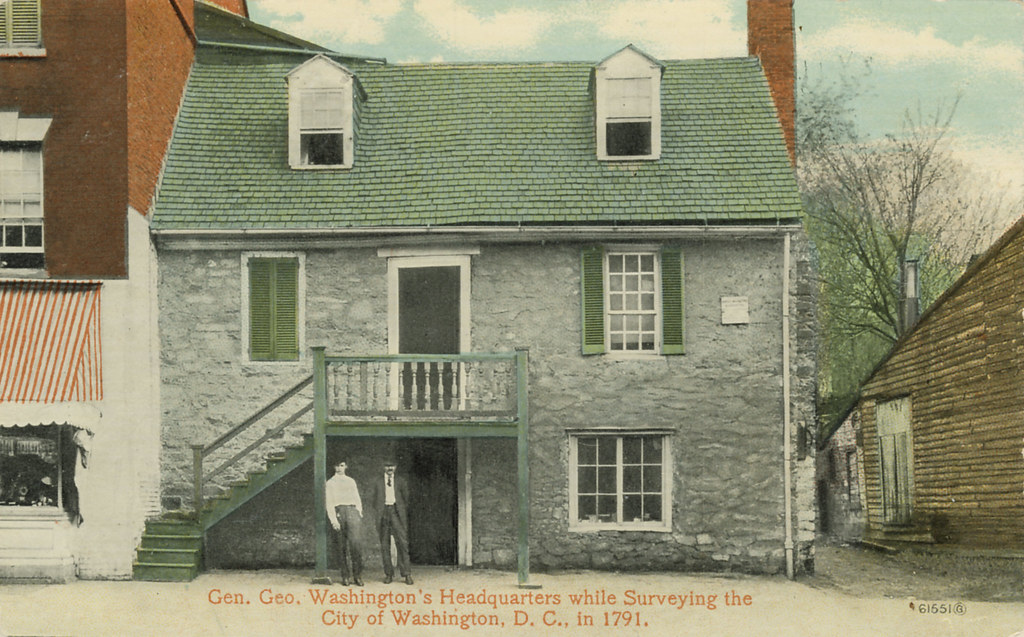

|

| (Author's collection). |

At this point you may be feeling like you’re missing some important part of this story—and then you look at this postcard of the house from around 1910, and you see the clearly-stated caption: “Gen. Geo. Washington’s Headquarters while Surveying the City of Washington, D.C. in 1791.” Is that true?

Well, George Washington did indeed stop in Georgetown for a few days in 1791 to settle the arrangements for the new Federal city that would be named after him. He met with landowners, surveyors, and his newly-designated city planner, Peter L’Enfant, to make necessary arrangements and get the ball rolling. Subsequently L’Enfant also had an “office” in Georgetown as he laid out his acclaimed grid of streets crisscrossed by grand diagonal avenues. The three commissioners for the new city, charged with administering early road and building construction efforts, likewise worked from Georgetown.

In those days the place for travelers to meet people, do business, and obtain lodging was more than likely to be a tavern house, and Georgetown’s most famous tavern, where everybody stopped, was Suter’s Tavern, opened by John Suter in 1783 and known officially as the Fountain Inn. It seems that any important business done in Georgetown was conducted there, from all the planning work for Washington City to Georgetown’s own municipal meetings. George Washington was hardly unique in stopping there. Thomas Jefferson once stated that “no man on the Atlantic coast can bring out a better bottle of Madeira or Sherry than old Suter.”

Now, nobody ever recorded street addresses in those days—there simply was no need—and because Suter didn’t actually own the property that he used for his tavern, there isn’t any deed of sale that would definitively specify the tavern’s location. –So, many decades later, it was no longer clear where Suter's Tavern was actually located. Why people began to think that the Old Stone House was Suter’s Tavern is equally unclear. Perhaps the story about Washington using the Old Stone House as his headquarters developed on its own, regardless of what was known about Suter’s.

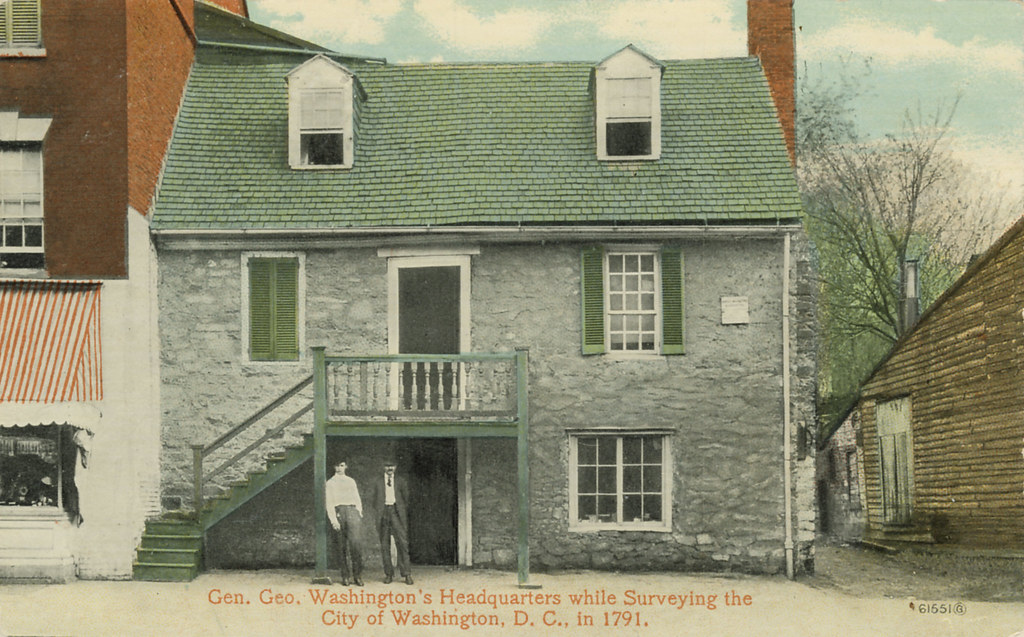

|

| Another early 1900s postcard of the Old Stone House (Author's collection). |

In December 1902, the

Washington Times reported that there was “a tradition that schoolchildren playing in the attic of this little building many years ago found some drawings and plans which seemed to have some relation to the early plans of the city.” Maybe that thin shred was what led someone—supposedly with the support of contributions from schoolchildren—to put the first of a series of markers on the house claiming that it was Washington’s "headquarters" (You can see a marker up on the right hand side of the house in the postcard views). Such a marker seems to have been there as early as the 1870s. However, the

Washington Times author quickly notes that “on the other hand we are informed that there is no authentic history which points to any occupancy of this house by President Washington on any occasion,” so the doubts about the story seem to go back nearly as far as the story itself.

Nevertheless, Georgetowners liked the little stone house and the idea that it was “Washington’s Headquarters,” and it seems there wasn’t much concern about getting to the truth of the matter. Postcards like these were produced, and intermittent efforts were made to preserve the place. A bill was introduced in Congress in 1929 to make “Washington’s Engineering Headquarters” a national monument with an engineering theme. But local historians came out against the idea. Allen C. Clark, president of the Columbia Historical Society, stated “the face of the Old Stone House has been a haven of historical markers. These have been false in their message.” The bill was not enacted, and that was that—at least until Ms. Bessie Wilmarth Gahn joined the fray in 1940.

Gahn seems to have made the most ambitious attempt on record to claim that the Old Stone House was Suter’s Tavern. She wrote a whole book on

George Washington’s Headquarters in Georgetown, in which she provided very detailed research showing that Washington had made Suter’s Tavern his headquarters in Georgetown (true enough) and, because John Suter’s son had a connection to the Old Stone House, that it must have been Suter’s Tavern (not true at all). Despite gaining a lot of attention at the time, Gahn’s analysis left many in doubt.

So where was Suter’s Tavern, really? National Park Service historian Cornelius W. Heine wrote what seemed to be a

definitive study of the Old Stone House in 1955, after it had been acquired by the government. In it he presented with great fanfare his research into what he called “Washington’s Most Unusual Mystery”—the location of Suter’s Tavern—a “seemingly insoluble mystery” that “has intrigued and baffled local historians to this very time.” He went on provide fairly convincing evidence that the tavern had been located down on K Street, on its northwest corner with 31st Street. Central to his analysis was his discovery at the Library of Congress of “a certain unusual photograph…among an old miscellaneous collection.” Heine found that “When the photograph was turned over, there on the back, in old but bold penmanship were the words “Suter’s Tavern.” The mystery was solved!

Or was it? Many people thought that the case was closed at that point. The

Post reported in September 1955 that the site of Suter's Tavern had finally been pinpointed, quoting National Park Service director Conrad L. Wirth as saying that the facts gathered by Heine "prove conclusively" that the site of the tavern had been found. The Georgetown Citizens Association approved erection of an historical marker, and one was soon in place at the site, which by that time was an empty corner of a block owned by the D.C. government, on which the Georgetown incinerator was also located. Not everyone was convinced the mystery had really been solved, however. As Bessie Gahn had observed, the site on K Street was not likely even habitable in 1791, when marshes on the edge of the Potomac probably were still there. Others had said Suter's Tavern was elsewhere, notably Christian Hines (1781-1874), a prominent early Georgetown resident, who in his

Early Recollections of Washington City, had located Suter's on Bridge Street (now Wisconsin Avenue) just north of where it is now crossed by the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.

Before the D.C. government sold the old incinerator property for redevelopment, it commissioned the firm of Garrow and Associates, Inc., to do an archeological investigation of the 31st and K Street site in 1986 to try to determine through direct physical evidence whether the claim that it was the location of Suter's Tavern was plausible. It turned out not to be. The archaeologists determined from remains found on the site that it was not inhabited prior to approximately 1810 at the earliest, and that there were several layers of earthen fill deposited there, on which all later structures had been built. So this theory, along with the Old Stone House theory, was shot down, and we may never know for sure where this incredibly important building was located.

|

| The Old Stone House as it appears today (photo by the author). |

But let's go back to the Old Stone House, because it was this charming little building that everyone wanted to save. Christopher Layman died shortly after the house was built, and his widow sold it to one Cassandra Chew. One of Mrs. Chew's daughters, Mary Smith, was living in the Old Stone House at the time that George Washington and Pierre L'Enfant were staying at Suter's, somewhere nearby. Beginning in 1800, John Suter, Jr., son of the proprietor of Suter's Tavern, rented the Old Stone House and set up his clockmaker's shop in the basement commercial space there. In fact one of his tall-case clocks is on display now at the restored building. Subsequent occupants used the house for a tailor's shop, a house painter's shop, and an antiques store.

|

| The dining room, with one of John Suter's tall case clocks on display (photo by the author). |

By 1950, it didn’t matter anymore whether Washington or L’Enfant or anybody else had ever done anything important there—it was a wonderful old house, and it was threatened by the commercial expansion of Georgetown. Grimy, commercial Georgetown was on the cusp of a new trend toward gentrification, and a number of historic buildings still survived, although many were threatened. Plans had been announced to tear down the Old Stone House and replace it with a modern commercial building. The Georgetown Citizens Association, which envisioned a “Williamsburg” along M Street of restored or recreated historic buildings, pushed to have the federal government acquire the Old Stone House for the Park Service, which restored it in the late 1950s. Meanwhile, Georgetown became fashionable once again, and M Street and Wisconsin Avenue turned into prime sites for expensive shops and galleries. The K Street area would take a lot longer to come back, and, well, the real Suter’s Tavern was lost anyway, wherever it had been. —Oh, and that marker that had been set in the ground on the corner of 31st and K Streets? After the property was redeveloped, the marker was lost too. So just use your imagination.

|

| The front parlor or bedroom (photo by the author). |

John,

ReplyDeleteWonderful blog entry. Thanks for writing this! A copy will go into the Peabody Room collection.

Jerry

Jerry, thank you for the kind words and for your invaluable assistance!

ReplyDeleteJohn,

ReplyDeleteThis is a very interesting and informative blog. I look forward to reading through your posts. You can definitely turn this blog into a book!

I was wondering about that little house!

p.s. I am adding you to my blog list!

-- Vicki

What a wonderful piece to read. Thank you for writing it.

ReplyDeleteThe first two photos are created from the same original photo, with the same two men standing in the same position. Even the warp in the bottom of the roofline is the same. It appears the first one is a retouched, partly colorized version of the second one (the postcard), with the signs removed. They are cropped a bit differently, as well. Interesting!

ReplyDelete