Lost Opportunities: The Key Mansion Saga

In a breezy May 1981 article entitled, “The Case of the Lost Landmark,” the Washington Post relished what it took to be a highly amusing case of bureaucratic bungling. “Misplacing a house key is one thing,” the article intoned, “Misplacing a Key house is quite another.” In interviews with officials from the National Park Service, the Post’s reporter found that the home of Francis Scott Key, writer of the Star-Spangled Banner, which used to stand on M Street in Georgetown close to the Key Bridge, was torn down in 1947 and its parts saved for possible reconstruction later. However, it seems that the Park Service had misplaced these parts and in 1981 could no longer find them. –Oops!

The real story of what happened to the house and how it was almost saved several times is much more complicated and offers much richer lessons about how not to pursue historic preservation.

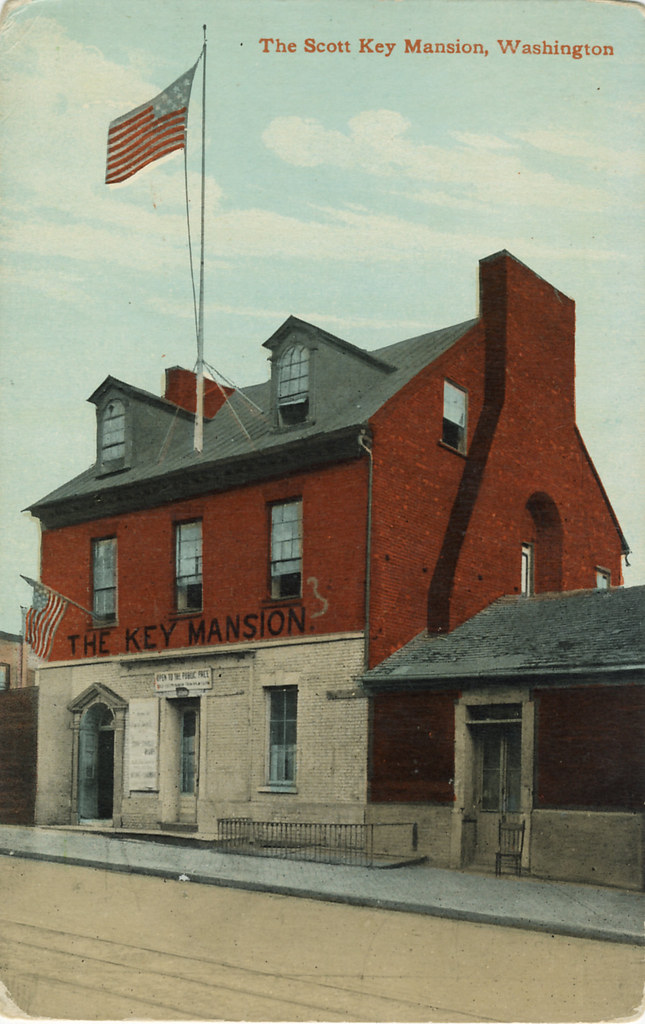

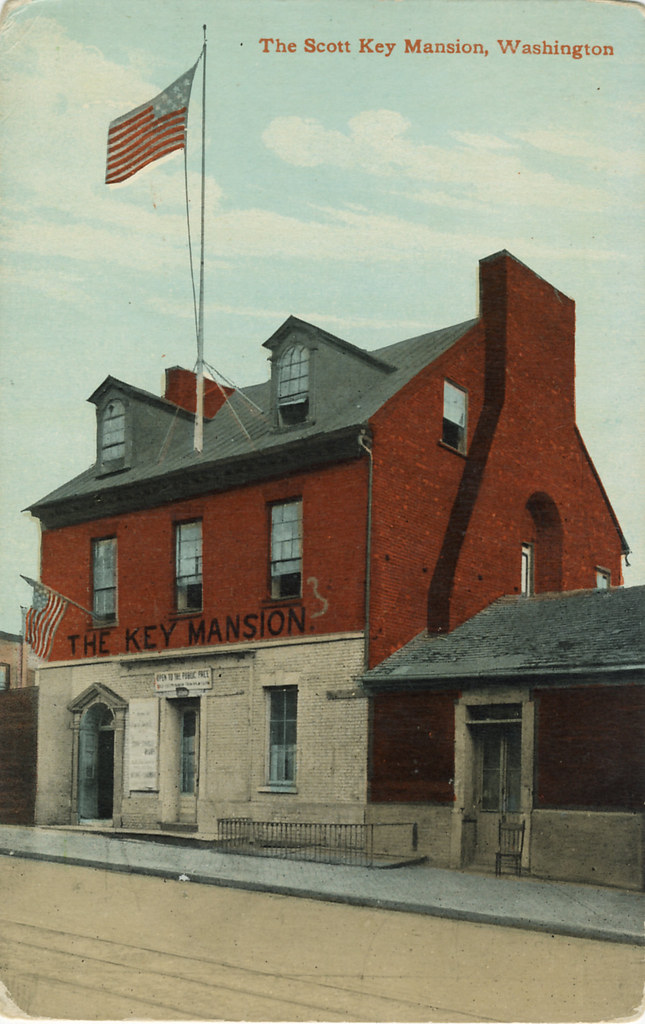

![]() The house, seen in this postcard from about 1909, was originally built by a merchant named Thomas Clark in 1795, long before any bridges or the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal disrupted the local landscape. In those days, terraced gardens sloped down gracefully behind the house to the Potomac River. Francis Scott Key leased the house in late 1805 and was residing there in 1814, when he went on his mission of mercy to Baltimore to secure the release of Dr. William Beanes from the British. While detained on a British ship in Baltimore Harbor during the siege of Fort McHenry, he penned what would become our national anthem.

The house, seen in this postcard from about 1909, was originally built by a merchant named Thomas Clark in 1795, long before any bridges or the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal disrupted the local landscape. In those days, terraced gardens sloped down gracefully behind the house to the Potomac River. Francis Scott Key leased the house in late 1805 and was residing there in 1814, when he went on his mission of mercy to Baltimore to secure the release of Dr. William Beanes from the British. While detained on a British ship in Baltimore Harbor during the siege of Fort McHenry, he penned what would become our national anthem.

In about 1830, Key and his family moved out of the Georgetown house for a place nearer Judiciary Square in Washington City, where he was District Attorney. It is said that the cutting of the C&O Canal directly through his backyard, and the resulting boat traffic, had greatly reduced the desirability of the place as a residence.

![]()

The neighborhood seems to have gone downhill from that point forward. By the end of the 19th century, the lower parts of Georgetown were a messy, industrial area. Georgetown’s days as a thriving tobacco port had long gone; the harbor had silted up, and seagoing vessels could no longer dock there. What remained were grimy factories and mills. The Key Mansion by the 1890s was being used as a commercial shop rather than a residence.

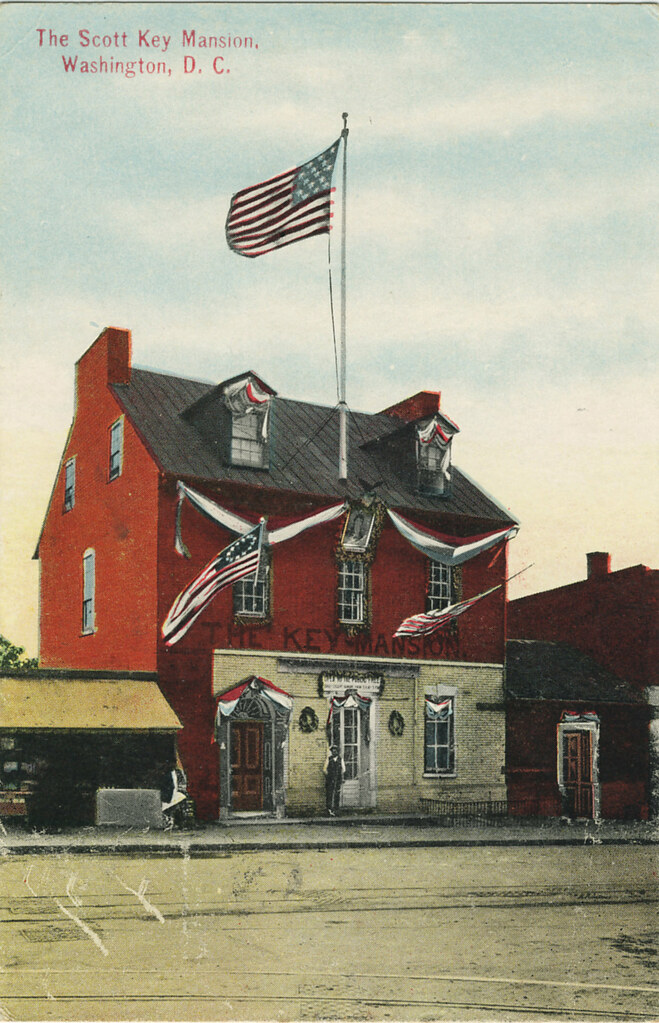

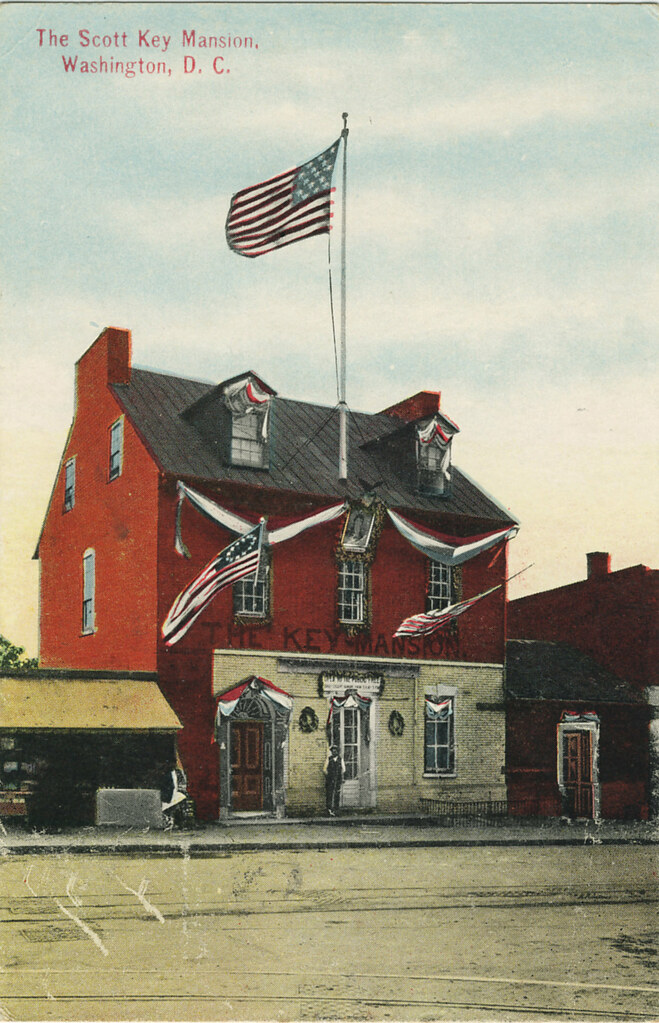

Then, in 1907, a group of prominent individuals led by Admiral George Dewey organized a group to try to save the Key Mansion as a memorial to the author of the Star-Spangled Banner. They leased the house, festooned it with flags and a large portrait of Key, and opened it as a museum on Flag Day in 1908. This postcard shows how the house looked at that time.

![]()

The group set a goal of raising $15,000 to purchase the house and operate it as a permanent museum. Others had made a similar move to save the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia in 1898; why not do the same thing with the Francis Scott Key House?

Unfortunately, this well-meaning effort was doomed from the start. The Key Mansion was located at the far end of Georgetown’s then-tawdry commercial strip, and tourists didn’t necessarily want to go there. Plus, the drab-looking building was empty—no historic furnishings; nothing really to see. Elaborate membership certificates were produced, to be bestowed on those who would contribute a dime or a quarter. It didn’t work. The museum soon closed.

The real death blow came shortly thereafter, in 1912 or 1913, when drastic modifications were made to the structure. The entire gabled top floor was removed and replaced with a flat roof. The distinctive split chimney on the side of the house was also removed, as was Key’s office, which had been an addition on the side of the house. Finally, the entire façade of the building was removed and replaced with new brick and large plate-glass commercial windows. At this point you couldn’t tell it was the Key House anymore; it looked like any other commercial storefront. It was so unrecognizable that many people thought the house had been torn down.

The house, in fact, was still there after the bridge was built in 1923, but its days were numbered. The government acquired the properties in the block along M Street north of the bridge in 1931 as part of a new Palisades Park. Then people started talking about saving the house again—or rather reconstructing it. By 1935, the Park Service had developed plans to do just that, using what few original elements remained. When approval came in 1941 to build a ramp to the new Whitehurst Freeway through the site of the house, it was time for a final decision to be made.

The prevailing opinion at that time among many leading Washingtonians was that the Key House should be preserved in some fashion. The Columbia Historical Society published a pamphlet in 1947 urging it be preserved, restored, and turned over to them to use as their headquarters. This was probably asking too much, but Congress did pass a bill to fund construction of a replica of the Key House on the other side of Key Bridge, using the remaining original elements of the house, after the new Whitehurst Freeway was constructed. Following that plan, contractors dismantled the house, numbered the original bricks and foundation stones, and placed them on the site just south of the bridge where the replica building was supposed to be constructed.

But a new wrinkle emerged at this point. The Bureau of the Budget objected to the bill on the grounds that the replica house would cost too much to build and maintain—and besides, it would just be a replica, not the real thing. President Harry Truman took this advice and pocket-vetoed the bill in 1948 that would have funded construction of the replica house.

Thus, what the Park Service really lost was that pile of numbered bricks and foundation stones, which suddenly had no purpose after the scheme for the replica house went unfunded. It’s true that no one knows exactly how they disappeared over the years, but presumably they would have made useful materials for rehabilitating other old houses in Georgetown. One theory is that the Park Service itself used at least some of the material when it restored the Old Stone House up at 3051 M Street in 1957.

—So is it the Park Service’s fault that the Key Mansion was lost? –Seems to me the real opportunity to save the house was lost in 1908, when public apathy conspired with an ill-conceived house-museum plan to doom the Key Mansion to oblivion.

![]()

By the time this postcard was issued in the 1930s, the Key Mansion looked nothing like the way it is shown here.

By the time this postcard was issued in the 1930s, the Key Mansion looked nothing like the way it is shown here.

The real story of what happened to the house and how it was almost saved several times is much more complicated and offers much richer lessons about how not to pursue historic preservation.

In about 1830, Key and his family moved out of the Georgetown house for a place nearer Judiciary Square in Washington City, where he was District Attorney. It is said that the cutting of the C&O Canal directly through his backyard, and the resulting boat traffic, had greatly reduced the desirability of the place as a residence.

|

| A view of the mansion in the late 19th century (Author's collection). |

The neighborhood seems to have gone downhill from that point forward. By the end of the 19th century, the lower parts of Georgetown were a messy, industrial area. Georgetown’s days as a thriving tobacco port had long gone; the harbor had silted up, and seagoing vessels could no longer dock there. What remained were grimy factories and mills. The Key Mansion by the 1890s was being used as a commercial shop rather than a residence.

Then, in 1907, a group of prominent individuals led by Admiral George Dewey organized a group to try to save the Key Mansion as a memorial to the author of the Star-Spangled Banner. They leased the house, festooned it with flags and a large portrait of Key, and opened it as a museum on Flag Day in 1908. This postcard shows how the house looked at that time.

The group set a goal of raising $15,000 to purchase the house and operate it as a permanent museum. Others had made a similar move to save the Betsy Ross House in Philadelphia in 1898; why not do the same thing with the Francis Scott Key House?

Unfortunately, this well-meaning effort was doomed from the start. The Key Mansion was located at the far end of Georgetown’s then-tawdry commercial strip, and tourists didn’t necessarily want to go there. Plus, the drab-looking building was empty—no historic furnishings; nothing really to see. Elaborate membership certificates were produced, to be bestowed on those who would contribute a dime or a quarter. It didn’t work. The museum soon closed.

|

| Tourists pose in front of the Key Mansion, circa 1908 (author's collection). |

|

| The Key Mansion in 1931 (Author's collection). |

The prevailing opinion at that time among many leading Washingtonians was that the Key House should be preserved in some fashion. The Columbia Historical Society published a pamphlet in 1947 urging it be preserved, restored, and turned over to them to use as their headquarters. This was probably asking too much, but Congress did pass a bill to fund construction of a replica of the Key House on the other side of Key Bridge, using the remaining original elements of the house, after the new Whitehurst Freeway was constructed. Following that plan, contractors dismantled the house, numbered the original bricks and foundation stones, and placed them on the site just south of the bridge where the replica building was supposed to be constructed.

But a new wrinkle emerged at this point. The Bureau of the Budget objected to the bill on the grounds that the replica house would cost too much to build and maintain—and besides, it would just be a replica, not the real thing. President Harry Truman took this advice and pocket-vetoed the bill in 1948 that would have funded construction of the replica house.

Thus, what the Park Service really lost was that pile of numbered bricks and foundation stones, which suddenly had no purpose after the scheme for the replica house went unfunded. It’s true that no one knows exactly how they disappeared over the years, but presumably they would have made useful materials for rehabilitating other old houses in Georgetown. One theory is that the Park Service itself used at least some of the material when it restored the Old Stone House up at 3051 M Street in 1957.

—So is it the Park Service’s fault that the Key Mansion was lost? –Seems to me the real opportunity to save the house was lost in 1908, when public apathy conspired with an ill-conceived house-museum plan to doom the Key Mansion to oblivion.

By the time this postcard was issued in the 1930s, the Key Mansion looked nothing like the way it is shown here.

By the time this postcard was issued in the 1930s, the Key Mansion looked nothing like the way it is shown here.

If anyone has an authentic piece of the Key House that they would like to donate to the Georgetown Neighborhood Library's Peabody Room in honor of its 75th anniversary reopening this October, please contact me!

ReplyDeleteJerry A. McCoy

Special Collections Librarian

Peabody Room

202.727.1213

jerry.mccoy@dc.gov

Thank you for sharing this. It is sad to see so many historic places go.

ReplyDelete